Fifty-eight years after African leaders rejected Ghanaian president Kwame Nkrumah’s radical African-union project, Europeans, via the European Union, have implemented all the nine proposals Nkrumah made in 1963, including a common currency and the ability for citizens to cross borders without a passport. At home in Africa, however, it has been more talk than action: Almost all the things Nkrumah proposed in May 1963 remain unachieved. In this wide-ranging piece, Baffour Ankomah takes us through the harrowing story of Africa since then and compares it to a triumphant Europe in charge of its own destiny.

Comparing what Africa has done since the founding of the Organization of African Unity (OAU) in 1963, which morphed into the African Union (AU) in 2002, with the long progressive journey that the European Union (EU) has taken to develop institutions and policies that have bettered the lives of its member states and people, it makes Africa look like a continent of lip service, a people who enjoy empty talk at the expense of concrete action.

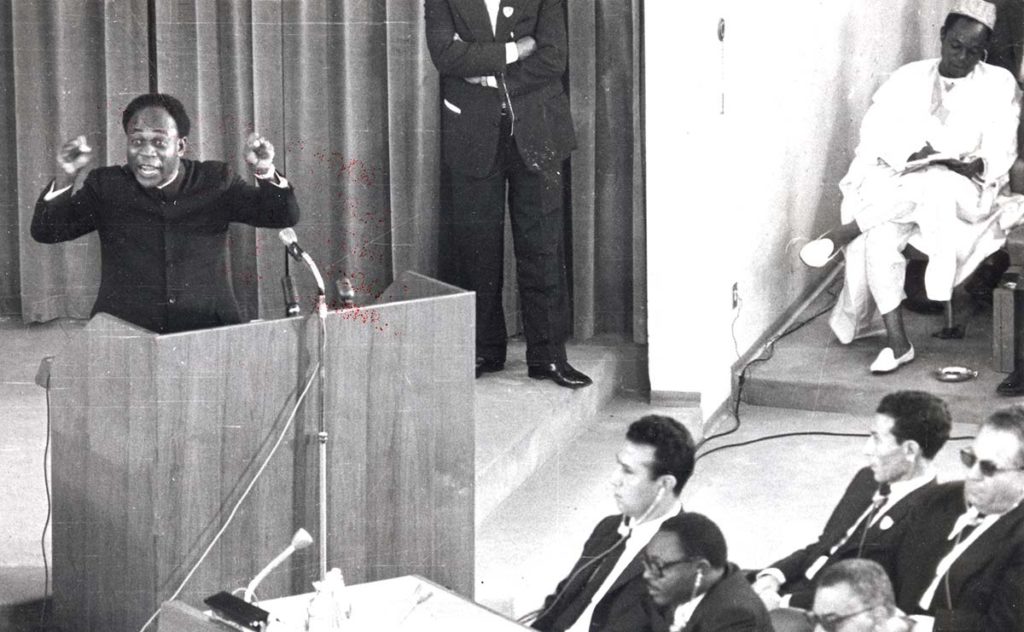

It might have turned out differently. Kwame Nkrumah, then Ghana’s president, was an eloquent advocate for uniting Africa in much the same way as the EU would later unite Europe. On May 24, 1963, as leaders and top officials of 32 independent African countries met in the Ethiopian capital, Addis Ababa, to find ways to unite the continent, Nkrumah gave one of the greatest speeches of his life, a speech that has since become the definitive blueprint for a strong African unity – a unity that, sadly, has remained elusive.

There was a sharp division in African ranks on the question, which found expression in three main groups of nations: the Brazzaville Group; the Monrovia Group (led by the Liberian President William V.S. Tubman); and the Casablanca Bloc, led by Nkrumah and President Gamal Abdel Nasser of Egypt. Each of the three groups was determined to pull its own way, thus killing any hope of a joint action.

The Brazzaville Group consisted of 12 countries: Congo Brazzaville, Cameroon, Cote d’Ivoire, Dahomey (later Benin), Gabon, Upper Volta (later Burkina Faso), Madagascar, Mauritania, Niger, Central African Republic, Senegal, and Chad. They had founded the African and Malagasy Union in 1960.

At best, the Monrovia Group, which amalgamated the 12 countries of the Brazzaville Group with eight others – Liberia, Nigeria, Ethiopia, Sierra Leone, Somalia, Togo, Tunisia, and Congo Leopoldville (now Kinshasa) – wanted a gradual or staggered unity process for Africa. At worst, they were highly averse to any African unity at all, as they believed that Africa’s independent states should cooperate and exist in harmony, but without the political federation and deep economic integration advocated by Nkrumah and his friends.

The Casablanca Bloc, which emerged in 1961, was all for a strong African union. It comprised seven states: Ghana, Guinea, Mali, Libya, Algeria, Egypt, and Morocco.

Meanwhile, the United Kingdom had been scheming behind the scenes to get the leading lights of Africa, particularly Presidents Julius Nyerere of Tanzania and Abubakar Tafawa Balewa of Nigeria, to scupper Nkrumah’s plans to set up a government and economic system that would include all of Africa. The United States, for its part, was using its influence on Liberia and President Tubman to get him and other African leaders to stop Nkrumah’s push for an African union.

This was the unhealthy and charged situation as the African-unity conference opened on May 24, 1963. But Nkrumah refused to be intimidated by the prevailing animosity.

‘We must unite or sink’

In a historic speech to the 32 assembled African leaders – the presidents of 30 countries and representatives from two others – Nkrumah did everything but cry to encourage them, leading their countries’ emergence from almost a century of colonial rule, to come together to create “a union of independent African states.” That, he said, would give Africa a powerful voice in the world and a secure base upon which a continental economy and well-being would be built.

Nkrumah yearned for a strong African union, knowing that without it, Africa had no hope of achieving economic prosperity and political stability. “Our objective is African union now,” he said in the first paragraph of his speech. “There is no time to waste. We must unite now or perish. I am confident that by our concerted effort and determination, we shall lay here the foundations for a continental Union of African States.”

The Monrovia Group’s skepticism about a continental union was wrong, Nkrumah argued, because imperialism had become “stronger, more ruthless and experienced, and more dangerous in its international associations,” and Africa needed to avoid merely exchanging colonial rule for neo-colonialist domination.

“On this continent, it has not taken us long to discover that the struggle against colonialism does not end with the attainment of national independence,” he declared. “Independence is only the prelude to a new and more involved struggle for the right to conduct our own economic and social affairs; to construct our society according to our aspirations, unhampered by crushing and humiliating neo-colonialist controls and interference.

The assembled leaders had “bent all our strength” to attain political independence, he went on; now, he said, “we must recognize that our economic independence resides in our African union and requires the same concentration” and “the social and economic development of Africa will come only within the political kingdom, not the other way around.”

Africa’s resources irrigated the whole system of the Western economy, Nkrumah said. “Africa provides more than 60% of the world’s gold,” he told the leaders. “A great deal of the uranium for nuclear power, of copper for electronics, of titanium for supersonic projectiles, of iron and steel for heavy industries, of other minerals and raw materials for lighter industries – the basic economic might of the foreign powers – comes from our continent. Experts have estimated that the Congo Basin alone can produce enough food crops to satisfy the requirements of nearly half the population of the whole world.

“And here we sit talking about gradualism, talking about step by step. Are you afraid to tackle the bull by the horn?” he asked the leaders.

Only by uniting the continent economically could Africans achieve enough prosperity to control their own destiny, Nkrumah continued.

“With capital controlled by our own banks, harnessed to our own true industrial and agricultural development, we shall make our advance,” he said. “We shall accumulate machinery and establish steel works, iron foundries and factories; we shall link the various states of our continent with communications by land, sea, and air. We shall cable from one place to another, phone from one place to the other, and astound the world with our hydro- electric power. We shall drain marshes and swamps, clear infested areas, feed the undernourished, and rid our people of parasites and disease.”

Ten years before, Nkrumah said, these would have been “the fantasies of an idle dreamer. But this is the age in which science has transcended the limits of the material world, and technology has invaded the silences of nature. The world is no longer moving through bush paths or on camels and donkeys.

“It is within the possibility of science and technology to make even the Sahara Desert bloom into a vast field with verdant vegetation for agricultural and industrial development. We shall harness the radio, television, and giant printing presses to lift our people from the dark recesses of illiteracy.

“We cannot afford to pace our needs, our development, our security, to the gait of camels and donkeys. We cannot afford not to cut down the overgrown bush of outmoded attitudes that obstruct our path to the modern open road of the widest and earliest achievement of economic independence and the raising up of the lives of our people to the highest level.”

Only a united Africa functioning under a union government, Nkrumah insisted, would have the material and moral resources to give adequate assistance to states trying to improve the economic and social conditions of our people.

“Unite we must,” he insisted. “Without necessarily sacrificing our sovereignties, big or small, we can here and now forge a political union based on defense, foreign affairs and diplomacy, and a common citizenship, an African currency, an African monetary zone, and an African central bank. We must unite in order to achieve the full liberation of our continent. We need a common defense system with African high command to ensure the stability and security of Africa.

“We need unified economic planning for Africa. Until the economic power of Africa is in our hands, the masses can have no real concern and no real interest for safeguarding our security, for ensuring the stability of our regimes, and for bending their strength to the fulfilment of our ends.

“With our united resources, energies and talents we have the means, as soon as we show the will, to transform the economic structures of our individual states from poverty to that of wealth, from inequality to the satisfaction of popular needs. Only on a continental basis shall we be able to plan the proper utilization of all our resources for the full development of our continent.”

A common currency

Having a common currency would be crucial, Nkrumah argued, sometimes raising his voice, sometimes lowering it, sometimes pounding the table.

“How else will we retain our own capital for own development?” he asked his fellow leaders. “How else will we establish an internal market for our own industries? By belonging to different economic zones, how will we break down the currency and trading barriers between African states, and how will the economically stronger amongst us be able to assist the weaker and less developed states?”

Having a currency system backed by the resources of a foreign state, Nkrumah continued, inevitably meant being subject to the trade and financial arrangements of that foreign country. And the multiple customs and currency barriers created by the colonial division of Africa have “served to widen the gap between us,” he added.

“How, for example, can related communities and families trade with, and support one another successfully, if they find themselves divided by national boundaries and currency restrictions?” he asked. “The only alternative open to them in these circumstances is to use smuggled currency and enrich national and international racketeers and crooks who prey upon our financial and economic difficulties.”

To open the eyes of the assembled African leaders, he told them: “No independent African state today by itself has a chance to follow an independent course of economic development, and many of us who have tried to do this have been almost ruined or have had to return to the fold of the former colonial rulers. This position will not change unless we have a unified policy working at the continental level.

“Is it not unity alone that can weld us into an effective force, capable of creating our own progress and making our valuable contribution to world peace? Which independent

African state, which of you here, will claim that its financial structure and banking institutions are fully harnessed to its national development?

“Which will claim that its material resources and human energies are available for its own national aspirations? Which will disclaim a substantial measure of disappointment and disillusionment in its agricultural and urban development?”

The Ghanaian president advocated that the first step towards an African cohesive economy would be a unified monetary zone, with, initially, an agreed common parity for African national currencies. To facilitate this arrangement, he offered that Ghana would change to a decimal system, replacing one derived from the British system of pounds, shillings, and pence. When that was working successfully, “there would seem to be no reason for not instituting one common currency and a single bank of issue,” Nkrumah said.

A common defense system

Once Africa had assured its stability by a common defense system and orientated its economy beyond foreign control by a common currency, Nkrumah explained, it could “begin to ascertain whether in reality we are the richest, and not, as we have been taught to believe, the poorest among the continents. We can determine whether we possess the largest potential in hydroelectric power, and whether we can harness it and other sources of energy to our industries. We can proceed to plan our industrialization on a continental scale, and to build up a common market for nearly 300 million people. Common continental planning for the industrial and agricultural development of Africa is a vital necessity!”

Nkrumah concluded that section of the speech by saying: “So many blessings flow from our unity; so many disasters must follow on our continued disunity. The hour of history which has brought us to this assembly is a revolutionary hour. It is the hour of decision.

“The masses of the people of Africa are crying for unity. The people of Africa call for the breaking down of the boundaries that keep them apart. They demand an end to the border disputes between sister African states – disputes that arise out of the artificial barriers raised by colonialism. It was colonialism’s purpose that divided us. It was colonialism’s purpose that left us with our border irredentism, that rejected our ethnic and cultural fusion.”

Gradualism

Nkrumah then turned to the issue of “gradualism,” the hallmark of his opponents’ arguments.

“It has been suggested that our approach to unity should be gradual, that it should go piecemeal,” he said. “This point of view conceives of Africa as a static entity with ‘frozen’ problems which can be eliminated one by one and when all have been cleared then we can come together and say: ‘Now all is well, let us now unite.’

“This view takes no account of the impact of external pressures. Nor does it take cognizance of the danger that delay can deepen our isolations and exclusiveness; that it can enlarge our differences and set us drifting further and further apart into the net of neocolonialism, so that our union will become nothing but a fading hope, and the great design of Africa’s full redemption will be lost, perhaps, forever.”

The view that Africa’s difficulties could be resolved simply through greater collaboration between nations greatly troubled Nkrumah.

“This way of looking at our problems denies a proper conception of their inter- relationship and mutuality,” he said. “It denies faith in a future for African advancement in African independence. It betrays a sense of solution only in continued reliance upon external sources through bilateral agreements for economic and other forms of aid.

“The fact is that although we have been cooperating and associating with one another in various fields of common endeavor even before colonial times, this has not given us the continental identity and the political and economic force which would help us to deal effectively with the complicated problems confronting us in Africa today.”

Wanted: A united Africa

Nkrumah asked rhetorically about several possible models for an African union. Should it be like the United Nations, “whose decisions are framed on the basis of resolutions that in our experience have sometimes been ignored by member states, where groupings are formed and pressures develop in accordance with the interest of the groups concerned?” Or like the Organization of American States, “in which the weaker states within it can be at the mercy of the stronger or more powerful ones politically or economically, and all at the mercy of some powerful outside nation or group of nations?”

The Ghanaian president then called for an end to the small political groupings and regional blocs on the continent.

“If we succeed in establishing a new set of principles as the basis of a new charter of stature for the establishment of a continental unity of Africa, and the creation of social and political progress for our people, then in my view, this conference should mark the end of our various groupings and regional blocs,” he said.

“But if we fail and let this grand and historic opportunity slip by, then we shall give way to greater dissension and division among us for which the people of Africa will never forgive us. And the popular and progressive forces and movements within Africa will condemn us. I am sure therefore that we shall not fail them.”

The blueprint

The first step, Nkrumah said, should be a declaration of common principles, laying the foundations of unity. The second would be setting up an “All-Africa Committee of Foreign Ministers” to establish a permanent body of officials and experts to work out the structure and functions of machinery for the union government. He suggested that putting the union’s headquarters or capital in a central place in Africa, such as Bangui in the Central African Republic or Leopoldville [now Kinshasa] in Congo, might be the fairest suggestion.

The Committee of Foreign Ministers, officials and experts, he said, should be empowered to establish:

(1) A commission to frame a constitution for a Union Government of African States.

(2) A commission to work out a continent-wide plan for a unified or common economic and industrial program for Africa; including a common market for Africa; an African currency, monetary zone, and central bank; a continental communication system; and three separate commissions to draw up details for a common foreign policy and diplomacy, produce plans for a common system of defense, and make proposals for a common African citizenship.

At the time, Nkrumah’s proposals were radical. The future European Union, then 12 years old, included only six countries, each with separate national currencies. If the African leaders had accepted Nkrumah’s ideas, they would have made Africa one of the most progressive blocs in the world. But most of the leaders, some encouraged or swayed by the influence of foreign powers, had different ideas.

The Monrovia Group, consisting of 20 of the 32 African states, was implacable. The pro-union Casablanca Bloc had only seven members. The other five independent African countries at the time – Tanganyika (now Tanzania), Kenya, Rwanda, Uganda, and Sudan – were more inclined to the views of the Monrovia Group, except perhaps Uganda.

The UK was discreetly backing President Julius Nyerere of Tanganyika and Nigeria’s Tafawa Balewa to reject Nkrumah’s “union government of African states” idea. Their view carried the day. So, despite all the frenetic energy and passion Nkrumah displayed on the podium, the next day, the 32 African nations assembled in Addis Ababa settled for a loose and weak Organization of African Unity (OAU). They signed its charter the same day, May 25, 1963.

The countries that signed the charter were: Algeria, Burundi, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Congo (Brazzaville, now Republic of the Congo), Congo (Kinshasa, now Democratic Republic of the Congo), Dahomey (now Benin), Cote d’Ivoire, Ethiopia, Gabon, Ghana, Guinea, Liberia, Libya, Madagascar, Mali, Mauritania, Morocco, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Somalia, Sudan, Tanganyika (now Tanzania), Togo, Tunisia, Uganda, United Arab Republic (Egypt), and Upper Volta (now Burkina Faso).

Jubilation in Britain

British diplomats gloated over Kwame Nkrumah’s defeat. “Nyerere and Sekou Toure [of Guinea] had the most effective influence on the other delegations,” F.S. Miles, Britain’s acting high commissioner in Dar es Salaam, Tanganyika, wrote in a cable to D.W.S. Hunt, an official of the British high commission in Kampala, Uganda, on October 18, 1963, saying the two presidents “were largely responsible for the final result, which was to reject the largely Nkrumahist doctrine of an immediate overall political union and accept instead a process of gradualism.”

Miles added that “anything we can do, without attracting attention, to build up Nyerere, for example, would undoubtedly be useful – and he looks as though he needs it because in my view he is coming off second best in his struggle with Nkrumah.”

“Nkrumah is our enemy, he is determined to complete our expulsion from an Africa which he aspires to dominate absolutely,” Dr. J.W. Russell, the British ambassador in Addis Ababa, wrote in a letter marked confidential to R.A. Butler in the Foreign Office in London on December 31, 1963. “Nkrumah’s ‘political kingdom’ seems irreconcilable with the independence, prosperity, or unity of others. And scruples he has none. How then is this lethal rogue to be contained?”

Calling Nkrumah a “mammon of unrighteousness,” Dr. Russell said he could not imagine why Britain would want “to help the Saltimbanco of Accra engross the rest of Africa.” Instead, he asked Butler, “Would it not be more logical and in every way more profitable just to align ourselves according to our interests and our principles?”

Ergo, Russell concluded, “We must find blacks who can; and although it would be counter-productive publicly to damn them with our old colonial kiss, yet surely it is not beyond our ingenuity to find effective ways of affording them discreet and legitimate support?”

His first idea for how to accomplish that was the British Commonwealth, but he feared that the concept of Commonwealth unity as a cohesive force in Africa was “something wistfully carried forward from the early decades of the century but now, like Keats’ name, writ in water.”

At the Addis Ababa conference, he wrote, “I could see no faintest trace of Commonwealth solidarity or operational unit of purpose. We made in fact a sorry show. True, we had the best, in Abubakar [Tafawa Balewa] and Nyerere; but by God we had the worst too, in Nkrumah and Obote [Milton Obote of Uganda]. Ethiopia is worth supporting and that the older generation may yet survive long enough in Africa to help maintain the Pax post- Britannica.”

On January 3, 1964, Hunt in Kampala wrote to the British ambassador in Lagos, R.W.D. Fowler, praising him for “sticking up for Nigeria” and adding that “nothing would give me greater pleasure than to believe that Nigeria is the St. George who is going to slay the Ghanaian dragon.”

On May 22, 1964, the British high commissioner in Accra, G. G. Collins, sent an anonymous confidential analysis of Nkrumah’s gains and losses to C. E. Wool-Lewis of the West Africa Department in the Commonwealth Relations Office in London.

The paper, written the previous September, said that “even before he went to Addis Ababa, it was clear that Dr. Nkrumah would not get all he wanted.” As early as December 1962, it noted, the Ghanaian press had begun to attack the “African version of the Organization of American States,” which, it was believed, was being prepared by the Monrovia Group.

On his arrival at Addis Ababa in May 1963, it said, Nkrumah “must have been greeted with the report that the proposals for a Strasbourg-type parliament [of the European Union] which his emissaries had been canvassing in African capitals during March and April, had got nowhere with the Foreign Ministers at Addis Ababa and that the consensus of opinion among delegations was in favor of something much more like the IAMO Charter.”

Nevertheless, the letter continued, “[Nkrumah] did not lower his sights. He delivered a speech to the other African heads of state containing proposals which he knew would be rejected. When they were, he neither walked out nor sought a compromise; he signed a Charter which fell very far short of what he had advocated.”

Nkrumah, it said, had asked for a “Continental Government of a Union of African States with a common foreign policy and diplomacy, common citizenship and a capital city”; instead, “he got a loose organization which specifically provides for its members to be able to renounce their membership.”

Nkrumah had hoped that an African union would solve all border problems; instead, “he got a Commission of Mediation, and clauses among the Principles of the Organization referring to non-interference in the internal affairs of states and to un-reserved condemnation of subversive activities on the part of neighboring states.”

Nkrumah had asked for a continent-wide economic and industrial program that included a common market, a common communications system, and a monetary zone with a central bank and currency; instead, “he got only a promise that commissions for matters economic and social, educational and cultural, scientific and technical might be set up.

Instead of plans for a common system of defense, “he got only the promise of a defense commission.” And when the resolution to set up a Liberation Bureau was implemented, “Ghana was not included.”

However, the letter said, the Addis Ababa conference was not entirely “calamitous for Ghana’s foreign policy.” With 30 heads of government and the representatives of two other independent African countries, it was “certainly the largest meeting of heads of government ever held in Africa,” and that “was in itself a triumph and could reasonably be claimed as much by Dr. Nkrumah as the prototype of African nationalist heads of state.”

Even if it was “a looser organization than Dr. Nkrumah had wished,” the first real organization of all the independent African states had been established, it continued, and “out of the various commissions might grow the sort of machinery which Dr. Nkrumah envisaged.

“Many African leaders had paid at least lip service to the superfluity of regional groupings. A Liberation Committee had been formed, even if Ghana was not a member. If there had been coolness on the part of Sir Abubakar (et tu Sekou Toure), open attacks on Ghanaian subversion had not materialized, and relations between Dr. Nkrumah and the heads of government in Algeria and Uganda had blossomed.”

Finally, it concluded, “Dr. Nkrumah had availed himself of one more opportunity, as he himself put it, ‘to explain not only to one another present here but also to our people’ – in particular to the youth of Africa – the direction in which he hoped to lead them.”

On January 24, 1964, a few weeks after yet another assassination attempt on Nkrumah in Ghana, D.L. Cole of the British High Commission in Accra sent a dispatch, marked Secret, to Member of Parliament Duncan Sandys, Britain’s secretary of state for commonwealth relations, headed: “The attempted shooting of President Nkrumah: Ghana enters 1964.”

In many ways, it said, Nkrumah’s African policies “appear already to have been a disastrous failure. Amongst other African governments, he has made many enemies and few friends.” And his role in the practical achievements of the Addis Ababa OAU conference was “insignificant.”

“But it would be most unwise to write off President Nkrumah’s influence in Africa,” Cole cautioned. “The continent is still in turmoil and President Nkrumah has the single-minded ruthlessness and the political experience and skill to offer a dangerous appeal to the younger generation in Africa.

“And probably behind him, he has considerable Russian support. As we enter 1964, it seems inconceivable that his more grandiose designs could ever be achieved. But the danger remains that, along the way, his extremist activities may do considerable damage to Western interests and to the stability of Africa itself.”

Nkrumah’s anti-colonial rhetoric had vexed British officials in Africa before. “To us, it is particularly galling to have this egotist shouting at us to take off the brakes in the Rhodesias, Nyasaland, and Kenya, and drive faster down the road to independence, which we know much better than he does,” A. W. Snelling, then the British high commissioner in Ghana, had written to the Commonwealth Relations Office in a dispatch headlined “Ghana Stocktaking” in September 1961. “And his knack of giving expression to the feelings of so many Africans, who are all the time rapidly becoming more politically conscious, is exasperating. I can well understand the fury he arouses in London, and often share it myself.”

But a week earlier, on August 28, 1961, the Office of the High Commissioner for the UK in Accra had taken a calmer view, in a dispatch headed “Points on the credit side in favor of Nkrumah.”

“Barring occasional lapses, e.g. in Budapest, his African activities are not directed against us anything like so much as against other NATO powers in Africa, i.e., Belgium, Portugal and France. He privately admits that we do not practice neo-colonialism,” it said. “For all the talk, British business has done very well in Ghana on the whole and we get perhaps £15-20m per annum income from it apart from selling our £40m of exports. We cannot afford needlessly to jeopardize this position.”

On February 10, 1964, D.W.S. Hunt in Kampala again wrote to Ambassador Russell in Addis Ababa, saying he feared Ghana’s influence was increasing, after a mutiny that January in the Tanganyikan Army that British troops had helped put down. “It may well turn out that the Tanganyika mutinies represent a further gain to the extent that President Nyerere has lost prestige and influence, for he is the Redeemer’s most dangerous rival,” Hunt wrote. (“The Redeemer” was one of the titles given to Nkrumah at home in Ghana).

Still fighting on

Nkrumah was beaten but not fazed. At the OAU Summit in Cairo, Egypt, on July 19, 1964, he still fought for a United States of Africa. “We cannot afford to let the warning clearly illustrated by the East African Federation go unheeded,” Nkrumah told the meeting. (The federation was a fizzling attempt to unite the former British colonies of Kenya, Tanganyika, and Uganda). “If, in the short period of the independence of the East African states, the careers and ambitions of political leaders are already strong enough to delay a regional grouping, how much more will every year’s delay make a continental union impossible of realization?

“Not only the careers of ministers, but thousands of entrenched bureaucratic posts will raise formidable barriers against the establishment of a Union Government [for Africa]. We saw the futility of this at Addis Ababa and thus our Charter condemned and abolished political groupings of any kind in our continent.”

Here again, it was all in vain. But at the 1965 OAU Summit in Accra, Nkrumah continued to push for a union government for Africa. Again, the African leaders were not prepared to move an inch.

‘Had we known’

But on March 6, 1997, Julius Nyerere, now chastened by the more than three decades of African non-progress since the Addis Ababa conference, told celebrants at Ghana’s 40th independence anniversary in Accra that “Nkrumah was right, we were wrong.”

Invited as the main guest speaker by then President Jerry Rawlings, Nyerere, who had retired as president of Tanzania in 1985, heaped praise on Nkrumah to the Ghanaians. “Kwame Nkrumah was your leader, but he was our leader too, for he was an African leader,” he said. “People are not gods. Even the best has their faults, and the faults of the great can be very big. So Nkrumah had his faults. But he was great in a purely positive sense.

“He was a visionary. He thought big, and he thought big for Ghana and its people and for Africa and its people. He had a great dream for Africa and its people. He had the well-being of our people at heart. He was no looter. He did not have a Swiss bank account. He died poor. Shakespeare wrote that ‘the evil that men do lives after them,’ but ‘the good is oft interred with their bones.’”

Nyerere called Kwame Nkrumah “the great crusader of African unity”. Nkrumah had wanted the Accra Summit of 1965 to establish a union government “for the whole of independent Africa,” Nyerere said, “but we failed. The one minor reason is that Kwame, like all great believers, underestimated the degree of suspicion and animosity, which his crusading passion had created among a substantial number of his fellow heads of state. The major reason was linked to the first: Already too many of us had a vested interest in keeping Africa divided.”

Before Tanganyika became independent in 1961, Nyerere said, “I had been advocating that East African countries should federate and then achieve independence as a single political unit. I had said publicly that I was willing to delay Tanganyika’s independence in order to enable all the three mainland countries [Kenya, Tanganyika, and Uganda] to achieve their independence together as a single federated state. I made the suggestion because of my fear – proved correct by later events – that it would be very difficult to unite our countries if we let them achieve independence separately.

“Once you multiply national anthems, national flags, and national passports; seats of the United Nations; and individuals entitled to a 21-gun salute, not to speak of a host of ministers, prime ministers and envoys, you would have a whole army of powerful people with vested interests in keeping Africa balkanized. That was what Nkrumah encountered in 1965.”

After the attempt to establish the union government at the Accra Summit failed, Nyerere said, “I heard one head of state express with relief that he was happy to be returning home to his country still head of state. To this day, I cannot tell whether he was serious or joking. But he may well have been serious, because Nkrumah was very serious, and the fear of a number of us to lose our precious status was quite palpable.”

However, Nyerere insisted that the 1965 meeting could not have delivered a union government for Africa, because it was “clearly an unrealistic objective for a single summit.”

The African leaders did not even discuss a mechanism for pursuing the objective of a politically united Africa, Nyerere disclosed. “We had a Liberation Committee already,” he said. “We should have had at least a Unity Committee or undertaken to establish one. We did not. And after Kwame Nkrumah was removed from the African scene [by a military coup in 1966], nobody took up the challenge again.”

In his 1997 book Sowing the Mustard Seed, Uganda’s long-serving president, Yoweri Museveni, wrote that there had been talk that the British and the Americans were behind the idea of the East African federation, “so that, on the one hand, they would neutralize the Zanzibar Revolution by absorbing it into a wider entity and, on the other hand, frustrate Kwame Nkrumah’s dream of uniting the whole of Africa. There is now evidence to show that the frustration of these ventures had the backing of American and British imperialism.”

A confession and a plea

Nyerere told the celebrants in Accra that he had “a confession and a plea. The confession is that we of the first-generation leaders of independent Africa have not pursued the objective of African unity with vigor, commitment, and sincerity that it deserved. Yet that does not mean that unity is now irrelevant. Does the experience of the last three or four decades of Africa’s independence dispel the need for African unity?

“With our success in the liberation struggle, Africa today has 53 independent states, 21 more than those which met in Addis Ababa in May 1963,” he continued. [South Sudan’s independence in 2011 made it 54.] “If numbers were horses, Africa today would be riding high! Africa would be the strongest continent in the world, for it occupies more seats in the UN General Assembly than any other continent.

“Yet the reality is that ours is the poorest and weakest continent in the world. And our weakness is pathetic. Unity will not end our weakness, but until we unite, we cannot even begin to end that weakness. So this is my plea to the new generation of African leaders and African peoples: work for unity with the firm conviction that without unity, there is no future for Africa.”

Nyerere rejected “the glorification of the nation-state” as inherited from colonialism, and called Africa’s numerous countries “artificial nations we are trying to forge from that inheritance.”

“We are all Africans trying very hard to be Ghanaians or Tanzanians,” he said. “Fortunately for Africa, we have not been completely successful. The outside world hardly recognizes our Ghanaian-ness or Tanzanian-ness. What the outside world recognizes about us is our African-ness.”

The future of Africa and its modernization for the 21st century “is linked with its decolonization and detribalization,” Nyerere continued. “A new generation of self-respecting Africans should spit in the face of anybody who suggests that our continent should remain divided and fossilized in the shame of colonialism, in order to satisfy the national pride of our former colonial masters.

“Africa must unite! That was the title of one of Kwame Nkrumah’s books. That call is more urgent today than ever before. Together, we, the peoples of Africa will be incomparably stronger internationally than we are now with our multiplicity of unviable states. The needs of our separate countries can be, and are being, ignored by the rich and powerful. The result is that Africa is marginalized when international decisions affecting our vital interests are made.

“Unity will not make us rich, but it can make it difficult for Africa and the African peoples to be disregarded and humiliated. And it will, therefore, increase the effectiveness of the decisions we make and try to implement for our development.”

Nyerere was speaking in 1997, 34 years after he, Balewa, and 23 other African presidents had voted to refuse Nkrumah’s idea of a strong African union.

The European Union

Today, 58 years down the road from 1963, it is interesting to compare what the Europeans who worked to undermine Nkrumah’s African union project have done for themselves via the European Union (EU).

The EU grew out of the European Coal and Steel Community, set up in 1950 by Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands. It was founded with the ambitious aim of ending the frequent wars between European neighbors, more than 20 centuries of carnage that culminated in the slaughter of millions from Liverpool to Stalingrad (now Volgograd) in World War II.

Today, the European Union has generally succeeded in bringing peace, cooperation, prosperity, and one voice to Europe. The last major war fought by Europeans against Europeans started in 1945, with the arguable exception of the bloody ethnic conflicts in the former Yugoslavia in the 1990s. The voice of Europe as a group is respected around the world.

Like Nkrumah’s pan-African work prior to the founding of the OAU, the idea of a European union gathered strength during the years between World War I and World War II. “The consciousness that national markets in Europe were interdependent though confrontational, along with the observation of a larger and growing US market on the other side of the ocean, nourished the urge for the economic integration of Europe,” according to the EU website.

In 1920, the British economist John Maynard Keynes advocated that “a Free Trade Union should be established … to impose no protectionist tariffs whatever against the produce of other members of the Union.”

Keynes’ integration suggestion was taken up by Richard von Coudenhove-Kalergi, an Austrian-Japanese politician and philosopher, who founded a Pan- Europa Movement in 1923 to give flesh to the “United European State” idea.

Influenced by Coudenhove-Kalergi’s views, French Prime Minister Aristide Briand in 1929 spoke at the League of Nations (the precursor of the United Nations) about the virtues of a European union.

In March 1943, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill took up the call in a radio address in which he spoke about “restoring the true greatness of Europe” once victory in World War II had been achieved. He pondered the creation, after the war, of a “Council of Europe” which would bring the European countries together to build peace. In September 1946, in a speech at the University of Zurich in Switzerland, Churchill explicitly advocated the creation of a United States of Europe.

Kwame Nkrumah therefore was in good company in May 1963 when he called for the emergence of a United States of Africa.

In 1948, a congress in The Hague, the Netherlands, became a pivotal moment for Europe as it led to the creation of a European Movement International and a College of Europe, where future European leaders would live and study together. Belgian foreign minister Paul-Henri Spaak proposed a “European Assembly,” a continental legislature, while Great Britain wanted a more advisory body.

The compromise was the Council of Europe, which consisted of a Consultative Assembly, meeting in public, and a Committee of Ministers, which met in private and had decision-making powers. The treaty establishing it was signed on May 5, 1949, by 10 nations: Belgium, France, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Ireland, Italy, Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. At first, it concentrated on “further realization of human rights and fundamental freedoms.”

Putting words into action

Many Europeans consider May 9, 1950 the foundation of today’s European Union. It was the day when the French foreign minister, Robert Schuman, made an extraordinary declaration based on two core principles: peace and solidarity, and announced the creation of a European Coal and Steel Community. Schuman later became known as the “Father of Europe,” while May 9 was designated as “Europe Day,” much like May 25 is “Africa Day.”

“Europe will not be made all at once, or according to a single plan,” Schuman argued. “It will be built through concrete achievements which first create a de facto solidarity. The coming together of the nations of Europe requires the elimination of the age-old opposition of France and Germany.”

The first step, he proposed, should be putting Franco-German production of coal and steel under a common authority, open to participation by the other countries of Europe. That, he said “will change the destinies of those regions which have long been devoted to the manufacture of munitions of war, of which they have been the most constant victims.”

In a famous quote, he declared that establishing that solidarity in production “will make it plain that any war between France and Germany becomes not merely unthinkable, but materially impossible.”

Other Western European leaders, such as Spaak, Italian Prime Minister Alcide de Gasperi, French economic adviser Jean Monnet, and West German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer, agreed. On April 18, 1951, the treaty establishing the European Coal and Steel Community was signed in Paris.

After ratification by Belgium, Germany, France, Italy, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands (known as the “Inner Six”), it went into effect on July 23, 1952. The treaty’s immediate objective was to establish a common market for coal and steel, and also to lay the foundation of an economic community that would gradually become a political union.

In June 1955, a conference was held in Messina, Italy, to develop the concept of a European common market. Two years later, on March 25, 1957, the concept was embodied in the Treaty of Rome, which was signed by the Inner Six and went into effect on January 1, 1958. This marked the beginning of the European Economic Community (EEC) or “Common Market” and the creation of a customs union.

The Inner Six also signed another treaty in Rome, creating the European Atomic Energy Community (Euratom) to cooperate in the area of nuclear energy development. It also went into effect in 1958.

Europe, therefore, had three “communities” running concurrently at the time: the European Coal and Steel Community, the European Atomic Energy Community, and the EEC. However, during the 1960s, tensions began to grow among the three, and therefore

in 1965 an agreement, called the Merger Treaty, was reached to combine them on July 1, 1967. The entity that came out of the merger was collectively referred to as the European Communities.

Then, on November 1, 1993, the European Union was formally established when the Maastricht Treaty came into force. The EU’s membership gradually increased to 28 nations, largely with the addition of the formerly Soviet-dominated countries of Eastern Europe, although it fell to 27 with the exit of Britain on December 31, 2020.

The achievements

In 1986 the Single European Act was signed. This treaty provided the basis for a vast six-year program to sort out the problems with the free flow of trade across EU borders, and thus created the “Single Market.” In 1993, the Single Market was completed with “four freedoms”: movement of goods, services, people and money. A small village in Luxembourg called Schengen gave its name to the 1985 “Schengen Agreement” that gradually allowed Europeans to travel within the continent without having their passports checked at the borders.

Since then, 22 of the 27 EU member states have abolished passport controls for EU members, creating what is called the “Schengen Area,” in which their citizens can cross borders freely and work in other countries. A common EU citizenship was established by the Maastricht Treaty.

In 1999, the EU established a monetary union that gave birth to the euro, the EU’s common currency, in 2002. The euro was initially introduced for 12 EU member states, but seven more countries later joined the eurozone, bringing the current total to 19 states.

In 2012, the EU, with a total population of 447 million, was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for having “contributed to the advancement of peace and reconciliation, democracy, and human rights in Europe.”

The EU has a standardized system of law that applies in all member countries. In 2020, it had about 5.8% of the world population and a nominal gross domestic product of around US$17.1 trillion, 18% of the world’s nominal GDP.

The EU also has a common foreign and security policy that gives it a role in external relations and defense. It has its own permanent diplomatic missions throughout the world, and represents itself at the UN, World Trade Organisation, G7, and G20, with its global influence making it a political and economic superpower to match the United States and China.

Conclusion

In sum, the EU has achieved a lot for Europeans in the 58 years since May 1963, when Europe’s old colonial powers and the U.S. backed the African leaders who killed Nkrumah’s African union project.

The EU’s richer nations have often, though not always, looked after the poorer member states, mostly in southern Europe. Borders have come down in Europe. Free movement of EU citizens is assured. There is a common agricultural policy, a common currency, a common European Bank, a common foreign policy and diplomacy, a common security or defense policy, a common market (or single market), and much more – all the things Nkrumah envisioned for Africa in the 1960s.

In contrast, Africa has seen the loose union it forged in May 1963, then called the Organization of African Unity, morph into the African Union (AU), on June 9, 2002. But unlike the EU, AU institutions have no teeth. They have remained paper tigers.

No one takes the decisions of the Pan-African Parliament, based in Johannesburg, South Africa, seriously. The African Court of Justice is disregarded by member states. Worse, the failure to achieve the things that Nkrumah proposed in 1963 stand as a crying shame of the continent, which appears to enjoy empty talk more than concrete action.

Nkrumah had nine major proposals in 1963. First, a common economic and industrial program for Africa. This remains unachieved 58 years later. Second, a common market for Africa – unachieved. The recently established African Continental Free Trade Area (AFCTA) exists more on paper than on the ground. Third, an African common currency – unachieved. Fourth, an African monetary zone – unachieved. Fifth, an African central bank – unachieved. Sixth, a continental communication system – unachieved. Seventh, a common foreign policy and diplomacy – unachieved. Eighth, a common system of defense – unachieved. Ninth, a common African citizenship – unachieved. In fact, foreigners today have freer access to African countries than Africans from other nations on the continent do.

“Africa is a victim of history and geography,” then Japanese foreign minister Masahiko Komura said in 1999 at a conference on African development in Tokyo. Historically, Europe has played a generally disastrous role in the life of the African continent. Geographically, Africa is too close to Europe for comfort. Europe feels threatened if Africa decides to rouse itself, fearing that Africa will use its vast resources for itself, at the detriment of European life and industry.

And so, even today, the role Europe plays in the halls of the weakened African Union in Addis Ababa is not in the interest of Africa and Africans. Unfortunately, the current African leaders, like their counterparts in the first generation after independence, are playing along. African eyes never see, it appears. Neither do African ears hear.