Over the last 15 years, international donor organizations have given more than $700 million to the U.S. firm Cepheid to supply its rapid disease-testing equipment to developing countries particularly African nations at a discount. When the COVID-19 pandemic struck, Cepheid most its COVID-test cartridges to wealthy nations who could afford to pay more and left African countries hanging. David Lewis and Allison Martell report.

For much of last year, the coronavirus crept, undetected, across the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. Test samples had to be sent more than 1,500 kilometers from remote hospitals to the capital Kinshasa. Results took weeks to come back. Some of the infected returned home, spreading the virus. In Bukavu, the capital of South Kivu province, bodies piled up in the morgue. Senior doctors described total confusion. Five doctors and 10 nurses were among those who died, according to one medic who spoke on condition of anonymity.

It needn’t have been this way. Bukavu’s Provincial General Reference Hospital, like dozens of others across Congo, had access to a machine that could have processed around 100 COVID-19 tests a day, if only it had the right chemical kits, doctors said.

In March 2020, the California-based medical-diagnostics firm Cepheid, a unit of the Danaher Corporation science and technology conglomerate, began supplying a rapid and highly accurate COVID-19 test that seemed perfectly suited to Congo’s needs. Nearly 5,000 of Cepheid’s GeneXpert diagnostic devices had already been deployed in health facilities across Africa as part of the battle against tuberculosis, Ebola, HIV, and other infectious diseases, with 130 of them in Congo. Medical staff would need little training to learn how to use them to test for COVID-19, and the results would be ready in hours, not weeks.

Starting in 2006, donor organizations put their faith in Cepheid equipment to help tackle deadly diseases in countries that lack medical laboratories and skilled personnel to run them. To date, donors have committed more than $730 million to the development and distribution of GeneXpert systems and their testing cartridges, mainly in Africa, Latin America, and parts of Asia. The U.S. military and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, a Geneva-based charity, are among those who have provided funding.

But a year on from the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, many of Congo’s GeneXpert machines are gathering dust. The reason: a shortage of proprietary chemical cartridges, also made by Cepheid, that are needed to conduct COVID-19 tests. Each test uses one cartridge.

Health experts say Africa is being priced out of the market. Buyers in the United States and Canada are paying $30 to $50 for each cartridge, according to laboratory sources in North America and a regional Canadian policy document. That’s roughly double the $19.80 discounted rate secured for poorer countries, including Congo.

Cepheid isn’t breaching any contract by directing supplies to the U.S. and other wealthy markets, because there isn’t one, health officials said. But it did pledge to set aside 1.55 million cartridges for a World Health Organization (WHO)-led consortium of 144 poorer nations, including all of Africa, in the crucial early months of the pandemic. Yet less than a fifth of that total was delivered from April to August 2020, WHO data show. Shortages have continued since then. By late 2020, Cepheid had still delivered less than a third of the amount it promised.

Many of the countries in the consortium are heavily dependent on GeneXpert machines. The medical charity Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF), or Doctors Without Borders, has calculated that Cepheid could sell its cartridges for $5 apiece and still make a profit – a figure the company disputes as “not at all reflective of reality.”

Where did the cartridges that Cepheid pledged to the consortium for that April- August period end up, and how much were they sold for? If buyers paid more than the $19.80 discounted rate agreed to with the consortium, Cepheid would have boosted its sales by at least a few million dollars. If it sold them for the $50 paid by some North American customers, it would have raked in more than $30 million.

Cepheid responded that it has supplied COVID-19 tests to over 130 countries globally, has raised production and is working hard to expand capacity further to meet demand that “continues to be much higher than supply in every region.”

“We have worked with the consor-tium and the WHO allocation model to be as fair and equitable as possible in the split of the available volumes,” Cepheid said in a statement. It noted the company supplied record numbers of TB tests to low and middle-income nations in 2020, despite the pandemic. Cepheid didn’t directly address the 1.55 million cartridges pledged to the consortium, nor did it comment on the high estimates of its sales boost. Danaher has said in quarterly earnings that Cepheid’s revenues have soared over the past year, and it is installing GeneXpert devices globally at a record rate.

Bukavu’s Provincial General Reference Hospital declined to comment about shortages affecting its ability to do COVID-19 tests.

Testing capacity

For Africa, testing is critically important. While wealthy countries are rolling out vaccines, African nations are still largely reliant on testing to suppress the virus. Many are facing a resurgence of COVID-19. Yet across the continent, testing capacity is among the lowest in the world.

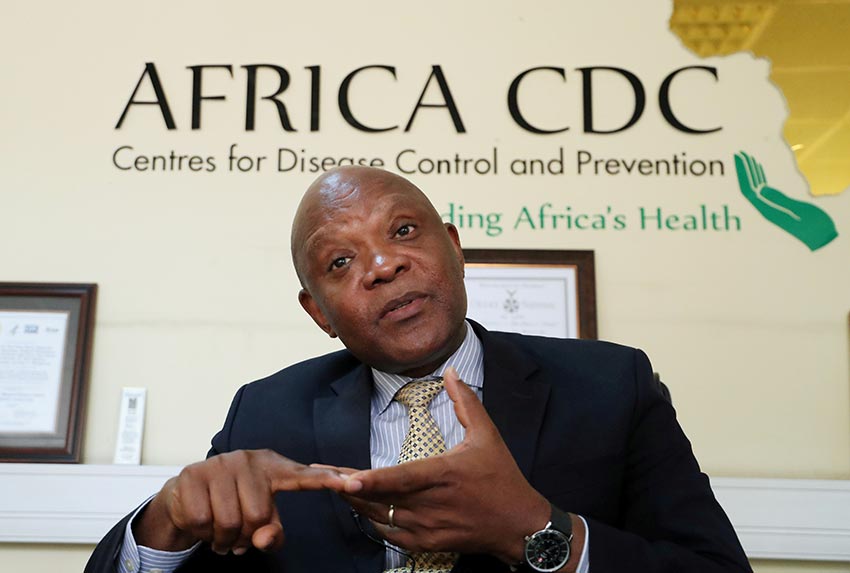

“It is a pity because this is a diagnostic instrument that would have helped us to be ahead of a pandemic,” said John Nkengasong, director of the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC).

For Nkengasong, there are echoes of the early years of the HIV/AIDS epidemic when millions died in Africa because they did not have access to life-saving antiretroviral drugs. Africa’s death toll from the new coronavirus – over 103,600 according to a Reuters tally – is lower than the annual toll for HIV/AIDS. Still, Nkengasong said African countries are being “elbowed out” of the market for COVID-19 diagnostics and vaccines.

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, some governments had warned against relying so heavily on one company to meet their testing needs, according to a 2017 study for a United Nations (U.N.) agency.

The WHO didn’t comment on the study’s findings, but said it encourages countries to consider a range of test types and technologies to meet their needs. The organization shares the frustrations of poor countries that more cartridges weren’t made available, said WHO diagnostics expert Lara Vojnov.

“This is a business decision by Cepheid,” she said. Cepheid “has chosen to provide” a relatively small percentage of its total production to low and middle-income countries, and “the remaining volumes go to high- income settings.”

The first batch of Cepheid chemical cartridges arrived in Congo in June. So few were delivered that they had to be rationed, and they quickly ran out in the country of 90 million people. One of the leaders of eastern Congo’s coronavirus response, Nobel-prize winning Dr. Denis Mukwege, resigned that month, partly in frustration over the inability to test locally. He declined to comment for this article. Early in the pandemic, extra laboratory staff were sent to Kinshasa to help process samples centrally, said Dr. Daniel Mukadi, a director of the National Institute of Biomedical Research in the city of Goma.

Donor organizations referred questions about the allocation of COVID-19 tests to the WHO and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, which together managed the procurement process.

A spokesman for the Global Fund said “supply availability for Cepheid tests has been the primary constraint since the start of the pandemic.”

The charity’s conversations with Cepheid have “over time increased the supply made available to low- and middle-income countries,” he added. WHO diagnostics specialist Vojnov confirmed there was a big supply shortfall through much of 2020, improving towards year-end.

Public health revolution

Cepheid’s GeneXpert was launched in 2005 for clinical applications. Tests that had previously required a laboratory, trained staff, and multiple instruments could now be conducted by putting a sample into a cartridge and loading it into the GeneXpert diagnostics device. The cartridge is a kind of miniature lab, prefilled with reagents to detect genetic material associated with infection. The system is considered as good as or better than non-automated Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) tests.

The next year, Cepheid won a key funding partner: the Geneva-based Foundation for Innovative New Diagnostics (FIND), a non-profit organization set up with financial backing from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. FIND offered funding for a new test for drug-resistant tuberculosis. Cepheid has also received $120 million in funding from the U.S. military, according to a 2011 presentation by the Gates Foundation. A Department of Defense official said she couldn’t confirm the figure.

Cepheid’s tuberculosis test was ready to roll out by 2009, winning an endorsement from the WHO. By 2016, Cepheid had accepted some $68.1 million from FIND and other public or nonprofit organizations to develop its technology and offer discounts to developing countries. Donors sponsored the installation of thousands of GeneXpert machines to test for TB.

“We called it a public health revolution,” said Sharonann Lynch, a policy advisor for MSF. “Here was a test that you could get a turnaround in hours instead of weeks. What a breakthrough.”

In the 15 years to 2016, Cepheid only turned an annual profit once. But as the number of installations grew, there was reason for optimism: Every new device locks in years of demand for Cepheid’s test cartridges, because there are no competing suppliers.

Investors got their payday in September 2016, when Danaher said it would buy Cepheid for $4 billion, a 54% premium on its stock. Danaher’s then chief executive, Tom Joyce, touted Cepheid’s “razor-blade business.”

Joyce was referring to the way sales of the GeneXpert machine, as with sales of razors, create demand for cartridges, thus driving more revenue over time than does the machine itself, which costs $11,000 and upwards. He also praised the device’s global reach, larger than any competing diagnostic system. Danaher promised to make Cepheid profitable.

The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria said it approved grants worth over $542 million to help developing countries buy GeneXpert platforms, cartridges and support laboratories over the period 2017 to 2023.

By early 2020, Africa had nearly 5,000 GeneXpert devices, capable of processing more than 21,000 tests at a time, according to the Africa CDC, a disease control body set up by the African Union in 2017. Cepheid has said more than 10,000 of the 30,000 GeneXperts worldwide are in low and middle-income countries.

Not everyone thought a heavy reliance on Cepheid was a good idea.

UNITAID, a U.N. agency that supports healthcare research and technology in poorer countries, commissioned the Dalberg consulting firm to produce a report about the Cepheid TB program. The 2017 report warned of a “potentially monopolistic arrangement” that risked keeping prices artificially high and stifling innovation. It said some unnamed governments were concerned that donors had focused their spending on a single manufacturer.

A UNITAID spokesperson said the agency had responded by partnering with other companies “to create competition and put pressure on pricing and availability – all in an effort to create a healthy market.” Dalberg said it couldn’t comment on its report.

“Frozen out”

When COVID-19 started spreading in early 2020, just two African nations – South Africa and Senegal – had laboratories capable of testing for the disease.

In March, major diagnostics companies such as Roche Diagnostics, Abbott Laboratories and Cepheid all released cartridges capable of detecting COVID-19 for their automated platforms.

But some countries, including Chad and Sao Tome and Principe, only had Cepheid’s GeneXpert machines at the time, according to the Africa CDC.

Other countries, including Nigeria and South Africa, wanted to use GeneXpert machines to bring on-site testing to hospitals and clinics, often in remote locations, and quickly establish which patients needed to be isolated in COVID-19 wards. Uganda and Kenya wanted to deploy them to their borders to test truck drivers before allowing them in, easing the kilometers-long queues that built up while samples were sent to laboratories.

The Africa CDC estimates there are enough Cepheid GeneXpert machines installed across the continent to carry out 1.6 million tests a week. There are far fewer Abbott and Roche platforms: Abbott machines have a total capacity of just under 200,000 tests, and Roche’s of around 275,000. A Roche spokesman said the company has delivered over 2.5 million PCR tests to Africa to date – directly to governments and via the WHO-led consortium. Abbott didn’t comment.

The Africa CDC projected that the continent would need 4.4 million Cepheid COVID-19 test cartridges for the year from April 2020, according to a spokesman.

But better-funded health systems in hard-hit cities such as New York were also desperate for cartridges. Public health experts knew there would be a fight for supplies. In March, the WHO set up its Diagnostics Supply Consortium for COVID-19, made up of a mix of U.N. agencies, health-focused organizations and donors, to coordinate the purchase of tests for poorer countries.

Minutes from the consortium’s first meeting on March 31, 2020 reveal the urgency.

“Deals need to be struck by the end of this week or early next week. Otherwise, the countries and people that the consortium members represent will get frozen out of the market as the pandemic continues to grow,” said Ira Magaziner, founding chief executive of the Clinton Health Access Initiative, established with the former U.S. president.

Magaziner struck a hopeful tone. “The consortium members represent a sub- stantial part of diagnostic companies’ business,” he said, according to the minutes. “Businesses will hopefully support their long-term customers.”

Magaziner did not respond to questions sent via the Clinton organization, which referred all requests for comment to the WHO and others.

The consortium began discussions with major test suppliers, including Cepheid. By April 8, Cepheid had committed to set aside 1.55 million tests for the consortium from late April to early August, more than a third of its planned production at the time, according to a consortium report. Low and middle-income countries would pay $19.80 a test. That’s within the range of Cepheid’s discounted prices for other tests: a TB test costs $9.98, one for HIV $14.90, and one for Ebola $19.80. It’s also in line with other manufacturers’ prices for COVID-19 tests.

Two weeks later, TB experts from around the world, many of whom had been drawn into the coronavirus response, attended a webinar with Cepheid executives. At the session. Devasena Gnanashanmugam, senior director for medical affairs at Cepheid, said the firm’s COVID-19 test “will probably be one of the tests that is most accessible to low and middle-income countries,” given the number of machines already installed. Consortium members believed Cepheid was ready to play a significant role.

But at the next consortium meeting, on April 28, the Clinton Health Access Initiative relayed disappointing news, according to the minutes: Cepheid said shipments it had committed to U.N. children’s agency, UNICEF, and five large countries would “count against the allocation” to the consortium. In other words, Cepheid would deduct these shipments from the 1.55 million it pledged. The company would eventually cut supply to the consortium over the period from May through August to just 437,000 cartridges, said WHO diagnostics specialist Vojnov. UNICEF said in a statement it too expressed concern that some “point of care” tests, such as GeneXpert, were “critically limited.”

Meanwhile, Cepheid’s business was booming. On May 7, reporting its first quarter financial results, Danaher’s then-CEO Joyce said, “We’re flat out at Cepheid.”

“We are continuing to expand our capacity, but every test that we produce every single day gets shipped, and the demand is continuing to build.”

Joyce said newly installed GeneXperts would help the company sell other tests and gain market share even after the pandemic.

When Danaher released second quarter earnings in July, Joyce said demand for COVID-19 tests and GeneXpert instruments “helped drive more than 100% core revenue growth” at Cepheid over the three months. The firm had installed four times as many GeneXperts as in a typical quarter.

Cepheid was producing 2 million COVID-19 test cartridges a month, and would go on to ship more than 24 million in 2020. The company didn’t provide a breakdown of destinations.

Yet by July 27, fewer than 80,000 cartridges had been delivered to countries in the WHO consortium, according to minutes of a July 28 consortium meeting. The minutes note that the Global Fund had heard from unnamed colleagues that Cepheid suggested “huge pressure for volumes from the U.S. market” was to blame for the shortfall.

By November, Cepheid had delivered or committed to deliver around 800,000 cartridges through the consortium and under deals struck before the system launched, according to WHO diagnostics specialist Vojnov.

By Feb. 8, a total of 2.82 million cartridges had been delivered or were in transit to consortium members worldwide, Vojnov said. Just over half of those were for Africa. The number of tests set aside via the WHO consortium still accounted for little more than 10% of Cepheid’s overall production. And health facilities in Congo were still running out of cartridges for their GeneXpert machines.

MSF’s Lynch said Cepheid ought to have allocated more to poorer countries, given how much it had expanded its business in the developing world largely through donor support.

“There is no excuse for the fact that those consoles, those machines are now empty,” Lynch said. “I mean, it’s such a dramatic picture of inequity in terms of where Cepheid is choosing to sell.”

Little room to negotiate

The coronavirus’ toll in Africa has not so far been as severe as some had feared. Still, many countries are grappling with a second wave of infections and new variants of the virus that are putting pressure on their public health systems. It is also unclear how many deaths may have been missed: Most deaths of all kinds go unrecorded in Africa, and testing rates remain low.

As rich nations cheer early vaccination drives, most countries in Africa are still waiting for their first shots from a global vaccine-sharing initiative co-led by the WHO and an African Union. From Senegal to Nigeria to South Africa, hospitals are filling up, and there are shortages of oxygen. Lockdowns that could help turn the tide in Europe and the United States are impossible in countries where most people depend on daily earnings to survive. So, finding and isolating patients before they infect others remains the best hope for containing the virus. But tests remain in short supply.

In Congo, just seven laboratories, five in Kinshasa, one in Goma, and one in Bukavu, can carry out manual PCR tests to detect COVID-19. The rest of the country still relies on GeneXpert devices, as do seven labs in Kinshasa. In late November, Congolese labs had around 1% of the GeneXpert cartridges they needed, a government database showed. By early 2021, more supplies had arrived, but the situation hadn’t changed radically, an official involved in the response said.

Congo, with a population of 90 million, has carried out just over 124,000 COVID-19 tests, according to Africa CDC data.

In Uganda, where GeneXpert machines are “scattered all over the country,” cartridge supplies remain unreliable, said Stephen Balinandi, principal researcher at the Uganda Virus Research Institute in Entebbe. By mid-August, after waiting two months for an order of thousands of cartridges that never arrived, institute staff packed their GeneXpert back into its box and stored it away.

“It was occupying space for nothing,” Balinandi said.

In Nigeria, health officials saw GeneXpert systems as “quick wins” while they trained laboratory staff to do more complex PCR testing, as there were over 300 in the country. But it was not to be.

“The global supply has meant that we’ve been provided a very limited number” of cartridges, said Chikwe Ihekweazu, director general of the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control.

South Africa, home to the continent’s most sophisticated health system and nearly a third of its confirmed coronavirus cases, wanted to use its 325 GeneXpert machines in remote locations.

“There are many hundreds of health-care staff in South Africa who can operate these machines,” Wolfgang Preiser, a virologist at Stellenbosch University, said. But his own laboratory received very few tests, and many peripheral labs never received any, he said. “I have to say, it was painful.”

Even if Cepheid’s production ramps up, and vaccines reduce demand for tests in wealthier nations, poorer countries will still face a cost barrier, MSF said.

The group commissioned a series of analyses on the cost of producing various versions of the GeneXpert cartridge. It argues that Cepheid could sell the COVID-19 cartridge for $5 and still make a profit, based on the price of materials and the company’s strong sales volumes in recent years. Cepheid disputes this figure, saying the analysis is “simply not accurate.” The company has said it won’t share details about its costs because this is “highly competitive and sensitive information.”

David Branigan, TB project officer at the U.S. patient-advocacy organization Treatment Action Group, said the WHO consortium should have pushed for affordable prices in its discussions with Cepheid. The WHO’s Vojnov said Cepheid’s proprietary technology left little room to negotiate.

Nkengasong, of the Africa CDC, fears a repeat with vaccines. Nations will protect their own “and you will be left hanging,” he said.

“That is what we have seen with diagnostics. And that is what we will see with the vaccine race.”

The global vaccine-sharing scheme co-led by the WHO, aimed at making access to shots more equal, delivered its first shipment to Africa on Feb. 24, when a flight carrying the AstraZeneca/Oxford vaccine landed in Ghana’s capital, Accra.