French President Emmanuel Macron wants to fix the country’s relations with Africa. But he’s going about it the wrong way. Rather than change the unequal economic system that is the legacy of colonialism, he is reviving the 1950s-1960s strategy of cultural diplomacy. Frank Gerits reports.

French President Emmanuel Macron has committed himself to remaking the country’s relationship with Africa. In 2017, six months after his inauguration, he visited the University of Ouagadougou, in Burkina Faso, where he gave a speech announcing a new French policy that focused on African youth.

He wanted to forge a new connection with Francophone and Anglophone Africa while also acknowledging the traumas that French colonialism had caused. The Algerian War of Independence from France, between 1954 and 1962, for instance, is still an open wound to many in Africa.

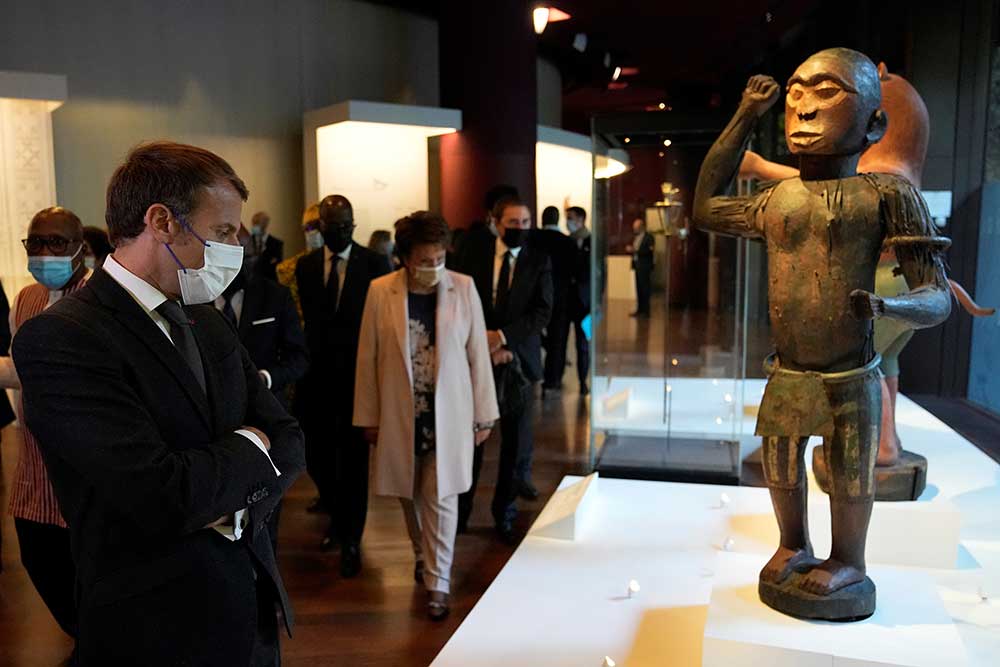

Macron followed his visit four years later with a key event showcasing the new direction of Afro-French relations. He hosted the New France-Africa Summit in Montpellier, France, on Oct. 8, 2021.

Civil-society representatives from France and Africa met to discuss topics such as “citizen engagement and democracy” and “doing business and innovating.” The summit was organized with the help of Cameroonian intellectual and philosopher Achille Mbembe, who was also asked to write a report on the French-African relationship.

The summit was billed to be “radically different.” Rather than having heads of state in attendance, young people debated one another. In one roundtable discussion, young African entrepreneurs accused Macron of perpetuating French neo-colonial policies in Africa. They cited France’s support for Mahamat Idriss Déby, who succeeded his late father as authoritarian leader of Chad in April.

This criticism of Macron’s approach is particularly painful for the French foreign affairs ministry, because the event was meant to move away from Françafrique, France’s approach to its sphere of influence in Africa built on personal alliances with African strongmen.

This form of realpolitik was started under President Charles De Gaulle (1959-1969) and reached an apex under Georges Pompidou (1969-1974). Jacques Foccart, who was secretary-general for African and Malagasy affairs under both presidents, became the point man. Known as “Monsieur Afrique,” he is considered to have been the mastermind behind several African coups.

Return to the past

Macron’s new approach – focusing on cultural diplomacy – is nothing new. It was tried in the 1950s without success.

A good outcome also seems unlikely this time around. That is because it is out of kilter with the worldview of Africans – a world made up of imperialists and anti- colonialists, where the need for the fundamental decolonization of society is constantly highlighted.

Macron’s plan also fails to acknowledge the injustices of an unequal economic system dominated by the global North at the expense of the South. In Macron’s view, addressing the “aspirations of young people” in Africa will improve international relations.

In line with this, France’s Africa strategy of the 1950s, which was built upon cultural diplomacy – an exchange of ideas, values, traditions, and other aspects of culture – is being revived.

After 1945, African trade unionists and other members of civil society began making political claims and called for a new relationship with Paris. Madagascar was in the grips of a violent nationalist revolt against France between 1947 and 1948. Dakar, the capital of Senegal, became the epicenter of anti-colonial activism as trade unions became more political, as shown by the general strike of 1946.

In response, French magazines such as Paris-Match and Bingo were offered in the cultural centers of French West Africa. It was part of a plan to spread French culture as a ladder to modernity and a higher societal position for Africans.

What was called modernization in the 1950s is today being rebranded by Macron as entrepreneurship. An example of this is “Digital Africa,” an initiative set up by the Agence française de développement to help tech startups in Francophone Africa.

Old recipe

The French leader’s willingness to venture beyond French-speaking Africa, as well as his reliance on an African intellectual (in this case, Mbembe) to sell his visions, is also an old recipe.

In October 1955, Léopold Senghor, then the minister responsible for international cultural matters in the French government of Prime Minister Edgar Faure, travelled to Lagos, Nigeria. The trip by one of the main intellectuals of Négritude, a literary movement based on Black pride, was meant to reinvigorate the link between French and African cultures.

Senghor, who was president of Senegal between 1960 and 1980, considered Négritude a means to jump-start modernization. French-language education in particular was important, since it facilitated the study of science and increased the social mobility of the lower classes. They would, like the elites, be able to familiarize themselves with France, which was in Senghor’s definition, a place of innovation and imagination.

By teaching more Africans French, more social classes would have access to all the science France had on offer. Senghor in effect turned Négritude – a way to reaffirm “Black” values, art and culture, with an emphasis on the French-African language and poetry – into an instrument of development. Mbembe has also been criticized by African intellectuals on similar grounds.

By the end of the 1950s, French cultural diplomats even believed they had something valuable to offer, and they expected diplomatic support in exchange for cultural products. Therefore, institutions such as universities, cultural centers, and language schools in places like Dakar and Accra had to be renovated. French books had to create an appetite for the French language by focusing on scientific, technical, and medical knowledge.

By foregrounding the services that France could offer, the French foreign ministry wanted to avoid hurting African nationalistic pride, which was at a high point as 1960, the year when 17 countries became independent, approached. Macron’s efforts at giving Africa tangible benefits, a bridge loan for Sudan for instance, is a throwback to that era.

Why Macron’s plan will fail

Why is Macron emulating old strategies?

A big part of the answer can be found in the fact that the international circumstances today are very similar to the post-World War II decade when the Soviets, the Americans, the British, and other African nationalists were all locked in a competition to win the hearts and minds of French Africa.

Africa’s economic growth and expanding political influence since 2000 have attracted external partners keen on building relations with the continent. Russia, China, Turkey, Japan, India, the United Kingdom, and France have all held regular summits with African states.

A cynical policy of weapon shipments and business deals would simply be ineffective in such an environment, where Africans are self-confident as a result of the economic improvements of the past decade. Therefore, Macron’s cultural strategy that targets civil society seems logical.

But it will remain ineffective if it does not acknowledge that many members of African civil society do not appreciate French interference. The testy interaction during the roundtable at Montpellier suggests as much.

It is, therefore, doubtful that the French return to the cultural-diplomacy strategy of the 1950s and 1960s will yield very different results. As long as leaders like Macron do not fully grasp the distaste for French interventions in African affairs, no amount of cultural products or young people will improve the Afro-French relationship.