Ghana’s December 2020 general election was a big shambles. There was unprecedented political violence, as seven people were killed during the election and its aftermath. The Electoral Commission announced the result of the presidential election with several mathematical and computational errors, and changed the figures several times. The National Democratic Congress party and its candidate, former President John Dramani Mahama, challenged the result of the 12-candidate race, arguing that incumbent President Nana Addo Dankwa Akufo-Addo was wrongfully declared winner when he did not meet the constitutional requirement for a win, 50 percent of the vote plus one. But what caused the mess? The answer is simple: President Akufo-Addo has turned Ghana into a democratic dictatorship. In this wide-ranging cover story, Osei Boateng explores some of the elements that are enabling the democratic dictatorship, and the mess that happened during the elections.

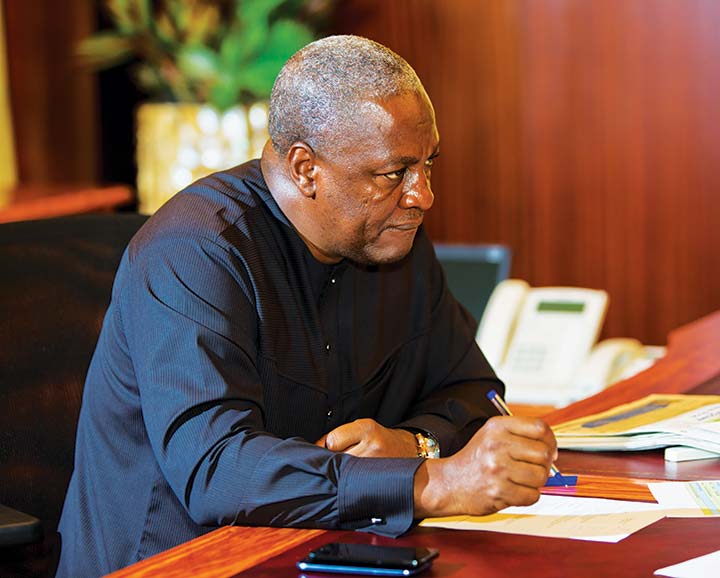

Ghana’s Electoral Commission (EC) is an experienced and competent national institution. Its budget for the 2020 election year came to more than GH¢1.06 billion, about US$181 million. Before 2020, it had run seven successive elections that were largely successful, increasing its reputation for integrity. Yet in the December 2020 presidential and parliamentary elections, the eighth since Ghana’s Fourth Republic came into being in 1992, the EC reported results riddled with mathematical and computational errors – and, according to the defeated National Democratic Congress (NDC) candidate John Dramani Mahama, the EC declared incumbent President Nana Addo Dankwa Akufo-Addo the victor before it was certain he had satisfied the constitutional 50%+1 vote requirement.

The EC issued multiple sets of results and corrections in the days immediately after the polls closed on Dec. 7, declaring Akufo-Addo, the New Patriotic Party (NPP) candidate, the winner, with somewhere between 50.8% and 51.6% of the vote. However, EC chairperson Jean Mensa made the first declaration when there were still 128,000 votes not yet counted from one constituency – and it was still theoretically possible that Akufo-Addo’s total could fall below the 50% needed to avoid a runoff.

Many Ghanaians do not see much sense in how a credible national institution like the EC could suddenly become such a wreck. But the answer is simple: Those Ghanaians have not paid attention to the fact that since President Akufo-Addo took office on January 7, 2017, their nation has become a democratic dictatorship.

It is an oxymoron, isn’t it? But that is the reality in Ghana today, or has been the reality under the reign of President Akufo-Addo, the man who spent a good part of his political life fighting for human rights for Ghanaians during the brutal military reign of the late President Jerry Rawlings, before the nation returned to democratic rule in 1992.

What is a democratic dictatorship? Theoretically, it is a form of government that has a semblance or façade of democracy, but hiding behind it is a thick layer of dictatorship. All the so-called “democratic” institutions and conventions still exist: the executive, legislature, and judiciary; the other supporting national institutions such as the security services and ombudsman agencies; and the media and civil-society organizations, who collectively are supposed to be a check on the executive’s power.

But the executive branch – personified by the president and the people who make up the power behind his throne – finds extra-constitutional ways and means to manipulate or rig the other arms of state and civil-society institutions, and to deprive them of their independence.

The executive achieves this by buying them through appointments, benefits, and cash, or breaking them if they are unwilling to be bought. By this way, whatever the executive wants, lawful or unlawful, it gets. The supposedly independent institutions of government and society just cave in for the sake of their own survival or future prospects.

This has been the experience of Ghana under Akufo-Addo. He covertly and overtly set out to dominate the nation. First, because he wanted to be sure of re-election in December 2020, and second, to facilitate state capture by key members of his extended family and their cronies, who have been the power behind his throne.

The reality on the ground

Akufo-Addo has packed the Supreme Court and the lower levels of the court system with his appointees, who are giving the president’s opponents rough justice. Several judges in the country appear completely beholden to the president.

In Parliament, the huge majority enjoyed by Akufo-Addo’s NPP from January 2017 to December 2020 effectively turned it into a rubber stamp. Almost every bill, good or bad, sent over by Akufo-Addo’s government was approved. NPP MPs were scared to express any dissent for fear of their place in the party or political careers.

He has done the same with Ghana’s ombudsman institutions. Last year, the auditor general, Daniel Yaw Domelevo, was forced to go on an accumulated leave of 123 working days in bizarre circumstances because he was exposing too much corruption by top government officials. The special prosecutor, Martin A.B.K. Amidu, also resigned in November 2020, because of “political interference in the independence of his office” over corruption issues.

Specifically, Amidu charged that the government had sabotaged his investigation of the Agyapa Royalties Transaction, a futures deal concocted by Finance Minister Ken Ofori-Atta, Akufo-Addo’s cousin. It would have been launched on the London Stock Exchange, and would have enabled the president’s family to have unfettered access to national financial resources.

“It thus became abundantly clear to me that I cannot continue under your government as the SP in the performance of the functions of my office in preventing and fighting corruption and corruption-related offences,” Amidu bluntly told the president in his resignation letter. “The 64-page analysis of corruption and anti-corruption assessment report [on the Agyapa deal] disclosed several corruption and corruption-related offences in respect of which I intended to open full investigations as the SP. I cannot do that now after your political interference in the performance of the functions of the office.”

Establishing a special prosecutor’s office was one of the many promises Akufo-Addo made during the 2016 campaign, telling voters that it would investigate, prevent, and prosecute people engaged in corrupt practices. Yet when he finally set it up in February 2018 and appointed Amidu, a former minister of justice and attorney general, to lead it, Akufo-Addo made it impossible for the special prosecutor to exercise any independence.

Amidu said the president “had labored under the mistaken belief that I could hold the Office of the Special Prosecutor as [his] poodle,” adding that Akufo-Addo was “really the mother corruption serpent.”

Akufo-Addo’s government’s dictatorial attitude to the ombudsman institutions worried the former Danish ambassador to Ghana, Tove Degnbol, before the elections. “It is particularly sad,” she said in December 2019, “to see that certain public institutions are doing their utmost to put hindrances in the way of integrity institutions such as the Auditor-General’s Office and the Office of the Special Prosecutor on anti-corruption. As we are approaching an election year, the attacks against integrity institutions and individuals contributing to fight corruption seem to be on the increase. This is noted with a lot of concern by many in the international community.”

The nation’s central bank, the Bank of Ghana, has not been spared either. It has been used to kill indigenous banks that belonged to Akufo-Addo’s perceived political opponents. Akufo-Addo claims that the banks were “glorified Ponzi schemes” — although when he was in financial distress prior to becoming president, he went to one of them for a loan. And when Ofori-Atta found himself in a financial mess, after the state economic-crime office recommended in 2002 that he and his business partners should be prosecuted for defrauding the Social Security and National Insurance Trust in a dubious real-estate deal, he too went to one of those “glorified Ponzi schemes” for a loan.

The media cave in

Ghana used to have a vociferous and diligent media which fought against tyranny under the Rawlings military government, and continued to exert their independence after democracy was restored in 1992. But Akufo-Addo’s government captured most of them. By bribery, intimidation, and threats, the government and its hangers-on have managed to get the majority and the most important parts of Ghana’s multitudinous media outlets in their pocket.

Here again, the principle of “being bought or being broken” has worked. A lot of media houses and journalists have caved in to the blandishments thrown their way by Akufo-Addo’s government. As a result, the many government scandals that have happened in the past four years have been half-heartedly reported by the local media. By the time the 2020 election campaign began, most of the media outlets in the country firmly knew where their bread was buttered.

The sum of Ghana’s situation makes sad reading: If the government controls the executive, legislature, judiciary, ombudsman agencies, security services, the media, Electoral Commission, and the other state institutions, the nation has a veritable dictatorship on its hands, dressed up in the garb of democracy. But it is not democracy. It is democratic dictatorship!

His own EC

Akufo-Addo was already thinking about re-election within months after he took office. In June 2017, EC chairperson Charlotte Osei and her two deputies, Amadu Sulley and Georgina Opoku Amankwaa, were booted out of office. Akufo-Addo’s calculation was that with Osei, who was appointed by former President Mahama, in office, it would be difficult to gain re-election, or at the least, she would not agree to be manipulated.

Osei had declared Akufo-Addo president in December 2016 when he won the election fair and square, defeating Mahama. But he was not comfortable with her in office. He had to have his own person at the helm of the EC, someone he could easily bend to do his bidding. So he orchestrated her removal, allegedly for “misbehavior and incompetence” and “breaches of Ghana’s procurement laws.”

A month later, on July 23, 2017, Akufo-Addo appointed Jean Adukwei Mensa to replace Osei. Mensa had been the head of the Institute of Economic Affairs, an Accra-based think tank, and, some say, a closet NPP sympathizer.

Jean Mensa’s EC was a new breed. Its raison d’etre appeared to be to do everything possible to ensure Akufo-Addo’s re-election.

Thus, she obliged when Akufo-Addo and the NPP wanted a new voters’ register that would whittle down the number of NDC members who were eligible to vote in the 2020 elections, particularly in the Volta Region – an NDC stronghold, which is to the east of the Volta Lake and shares a border with Togo.

Despite the hue and cry raised against the new register, especially as it was being done in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, Mensa went ahead with it. The EC alleged that the old register was bloated with the names of non-Ghanaian voters – particularly Ewes from Togo who allegedly crossed over to vote in the Volta Region.

Akufo-Addo and the NPP had made the same accusations in 2016, but quickly forgot them when the results came in, with Akufo-Addo beating Mahama by about a million votes in the presidential election and the NPP getting a massive 169 seats in Parliament as against the NDC’s 106. But in the Volta Region, Mahama won more than 80% of the vote in 2016, with 629,000 votes to Akufo-Addo’s 135,000 – by far his largest margin anywhere in the country.

In 2020, the allegations of a bloated register came up again, and the government sent soldiers and police officers to the Volta Region, which is about two-thirds Ewe. They claimed it was to stop Ewe-speaking Togolese from crossing the border to register as voters in Ghana. Reports spoke of the soldiers and police officers assaulting and intimidating Ghanaian citizens with the aim of discouraging them from registering to vote, and thereby reducing the NDC numbers from the region.

Nana Akufo-Addo’s government covertly leaned on Jean Mensa’s EC to reject birth certificates as supporting documents for voter registration. They seem to hold the view that Ghanaian birth certificates can be bought by anybody, including Togolese, and therefore cannot be trusted. When the matter was put before the Supreme Court, it ruled for the EC that birth certificates could not be used to register as voters.

Instead, the Court pronounced that the new national ID card, called the Ghana Card, and the Ghana passport were to be legitimate supporting documents for voter registration – incidentally, both documents are issued on the basis of the production of a birth certificate. Eventually, about 17 million of the country’s 30.4 million population registered.

“Everything about this election was manipulated and we had a hostile referee [Jean Adukwei Mensa] who knew next to nothing about elections,” says Johnson Asiedu Nketia, the general secretary of the NDC for the past 16 years. “But we went in because the alternative of withdrawing would mean destroying Ghana’s democracy and disappointing the people. I have known Jean Mensah for close to 10 years before her appointment as the EC boss, and apart from her partisanship, she doesn’t have the capacity to run an institution like the Electoral Commission.”

EC’s embarrassing errors

In reporting the results of the 2020 elections, the EC made errors that appeared to show a sudden inability to do basic mathematics and percentages.

The EC first claimed, via Jean Mensa’s result declaration on December 9, that the total number of valid votes cast in the presidential poll was “13,434,574, representing 79% of the total registered voters.” But when the votes garnered by the 12 presidential candidates were added up, they came to only 97.7% of that total, not 100%.

The next day, the EC, whether it discovered the error by itself or somebody else had pointed it out, attempted to correct the mistake and yet made another. It then tried five more times to correct the figures, and still made more mistakes.

Was this because it had chosen speed over accuracy? The EC had historically announced election results within 72 hours after the polls closed, but before the 2020 elections, it proclaimed that it would announce them within 24 hours. In the end, 48 hours passed before Mensa made the announcement.

She started her result declaration by using God as a prop: “To God be all the glory, great things He has done, and greater things He will do,” she began. “I indicate that this is a historic election because this is the first time that the Election Day went by without major incidents and occurrences. It is no wonder that the BBC described this year’s election as ‘boring’ – a testament to the seamless, incident-free process that we witnessed.

“As a Commission, we thank the Almighty God for his faithfulness and for how far he has brought us,” she continued. “We recognize without a shadow of doubt, that we could not have come this far without Him. As Proverbs 21:31 states – ‘A horse is prepared for battle, but victory comes from God.’”

Mensa’s predecessors at the EC had never invoked God when announcing election results. She next turned to self- congratulation: “Today we have succeeded in reforming our entire Biometric Voter Management System, procuring and deploying robust equipment and devices including the Biometric Verification Devices, the biometric registration kits, a user-friendly software to govern the entire Biometric voter registration and verification system, and a brand-new data center amongst others — all of which went through an international competitive tendering process.”

She also lauded the new Biometric Voter Register, saying it “reflects unique individuals who are eligible to vote. With determination and focus, we were able to prepare a Register that recorded seventeen million and twenty-seven thousand, six hundred and forty-one (17,027,641) eligible voters, in just 38 days in the rainy season of Ghana. Thankfully, the just-ended election did not witness issues of missing names, misplacement of polling stations, among others.”

Voters all over the country, she said, “have testified to a pleasant and seamless experience at their respective polling stations. We must be proud that it took, in many instances, 3-5 minutes for the average voter to be verified and to vote. We must be proud that the usual hassle and struggle at polling stations, the long queues, the overcrowding, were all absent.”

And then she returned to God: “And to crown it all, we must be proud of the fact that 48 hours after the election, we have been able to declare the results of the 2020 presidential election. With hard work, focus, determination, and above all God’s help, we can do all things. Indeed, we can!”

A comedy of errors

Yet the figures she announced seemed to indicate less than divine mathematical ability and accuracy. Mensa told the nation that “at the end of the transparent, fair, orderly, timely and peaceful presidential election,” 13,434,574 votes had been cast, representing 79% of the total registered voters. Her speechwriter spelled it out for her as “13 Million 4 hundred and 34 thousand, 5 hundred and 74.”

She also declared that Akufo-Addo had garnered 6,730,413 votes, winning 51.3% of the total votes, again spelled out by her speechwriter.

But the next day, on December 10, the EC came back to announce that “the chairperson of the Electoral Commission inadvertently used 13,433,573 as the total valid votes cast. The total valid votes cast is 13,119,460. This does not change the percentages stated for each candidate and the declaration made by the chairperson.”

That was an error of more than 300,000 votes. Also, Mensa had not said in her result declaration on December 9 that the total valid votes cast was 13,433,573. She had said it was 13,434,574. The clarification statement also said she had announced Akufo-Addo’s total as 6,730,587 votes, 51.3% of the total cast — actually 174 more votes than the number she had given the day before.

The point that put the overall results into doubt was that Mensa said on December 9 that the election results she was declaring excluded those from the Techiman South Constituency in the central Bono East Region, with 128,018 voters, because they were “not ready because they are being contested. As such collation is not complete.”

But because Akufo-Addo was leading Mahama by 515,524 votes, Mensa continued, “even if we added the 128,018 to the results of the 2nd candidate [Mahama], it would not change the outcome of the presidential election. Hence our declaration of the 2020 results without that of Techiman South.”

“If we were to add the results from Techiman South Constituency, Nana Addo Dankwa Akufo-Addo would obtain 50.8% of the votes and John Dramani Mahama would obtain 47.873% of the votes,” she explained.

But she was wrong. It was still theoretically possible, however, that if Akufo-Addo lost Techiman South by an extreme landslide, his national total would fall below 50%. So, where did the EC get the figure of 51.3% for Akufo-Addo in its clarification statement on December 10 – when the Techiman South results had not been publicly declared because they were still being contested?

Mensa said in her result declaration that Mahama had garnered 6,214,889 votes. The EC’s clarification statement reduced that number slightly, to 6,213,182, and lowered his percentage to 47.359%.

What others saw

The Research and Grant Institute of Ghana (REGIG) in Accra reviewed the results and found that the total number of valid votes cast and their corresponding percentages presented by Jean Mensa on December 9 did not match. Akufo-Addo’s 6,730,413 votes should have given him 51.595%, while Mahama’s 6,214,889 votes should have given him 47.336%.

“The percentage of valid votes obtained by each presidential candidate given the total valid votes of 13,434,574 presented by the EC is inaccurate,” REGIG said. “The total number of valid votes cast obtained by the 12 presidential candidates is equal to 13,121,111. When compared with the EC’s supposed total valid votes cast of 13,434,574, there is a difference of 313,463 valid votes. In terms of percentage, this corresponds to 2.333%.”

Without those 313,463 votes included, REGIG said, the EC’s figures for the candidates’ percentages would add up to 100%. With them, it was only 97.7%. Including those ballots, it calculated that Akufo-Addo should have had 50.1%, based on his 6,730,413 tally, while Mahama should have had 46.26%, based on his tally of 6,214,889.

In trying to correct the first mistake, the EC issued a new valid votes total of 13,119,460. It adjusted the candidates’ votes and their percentages, giving Akufo-Addo 51.595% (from his 6,730,587 total votes), and Mahama 47.366% (from his 6,214,889 total votes). But 6,730,587 is actually 51.3% of 13,119,460.

The errors, REGIG noted, raised questions relating to the credibility of the presidential election result, particularly because they were “not limited to the total number of valid votes cast, but also the total number of valid votes obtained by each candidate and their corresponding percentages.

“What accounted for the gross computational error in the results declared by [Jean Mensa] on 9 December 2020?” REGIG asked. “Did the EC audit or verify the accuracy of the results prior to the declaration? How much due diligence was undertaken and by who? When did the EC notice the anomaly – before, during or after the declaration? How did some candidates get more votes in the revised results released by the EC while others got reduced votes?”

Interestingly, in its clarification announcement on December 10, the EC made the categorical statement that Jean Mensa had “inadvertently used 13,433,573 as the total valid votes cast. The total valid votes cast is 13,119,460.”

Any good English dictionary defines “inadvertently” as: “Without intention, accidentally.” But Mensa’s speechwriter had spelled out the figure for her in the speech, as “13 Million 4 hundred and 34 thousand, 5 hundred and 74,” and added the figure 13,434,574 in parentheses for further clarity. This has led many people to ask how “inadvertently” is “accidental” in the EC and Jean Mensa’s estimation.

Under Ghana’s electoral law, however, once the EC declares the presidential result, only the Supreme Court can overturn it.

Rejection of results

On December 10, John Mahama rejected what he called the “fictionalized results of a flawed election.”

In a televised national address, he said the NDC had gone into the 2020 elections with assurances from the EC and the relevant state actors that the elections would be conducted in an atmosphere free from fear, and that it would be fair, transparent, and credible.

“Unfortunately, that has not been the case,” Mahama regretted. “What we witnessed across the country from Monday, December 7, 2020, exposed a deliberate plan to manipulate and predetermine the results of the election in favor of the incumbent candidate, Nana Akufo-Addo, who, as so happens, controls all of the state resources and oversees the state’s institutions.

“Despite all of the ruling party’s inducements, use of monetary enticements, and other such schemes on a scale never before seen in this country, the good people of this country understood what was at stake, and it was clear, as the result of the votes that were legally cast that the National Democratic Congress won the presidential and parliamentary elections. No amount of trickery, sleight of hand, or obfuscation will erase that reality.”

Election violence

Ghana’s elections are normally policed by the Ghana Police Service. But Akufo-Addo brought in the military. On and after polling day, seven people, most of them NDC supporters, were killed by the military and the police, and 15 others were hospitalized with gunshot wounds.

“The use of the military in this election is unprecedented,” Mahama said in his national address. “Armed forces featured heavily as an intimidating measure to reverse election results, and they continue to be used in the same intimidating role to insist on recounts in areas in which the incumbent has lost whilst arm-twisting election officers during these supposed recounts. We will not accept anything short of a declaration of the legitimate results, which point to an NDC parliamentary majority.”

The most egregious of these shootings involved a national security officer from the Office of the President, Collins “Kola” Kwaku. Though not licensed to carry a gun, he shot five people on polling day, killing one, Ibrahim Abass, an NDC member who was at a collation center in western Accra.

Kola is one of the former NPP “vigilante boys” who were recruited into the security services by Akufo-Addo’s government because of their loyalty to the party and president.

Mahama called the results announced by the EC “flawed and discredited.”

“The chairperson of the EC, in less than 24 hours after her declaration, has admitted that she has made unacceptable errors, which go to the heart of the entire electoral process and cast deep doubt on the credibility of the announced outcome,” he said in his televised national address.

“The Electoral Commission of Ghana has never brought its credibility to this historic low at such a crucial moment of election result declaration,” Mahama continued. “In fact, the litany of irregularities and blatant attempts at rigging for a candidate is obvious and most embarrassing. Ghana has come too far in our democracy, in our transparency, and in our well-earned international reputation for free and fair and nonviolent elections, to find ourselves here.”

The NDC initially announced that it had won 142 seats in Parliament, four more than needed to become the majority party in the current 275-seat configuration of Parliament. But the NPP wrestled five of them away, in Techiman South, Sefwi Wiawso, Zabzugu, Tarkwa Nsuaem, and Essikado Ketan, from the NDC.

Mahama called that “a deliberate attempt … to steal and, thus, subvert the people’s verdict.”

“A closer look and detailed examination of the constituency-specific facts cast very dark clouds on our democracy,” he added.

In Techiman South, Mahama said, “the NDC won quite clearly.” But the military was called in, and in the ensuing scuffle, it shot and killed two people, while a third later died of injuries.

“Three Ghanaians who wanted nothing more than for their country to fulfill its promise of democracy have lost their lives – at the hands of the military that is meant to safeguard their rights as citizens,” Mahama said.

At Sefwi Wiawso, he said, the EC “declared the results without the contents of one ballot box being counted. The parties had agreed that an issue of alleged over-voting should be referred to the collation center to be resolved. The ballot box mysteriously disappeared en route to the collation center. Nevertheless, results were declared in favor of the NPP candidate.”

The NDC eventually won two other constituencies, Sene West and Upper Denkyira, where there were unresolved issues. At Sene West, Mahama said, “a ballot box was snatched, and the culprit apprehended. The seal of the NPP must have dislodged in the ensuing scuffle. Those of the NDC and the Electoral Commission were intact. However, the NPP would not allow the contents of the ballot box to be counted and added to the lot, because it would obviously favor the NDC.”

When the votes in that disputed ballot box were finally counted days later, the NDC candidate had 275 and the NPP nominee 148 – giving the NDC candidate a 16-vote victory out of more than 26,000 cast.

The final official parliamentary tally gave the NDC and the NPP 137 seats each. That put the balance of power in the hands of Andrew Amoako Asiamah, a former NPP MP from Fomena in the Ashanti Region who ran as an independent candidate. On December 16, he announced that he had opted to sit with the NPP, giving them a one-seat majority.

Fraud made simple

Part of the reason the EC committed embarrassing errors was that it eschewed the process of collating ballots that had served Ghana well in the seven elections since 1992, which made fraud difficult.

In the past, once the valid presidential and parliamentary votes cast at each polling station were counted, the totals were sent to the collating center in the constituency. After receiving the polling stations’ figures, the constituency collating center added them up, under the watchful eyes of party representatives. It would then announce the winner of the parliamentary race, and immediately send the figures for the presidential vote directly to the EC’s national collation center (strong room) in Accra, where another group of party representatives would supervise their vetting and confirmation by the EC, and certification by the EC chairperson. The presidential figures from all the constituencies in the country were then added up to get the national total.

For the 2020 elections, Jean Mensa’s EC decided to add another layer of collation at the regional level, without much consultation with the political parties.

This meant the regional collation centers added up the constituency figures and sent summarized regional tabulations to the EC in Accra, from which the national tally was collated, vetted, confirmed, and certified.

That change, however, eliminated a key protection against errors and fraud. In the past, the national tally came from the production of constituency results sent to Accra, backed by the primary data via what is called “pink sheets.” This time, the EC in Accra took its figures only from the regional collation centers, which did not have to send pink-sheet data to back up the figures they were sending to Accra.

That particularly increased the possibility of tampering with the figures at the regional collation centers.

“Not a single pink sheet from the constituencies supporting the bulk regional collation was provided [to the EC in Accra],” Mahama told the nation in his address on December 10. “This is in direct violation of Regulations 3 and 44 of the Public Elections Regulations, 2020. (C.I. 127). Little wonder that the EC chairperson managed to obtain a cumulative figure of more than 100%…. On account of this, my party is confident that what has happened is a violation of the law, a violation of due process, and therefore tantamount to an illegality.”

The NDC general secretary, Asiedu Nketia, added: “There was no need for regional collations at all. It was one of the schemes they used to rig this presidential election.”

Complaining was futile, said former NPP senior politician Dr. Charles Wereko-Brobby, because this major change “smeared” the election regulations “without much fanfare or discussion as to its merits and demerits … The obvious injury to the vetting, verification, and confirmation of totals in the EC strong room was fatal for two main reasons: Firstly, the so-called ‘strong room’ could no longer receive information directly from each and every constituency in the country, as had been the practice in all previous elections.”

Instead, Wereko-Brobby said, the strong room “was supplied with secondary regional summaries,” which, given the EC’s promise of results within 24 hours, “left very little time for the party representatives to vet and confirm the presidential tallies from all constituencies. It was simply trusting the regional tallies or dump them, since the EC chairperson had the power to override objections and go ahead to announce results.”

This, according to insiders, immobilized the EC strong room for much of Election Day, as the party representatives there had nothing to do for hours.

“With all the comic relief ‘tragedies of cocked-up arithmetic errors going on with the tabulation’ of already declared totals, Ghanaians are entitled to a rational and sensible answer to the question: ‘As Ghana does not choose its president via an electoral college system, why did the EC of Ghana decide to resort to regional tabulation this time to reach the outcome?’” Dr. Wereko-Brobby asked in an opinion piece widely published by the local media.

Traditionally in Ghana, there have been two types of election data. First, the pink-sheet figures or primary data, and second, the collated or processed figures known as “secondary data.” Since 1992, election results have been declared based on the collated figures, whose validity depends on the soundness of the processing mechanism that the EC applies to the pink-sheet figures. Thus, when there is a dispute, it is resolved by going back to the pink sheet figures.

This time, however, the EC did not want to depend on the pink sheets to resolve the problem of its changing figures at the national level. It just merely changed the tallies of the 12 presidential candidates on a whim, apportioned percentages to them, and announced them as the new totals for the candidates – six times in the two days after Mensa’s December 9 result declaration.

The NDC decided to audit the results by going back to the pink sheets. The audit threw up some interesting stories. At some polling stations, the EC had reduced Mahama’s votes and increased Akufo-Addo’s. At others, it increased both candidates’ votes, but with Akufo-Addo gaining far more than Mahama.

Go to court, go to court

While the NDC audit was going on, the party resorted to street demonstrations nationwide to drive home the point that the presidential election had been “rigged” for Akufo-Addo. They were largely peaceful, but police fired hot-water cannons at some of the protesters.

As the demonstrations intensified, NPP supporters began to taunt the NDC, and their skirmishes caused a lot of tension in the country. A section of the public, including the Peace Council, called on the NDC to allow peace to reign by stopping its street demonstrations, reminding the party of how violence could tip the nation into instability.

Other people disagreed with that attitude. “It seems some people still think peace means the absence of war,” said Prof. John Gatsi, a lecturer at the University of Cape Coast. “In terms of elections, [they think] the absence of demonstrations, calls for the right thing to be done, and inability to express emotional pain of proven theft of votes means peace. Since rejecting election outcomes is an important element of protecting our democracy if it is based on facts and evidence, we should be open and willing to listen and obtain the basis for the rejection rather than calling for peace when correcting the errors is the surest path to sustainable peace.”

Prof. Gatso continued: “We do not have angels in political parties, the Electoral Commission, and government. We should accept that mistakes can occur, and sometimes they may be intentional. That is why we must work together.”

Kofi Asamoah-Siaw, vice-presidential candidate of the tiny Progressive People’s Party, stated that peace could not be achieved without rendering justice to the aggrieved party.

“Peace is paramount, but we are forgetting about justice,” he said. “For peace to prevail, there must be justice. We cannot cheat people and ask them to pursue a path of peace when we have refused to give them justice.”

Some NDC members were suspicious of the calls to go to court. Two members of the party’s legal team, Abraham Amaliba and David Annan, publicly declared they had little confidence that the Supreme Court justices appointed by Akufo-Addo would render a fair decision.

“If you ask me,” Amaliba said, “I have no confidence in the Supreme Court. If I had my own way, I would advise that the party shouldn’t go to court at all, because the court as currently composed will not give us justice.”

Annan agreed, saying: “I do not have confidence in the justices at the Supreme Court because of the numerous appointments made by President Akufo-Addo to the bench.”

He then took a swipe at the Ghana Bar Association, for allowing Akufo-Addo to pack the judiciary system. “When John Mahama was appointing justices to the Supreme Court,” Annan said, “the Ghana Bar Association and other bodies stood against him and asked him to stop because they feared his influence over them. So why did these same bodies watch Akufo-Addo appoint all these justices?”

Mensa’s vacation

In the middle of all this, the EC announced that Mensa and its staff were going to take four weeks off from work.

On December 19, it posted a notice signed by its deputy chairman of corporate services, Dr. Bossman Asare, saying: “Following the successful and peaceful conduct of the 2020 Presidential and Parliamentary Elections, Management has decided that the Commission will break for Christmas and New Year on Wednesday, 23rd December 2020, and resume duty on Tuesday, 19th January 2021.”

The notice came at a time when the Ghana Police Service was seeking a court order to ban NDC members from demonstrating until January 10, 2021.

A group of six civil-society groups responded with outrage. “Given the current post-election context and the matters arising, some of which might require their attention, we find it unacceptable that the EC should be shutting down at this critical moment, and without any clarification to the public of the alternative arrangements that have been put in place,” they said in their statement.

With public disgust rising, the EC announced the next day that “the senior leadership and some key operational staff of the Commission will continue to work during the break.”

NDC in court

The NDC eventually filed a petition challenging the presidential result on December 30, 21 days after Election Day – the last day it could legally contest the election results.

Overall, the EC’s litany of errors gave vent to NDC feelings that the presidential result had been rigged. In the petition, Mahama seized upon Jean Mensa’s pronouncement that the outstanding Techiman South constituency votes had been excluded from the national tally because it would not change the outcome of the presidential election.

According to Mahama, if all of Techiman South’s 128,018 total votes were added to his total, the total national votes announced by Jean Mensa on December 9 would increase to 13,562,592, and Mahama’s total would go up to 6,342,907. With Akufo-Addo’s vote remaining at 6,730,413, that would yield a percentage of 49.625 for Akufo-Addo, while Mahama’s would be 46.768.

That would mean none of the 12 presidential candidates got the constitutionally required 50%+1 to win. Thus, Mahama argued, the Supreme Court should overturn the result announced by Mensa on December 9, order a run-off between him and Akufo-Addo, and grant an injunction restraining Akufo-Addo from acting as president.

The petition requested the Supreme Court to rule that Mensa’s declaration of Akufo-Addo as the winner “violated Article 63(3) of the 1992 Constitution, and is therefore unconstitutional, null and void, and of no effect whatsoever.” Article 63(3) states that: “A person shall not be elected as President of Ghana unless at the presidential election the number of votes cast in his favor is more than fifty per cent of the total number of valid votes cast at the election.”

It followed, Mahama argued, that in making the declaration, “Mensa violated the constitutional duty imposed on her by Articles 23 and 296(a) of the 1992 Constitution to be fair, candid, and reasonable”; that it “was made arbitrarily, capriciously, and with bias,” contrary to Article 296(b); and “without regard to due process of law,” as required under Articles 23 and 296(b).

The multitudinous errors in Mensa and the EC’s declarations and clarifications of the results, Mahama argued, were further reasons why a run-off election should be ordered.

Because Mensa had said before the elections that she would announce the results within 24 hours after the polls closed, the petition said, she would not listen to people raising legitimate concerns about errors in the data she was using to determine who won.

“Prior to her making the purported declaration, Jean Mensa had been notified by Mahama’s agents of certain material errors in the figures collated, and then refused to accept a letter written by the NDC to her, raising some of those concerns,” the former president’s petition stated.

“If Jean Mensa had determined in good faith that her declaration on December 9 was in error, her constitutional duty to be fair and candid required her, among other things, to acknowledge the error, set aside her erroneous declaration and proceed on the path to correcting her error, and respecting the rights of candidates to participate in the processes towards the making of such a declaration.”

Mahama’s petition also argued that there was “vote padding by the EC” in 32 constituencies in favor of Akufo Addo. “When the votes Akufo-Addo obtained in all polling stations as shown on their respective pink sheets in these 32 constituencies are aggregated, the resultant figure differs from the figure that was declared by the EC for Akufo-Addo as captured on the summary sheets of the respective constituencies,” it said. “They show that more votes were added to those of Akufo-Addo than he obtained.”

The petition was still pending as Africawatch went to press. But with the Supreme Court heavily packed with Akufo-Addo appointees, some say the outcome is a foregone conclusion.

Conclusion

Nana Akufo-Addo is known for the human-rights battles he fought against the military junta of Jerry Rawlings earlier in his political career. For such a man to turn Ghana into a democratic dictatorship where state institutions have lost their independence and can only dance to his tune, or jump through hoops to make sure that he retains power, is a huge indictment for someone who was once one of the human-rights champions of Ghana.

But the closeness of the 2020 presidential race and the NPP’s razor-thin majority in Parliament are signs of Akufo-Addo’s loss of public support. In 2016, he carried the Greater Accra region comfortably, defeating Mahama by about 136,000 votes out of more than 2.1 million cast. In 2020, Mahama carried Greater Accra by about 73,000 votes, out of almost 2.6 million cast.

Greater Accra has the most votes in the country, and it is the most cosmopolitan of Ghana’s 16 regions – so losing the vote there is significant.

The NPP also lost 32 seats in Parliament. In 2016, it won 169 seats, while the NDC got 106. In the new Parliament, the NPP and the NDC have 137 seats each, with the one independent siding with the NPP.

Professor Yaw Gyampo, the director of the Department of Political Science of the University of Ghana, says that the flaws in Akufo-Addo’s first term, apart from “banking inordinate hopes” on its free Senior High School program, were that “the NPP made and allowed too many mistakes.”

Those mistakes were numerous, he said, they included: “greed, arrogance and corruption on the part of some appointees in an over-bloated government, antagonism of civil society, the ousting of [Auditor General] Domelevo to the revulsion of [civil-society organizations] and anti-corruption crusaders, the politically infantile move of imposing parliamentary candidates on constituents, the low-standard disingenuous attempt at comparing achievements to a regime that the NPP had described as ‘incompetent’ and had been monumentally defeated in the previous elections, the last-minute quickie road asphalting in some urban and peri-urban communities, the implementation of COVID relief social interventions like free water and free electricity for a certain category of consumers that looked more like propaganda and vote-buying interventions rather than candid pro-poor initiatives, as well as the neglect of other key issues of concern to many Ghanaians.”

Were it not for “Ghana’s exceptionally strong democratic culture,” he concluded, “the litany of errors seen in this election as a result of these logistical weaknesses could have had dire consequences for the peace of the country.”

For now, democratic dictatorship will continue to hold sway. But with a hung parliament where the NPP and Akufo-Addo will need all their 137 MPs present in Parliament to vote on issues, perhaps Akufo-Addo, the new colossus of Ghanaian politics, will somehow learn to accommodate the views of others, and maybe ditch the cavalier attitude and pomposity he showed in his first term.

On the whole, it is sad that Akufo-Addo has turned Ghana into a democratic dictatorship. The mess that it created during the just-ended elections will make the days ahead quite interesting in this polarized West African nation.