Ghana’s Chief Justice Kwasi Anin-Yeboah has vehemently denied that he promised a man whose case was pending before the Supreme Court that he could deliver a “successful outcome” for a payment of US$5 million. But Akwasi Afrifa, the former lawyer for the man at the center of the allegation, Ogyeedom Obranu Kwesi Atta VI, insists that his client told him that the Chief Justice had asked for the bribe, and that $500,000 of it had already been paid. The allegation has set Ghana on fire. With both Ogyeedom and Anin-Yeboah pressing their denials, Africawatch has taken a close look at the chronology and the facts of the matter, and has found that there is strong circumstantial evidence that Chief Justice Anin-Yeboah might be neck-deep in the bribery scandal. But it is not likely President Nana Akufo-Addo will pursue the allegations, because the Chief Justice has been useful to the government in many ways. Osei Boateng reports.

Chief Justice Kwasi Anin-Yeboah is facing accusations that he asked for a US$5 million bribe to fix a decision at the Supreme Court. The man he allegedly asked to pay the bribe is Ogyeedom Obranu Kwesi Atta VI, a traditional chief from Gomoa Afransi in the Central Region of Ghana. Ogyeedom had won a US$16 million judgment in a lawsuit against the Ghana Telecommunication Company, but Vodafone, the English-based global mobile-phone corporation that now owns the company, is appealing that ruling at the Supreme Court.

The Chief Justice’s accuser is Ogyeedom’s former lawyer, Akwasi Afrifa, a popular attorney in Kumasi in the Ashanti Region. Ogyeedom had hired him as an additional solicitor to the lawyer who had conducted the case at the original trial in the High Court in Agona Swedru, in the Central Region.

On July 8, Afrifa told the General Legal Council, the national body that regulates the legal profession in Ghana, that in late July 2020, Ogyeedom had informed him that “friends of his who were highly connected politically” had taken him to see Anin-Yeboah, and the Chief Justice had agreed to help him win his case “on condition that he drops my good self as the lawyer handling the case for him and engage Akoto Ampaw Esq in my stead.”

“He further informed me that the Chief Justice had demanded a bribe of US$5,000,000 for a successful outcome to his case, and that he had already paid US$500,000 to the Chief Justice,” Afrifa wrote in a statement to the secretary of the GLC’s Disciplinary Committee.

Ogyeedom had filed a complaint against Afrifa with the GLC, alleging that the lawyer had taken $100,000 from him to bribe judges, but failed to spend it. He charged that Afrifa had refused to refund him $75,000 of it.

Justice Anin-Yeboah, however, is the chairperson of the GLC, whose 11 members include three other Supreme Court justices, the Attorney General and Minister of Justice, and the president of the Ghana Bar Association.

The Chief Justice and Ogyeedom have both vehemently denied the bribe allegation. They have also denied knowing each other or even having ever met. But a reliable source close to Jubilee House, the seat of Ghana’s government, has told Africawatch that the Chief Justice and Ogyeedom, whose tentacles go deep in the ruling New Patriotic Party (NPP), and another person once met President Nana Akufo-Addo on another matter.

“Whether the president would recall the meeting is another issue,” the source said. But whether the President recalls the meeting or not, the circumstantial evidence against the Chief Justice in the US$5 million bribery scandal is strong and lends credence to Afrifa’s allegations.

How it all started

A land dispute sparked the scandal. Ogyeedom had sued Vodafone, which acquired the Ghana Telecommunication Company in 2008, and the Lands Commission, claiming that the company had built a microwave transmitting station on land in his area without paying any compensation.

Vodafone had been granted the right to build the transmitter on a piece of land offered by the Lands Commission at Gomoa Afransi, the Central Region town where Ogyeedom is the traditional chief.

Ogyeedom disagreed, and issued a writ of summons against Vodafone and the Lands Commission seeking a declaration of title to the land, an order for recovery of possession, and special damages for trespassing and unlawful possession.

The Lands Commission said that it had granted a lease to Vodafone in good faith, in the belief that the land formed a part of the larger area, the Efutu and Gomoa Ajumako Lands, that had been vested in the government of Ghana in 1961 by reason of the Ghanaian Constitution’s “stool lands” principle – which legally recognizes “customary ownership” of land, but with the government empowered to collect revenue.

But later in the course of the proceedings in the High Court at Agona Swedru, the Lands Commission stated that upon examination of available records, it had come to the realization that the land in dispute was not state land, “as it falls outside the subject matter of the area covered by Executive Instrument 206,” the legal document that vested the Efutu and Gomoa Ajumako Lands in the hands of the government.

The High Court awarded Ogyeedom US$16 million from Vodafone. Vodafone appealed, but the Court of Appeal in Cape Coast dismissed it on June 11, 2019.

Dissatisfied, Vodafone appealed that ruling to the Supreme Court. On July 30, 2020, the Supreme Court granted it leave to adduce fresh evidence to demonstrate that the land in question had been acquired by the Government of Ghana by Executive Instrument 86 of June 7, 1969, under the State Lands Act of 1962 (Act 125). The company also said it had evidence that the government, as far back as October 6, 1969, had paid compensation for the land to Ogyeedom’s predecessor, Nana Obranu Gura II.

Ogyeedom then applied to the Supreme Court for leave to bring in fresh evidence that he argued would demonstrate that the signatures appearing on the receipts presented by Vodafone were not authentically those of Nana Obranu Gura II.

Ogyeedom versus his former lawyer

On March 1 of this year, Ogyeedom wrote to the GLC in Accra, asking it to help him retrieve US$75,000 he claimed he was owed by his former lawyer, Akwasi Afrifa.

In his petition, Ogyeedom alleged that Afrifa had taken $100,000 from him to bribe judges, but had misapplied the money. He claimed that when he asked for a refund, Afrifa had only given him $25,000, and had refused to pay the $75,000 balance.

According to Ogyeedom, a friend introduced him to Afrifa “in or about 2019,” when he was looking for a lawyer to represent him “partly at the Court of Appeal in Cape Coast and fully at the Supreme Court in Accra.” He said he eventually engaged Afrifa for a fee of GH¢300,000 (about $50,000), which he paid in full.

But, Ogyeedom said, Afrifa, in the course of handling the case, asked him for an additional $100,000 “to enable him to do some ways and means (gymnastics) on my case so that we obtain a favorable decision…. Although I believed in the strength of my case, I decided to give him the money based on the advice he gave me.”

Ogyeedom said he later realized from Afrifa’s “demeanor” that the lawyer did not use the money for the intended purpose, so he fired him and asked for a refund. Afrifa paid him $25,000, Ogyeedom said, but “all efforts to retrieve the balance has failed.”

Afrifa’s bombshell

The GLC sent Ogyeedom’s petition to Afrifa on July 7, as an attachment to a summons to appear before its Disciplinary Committee on July 15, to answer the allegations made against him in the petition.

Afrifa responded the next day. “Having perused the contents of the petition, I deem it fit and appropriate to respond in the manner respectfully set out below,” he wrote in a statement to the secretary of the GLC’s Disciplinary Committee on July 8. “In the first place, it is untrue that a fee of GH¢300,000 was agreed between me and the Petitioner [Ogyeedom]. The truth is that a fee of GH¢1,000,000 was agreed, out of which the Petitioner paid GH¢300,000 and undertook to settle the remainder later.”

He said that he had represented Ogyeedom in both the Court of Appeal in Cape Coast and the Supreme Court, and also performed other duties for him, particularly at the National House of Chiefs in Kumasi. He said that Ogyeedom “was so impressed and satisfied by my service that he even wanted to dispense with his substantive lawyer, but I told him that I did not come into the matter to supplant the lawyer, and that I will stop the conduct of the case if he dispenses with the substantive lawyer.”

Afrifa is said to be known for not “making frivolous and unguarded allegations; at least the life he has lived and his character do not portray a stray talker,” and he then dropped a bomb.

He told the GLC that “at the end of July 2020,” Ogyeedom told him that after a meeting set up by politically connected friends, Justice Anin-Yeboah had agreed to help him win his case against Vodafone, on the condition that he fire Afrifa as his lawyer and replace him with Akoto Ampaw.

Afrifa added that the Chief Justice had demanded a $5 million bribe, and that Ogyeedom said he had already paid $500,000 of it.

“He further indicated that he was hard-pressed to raise the remainder of the $5 million,” Afrifa wrote, “and so I should refund some of the GH¢300,000 paid to me as fees because he had, in line with the advice of the Chief Justice, engaged Akoto Ampaw Esq as solicitor to continue the case before the Supreme Court.”

Afrifa said he responded “out of a sense of dignity” that he would rather refund the entire GH¢300,000, as well as bearing the costs of air travel, hotel bills and other expenditures incurred in prosecuting his cases at Cape Coast and in Accra.

“We aggregated the GH¢300,000 paid to me as being the equivalent of US$50,000, which I was to refund to him without any timeline being indicated,” Afrifa told the GLC. “He said he wanted the payment in dollars because he was raising the remainder of the money to be paid to the Chief Justice, and that [the US] currency was his currency of choice.”

Afrifa said he had paid Ogyeedom $25,000, the first installment of the $50,000 refund they had agreed on Jan. 27, and that he subsequently paid another $15,000, making a total of $40,000.

“The outstanding amount that I have to refund to him is US$10,000,” Afrifa told the Disciplinary Committee. “I am ready, willing and able to make the said payment of US$10,000 when I appear before the Committee on the 15th of July.”

He “categorically” denied that Ogyeedom had given him the $100,000 to bribe judges, saying that he had never suggested that his then-client provide “any money whatsoever for what he cryptically describes in [his] petition as ‘ways and means (gymnastics).’ I certainly have not and will not collect or receive any such money from him.”

Afrifa also rejected Ogyeedom’s attempt to portray himself as “naïve” in legal proceedings as “doubly misleading and manifestly fabricated.” “The Petitioner is not a novice in legal matters,” he wrote. “He is an experienced litigant and at the moment has several cases pending in various courts.”

Ogyeedom, he continued, “is a shrewd and experienced businessman” who holds a master’s degree and is about to complete a law degree at the Lancashire Law School in the United Kingdom. He is also “vigorously pursuing paramountcy,” legal recognition in the highest category of traditional chiefs, for the stool he occupies, Afrifa added.

He also “holds himself as politically well-connected,” with his closest friends including Samuel Abu Jinapor, Minister of Lands and Natural Resources and former deputy chief of staff to President Nana Akufo-Addo, and Captain Koda, head of the president’s security detail. Ogyeedom, Afrifa argued, “has uninhibited access to the seat of government, where he claims to be a constant presence. Such a person does not need a hapless provincial lawyer like myself to assist him pay a bribe.”

Finally, Afrifa said, Ogyeedom told him that he had caused personnel at the National Intelligence Bureau to conduct a probe of Anin-Yeboah, which showed “that the Chief Justice was in the process of acquiring several properties at a posh residential area in Kumasi, and therefore needed the money urgently.”

Ogyeedom denies everything

Afrifa’s response to the GLC summons immediately ignited a political bonfire nationwide. On July 11, Ogyeedom issued a statement denying ever telling Afrifa that the Chief Justice had asked him for a bribe.

“I unequivocally deny all allegations of intended bribery or actual bribery of any judge, including the Chief Justice whom I have never met or known personally, apart from seeing him at a distance from the bench,” he said.

Ogyeedom reiterated that he had “never met the Chief Justice before or dealt with him directly or indirectly in official or private capacity, neither do I even know where he lives nor have his phone number to have communicated with him.”

In a statement to the GLC, Ogyeedom’s new lawyer, Alexander K.K. Abban, described Afrifa’s statement as “a pack of untruths designed to denigrate the person of the Chief Justice, against whom [Afrifa] has cultivated a deep-seated animosity, and collaterally calculated to court disaffection of the Supreme Court, particularly the Chief Justice, against our client, knowing very well that the case from which the petition arose is still pending before the Court.”

Abban said Ogyeedom insisted that he had had no conversation with Afrifa regarding Anin-Yeboah demanding a $5 million bribe, or that the Chief Justice had asked him to let Akoto Ampaw handle the case instead of Afrifa.

“We reject and condemn in no uncertain terms [Afrifa’s] allegations which seem to suggest obliquely that Mr. Akoto Ampaw, one of the finest lawyers in the country, is in league with the Chief Justice in an unholy alliance to pervert the course of justice,” Abban wrote. “It is unthinkable to suggest that a party who had succeeded in both the trial High Court and the Court of Appeal would be in a haste to pay a bribe to the Supreme Court to affirm the decision of the said two courts.”

Given that the award in dispute was US$16 million, Abban continued, “it will defy logic for the client to part with a whopping chunk of US$5 million to the Chief Justice to improve the petitioner’s chances at the Supreme Court.”

He said on September 6, 2020, Ogyeedom had actually filed a petition asking Anin-Yeboah to recuse himself from further hearing of his case, because the Chief Justice had made a prejudicial comment about it.

Abban said Ogyeedom did engage the services of Akoto Ampaw “of Akufo-Addo, Prempeh & Co.” in October 2020, to assume the conduct of his case at the Supreme Court. It was Ampaw, Ogyeedom said, who filed an application to adduce fresh evidence at the Court for him, after it had granted Vodafone the right to introduce fresh evidence.

On March 31, the Supreme Court ruled in Ogyeedom’s favor. “Instructively, the Chief Justice, the alleged expectant recipient of the bribe, dissented. Indeed, he was the only dissenting voice,” Abban pointedly stated.

“These events belie the assertion that [Ogyeedom] was instructed by the Chief Justice to dispense with the services of [Afrifa] and engage Akoto Ampaw to create a fertile ground for the bribery plot to be executed. The dissent of the Chief Justice in the ruling of the Court on the application brought by [Ogyeedom] also tells a story contrary to [Afrifa’s] assertion,” he added.

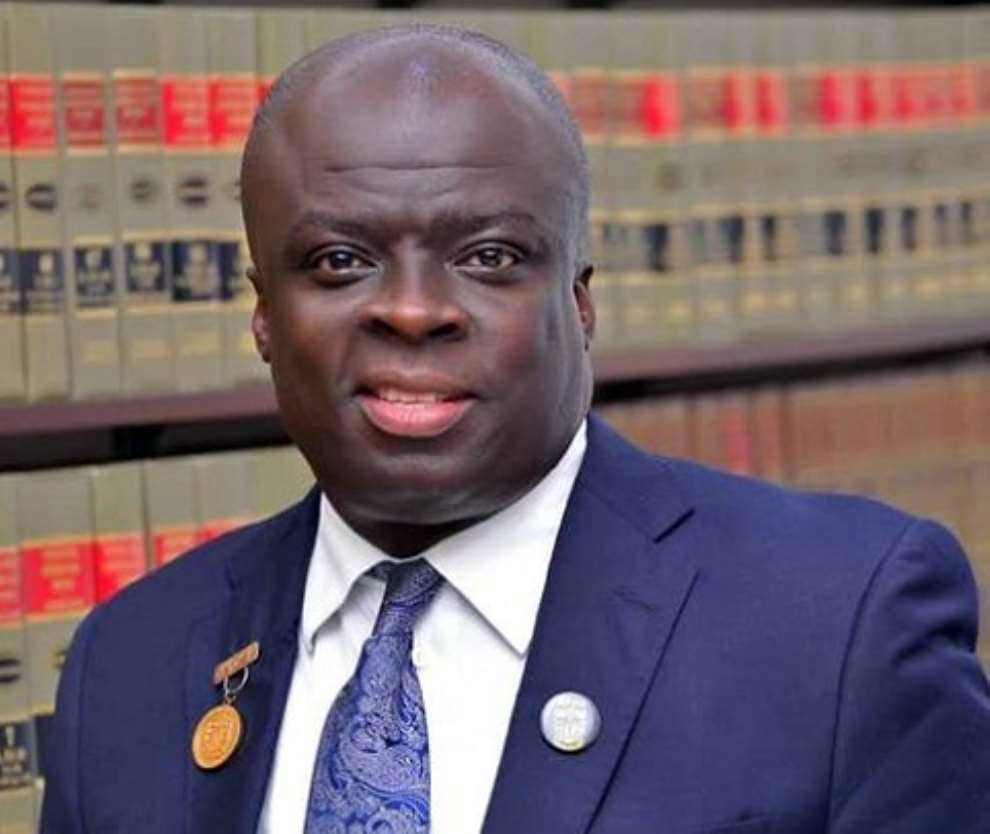

Anin-Yeboah’s rise

Chief Justice Anin-Yeboah’s legal career started at Koforidua in the Eastern Region, where he became a partner of the Afisem Chambers. His star started to rise in 2002, when President John Agyekum Kufuor, the first NPP president to take the party from opposition into government in 2000, made him a High Court judge. Kufuor moved him up to the Appeal Court a year later, and appointed him to the Supreme Court in 2008.

In December 2019, President Akufo-Addo nominated Anin-Yeboah as Chief Justice, to replace Justice Sophia Akuffo.

Anin-Yeboah instructed Judicial Secretary Cynthia Addo, the General Legal Council’s secretary, to ask the Criminal Investigations Department and the GLC’s Disciplinary Committee to conduct investigations into the bribery allegations.

Justice Addo, who Akufo-Addo appointed to the Court of Appeal in August 2020, said the Chief Justice “is saddened that without any shred of evidence, his name has been dragged into this sordid and potentially criminal matter.”

She claimed that the Anin-Yeboah “does not know” Ogyeedom and “has not met or seen him anywhere, except in the courtroom when he rises to announce his name when his case is called.”

Critically, Justice Addo said the Chief Justice “has not demanded or received any money from any person to influence any decision in this matter or any other matter. Indeed, the records show that [Ogyeedom] unsuccessfully petitioned for the recusal of the Chief Justice and Justice Victor Dotse from the matter, on a claim that they were prejudiced against him.”

The NPP-lawyer connection

Akoto Ampaw, the lawyer Ogyeedom hired to replace Akwasi Afrifa, is a partner in Akufo-Addo, Prempeh & Co, President Akufo-Addo’s law firm before he was elected president in 2016. Ampaw’s legal career and fortunes have hugely blossomed since then.

On the surface, Akufo-Addo now has little or nothing or to do with the firm, located at 67 Kojo Thompson Road, in central Accra’s Adabraka neighborhood. But over the last five years, Akufo-Addo, Prempeh & Co. has become the legal equivalent of what Finance Minister Ken Ofori-Atta’s Databank is to government financial business. It handles major domestic legal contracts, while a lot of investors and businessmen coming into the country go through it for their legal matters.

The mere fact that the President was a former partner in the firm brings a lot of business, both international and domestic, to Akoto Ampaw.

Generally, however, Ampaw avoids publicly associating his law practice with Akufo-Addo. He has had his own official letterhead printed in his own name showing him as a “legal practitioner and notary public,” operating from 67 Kojo Thompson Road. Only those who recognize that address can tell his business connections with the President.

On July 19, using his personal letterhead, Ampaw responded to Akwasi Afrifa’s July 8 counter-petition to the GLC with an attack on Afrifa’s reputation. “What, by way, is the track record of professional integrity of Lawyer Afrifa?” he asked. “These are, in my view, valid questions we must ask before rushing into taking his allegations seriously.”

In 2017, the GLC suspended Afrifa’s law license for four years, after he was found guilty of three instances of acting against the interests of his clients, by representing other clients with the same interests. His detractors have been pointing to that suspension as evidence that “he is not credible.”

“Lawyer Afrifa must have his own diabolical reasons for trying to implicate me in this crazy judicial bribery scandal, which manifestly does not add up. That is his problem,” Ampaw wrote.

“What I know as the facts are the following: Some time at the end of July 2020, Ogyeedom came to see me at our offices at Kojo Thompson Road, Adabraka, Accra, with a request that he wanted me to take over the prosecution of his case in the Supreme Court. I indicated that it would be foolhardy on my part to take over a case before the Supreme Court that was to be heard in some two to three days’ time. I therefore urged him to still rely on his current legal team in the pending application and, if thereafter, he still wanted my professional services, I would be ready to hear him out,” Akoto Ampaw explained.

He continued that Ogyeedom had later returned to consult with him, and that “with much reluctance, I agreed to take up the brief, upon the very clear understanding that if he wanted me to take up the case because he thought I was politically connected or had friends within the judiciary, then he was at the wrong place, as I did not carry on my work as a lawyer by such dishonorable means.”

He said he has had to make similar caveats to many potential clients, “as, alas, these days, virtually everything seems to be for sale in our country and ethical standards have gone to the dogs. Fortunately, my junior, Nicholas Lenin Anane Agyei, was present in my office when I laid out this standard for my professional relationship with Ogyeedom, and he can testify to same.”

He filed a notice of change of lawyer with the Supreme Court sometime in October, he said, and has since appeared in the Court “on a few occasions in respect of the matter to move an application to adduce new evidence in response to the Court’s grant of an earlier application by the appellant to adduce new evidence.”

On March 31, the Supreme Court granted Ogyeedom’s application to introduce new evidence in a 4-1 ruling. “Incidentally, the Chief Justice, who, according to Lawyer Afrifa’s yarn, wanted me to be engaged as lawyer in the matter to facilitate an outcome favorable to my client, was the dissenting judge out of a panel of five,” Ampaw said. “The records are there for anyone to access, including the media.”

He emphasized “without any equivocation” that the only dealings he had ever had with the Chief Justice in the case had been in open court as Ogyeedom’s lawyer.

His lengthy statement, however, did not mention the name of his firm, Akufo-Addo, Prempeh & Co., although he repeatedly referred to “our offices at Kojo Thompson Road, Adabraka, Accra.”

The circumstantial evidence

A close look by Africawatch at the chronology of events and incidents and the facts of the entire matter shows that there is strong circumstantial evidence that Chief Justice Anin-Yeboah might be neck-deep in the alleged bribery scandal.

The open secret: By the end of July 2020, Akwasi Afrifa had started talking to his lawyer friends and others in Kumasi about the US$5 million bribe that he said Ogyeedom told him the Chief Justice had demanded. It quickly became an open secret in Kumasi, where officers of the National Intelligence Bureau picked it up and reported it to their Accra headquarters, which passed it on to the government in August 2020. Apparently, the Chief Justice was alerted to it, and to protect his reputation, the powers that be set in motion an elaborate damage-control scheme. One facet of it was Ogyeedom’s petition to the General Legal Council.

The GLC’s unusual speed: Ogyeedom’s petition, dated March 1, was received by the General Legal Council on March 25, and only four months elapsed before the GLC called the matter for a hearing. Petitions to the GLC normally take much longer to get a hearing. For example, Africawatch filed a petition in 2019 against an Accra-based lawyer, John Darko, whom it charged had mishandled its defense against a lawsuit by the late Flight Lt. Jerry Rawlings. The GLC did not call Africawatch’s petition for a hearing until July 15, 2021.

The question is: Who pushed Ogyeedom’s petition ahead of the hundreds of others already in the GLC system waiting for a hearing, and why? It would appear that the powers that be pulled strings to rush it so it could be used to discredit Afrifa, so that if the bribery allegations against Justice Anin-Yeboah came out, people would say his accuser was not credible.

Ogyeedom’s contradictions: Ogyeedom contradicted parts of his original petition in his comments on Afrifa’s July 8 response to the GLC’s summons for the July 15 Disciplinary Committee hearing.

“After giving him the money, I realized from his demeanor that he did not use the money for its intended purpose as advised, so I fired him from the case and asked him for a refund of the money but he has since refunded US$25,000, leaving a balance of US$75,000 due and owing to me,” Ogyeedom said in his petition to the GLC. But his reply to Afrifa’s July 8 statement, written by his new lawyer, Abban, said that Afrifa had in fact given Ogyeedom $40,000 in refunds, not $25,000, without any explanation of the $15,000 difference.

Abban also asserted that Ogyeedom “felt impelled” to dispense with Afrifa’s services on July 27, 2020, after Afrifa had “arrogantly engaged the Supreme Court in a banter which had the potential of courting disaffection” for his case. Yet in his petition to the GLC, Ogyeedom had categorically stated that he had fired Afrifa for failing to use the ‘gymnastics’ money “for its intended purpose”.

In another petition, filed on September 6, 2020 at the Supreme Court, Ogyeedom complained that on the previous July 30, “the last but one day of the legal year,” the Chief Justice had “insisted on proceeding with the matter and proceeded, even when we had informed the court that our lawyer had taken a decision that he could no longer continue as our counsel and we prayed for time to find a new lawyer.”

The recusal petition: In the September petition, filed as speculations about the bribery allegation were quietly spreading, Ogyeedom asked both Chief Justice Anin-Yeboah and Justice Victor J.M. Dotse to recuse themselves from further hearing of his case against Vodafone, because of “prejudicial comments” that he claimed both men had made about the case in the past.

One aspect of the case reached the top court in May 2018, when Vodafone tried to get back $4 million it had paid to Ogyeedom on the orders of the Court of Appeal, and both Anin-Yeboah and Dotse sat on the panel that heard the matter. Vodafone returned to the Supreme Court in 2019, attempting to reverse the whole judgment, based on new evidence it said it had discovered that the government had already paid compensation for the land in dispute to Ogyeedom’s predecessor.

Ogyeedom then wrote a “recusal petition” to the Chief Justice saying: “The elders of the Traditional Royal Family and myself have noted with disquiet certain occurrences and developments in respect of the matter since aspects of the case first came before the Supreme Court. These have raised very serious doubts in our minds whether my family will receive justice before the apex court of the land.”

In the May 2018 hearing, Ogyeedom said, “we recollect vividly” that Anin-Yeboah’s first comment was: ‘which village land could sell for as much as that sum of money?’ This comment has stayed with us for its prejudicial nature, in that we wondered how such a comment could be made at a time the court did not have all the facts before it.”

The recusal petition also argued that a comment made by Justice Dotse in another case “certainly suggests that the prejudice is deep-seated.”

“In a case involving the Board of Governors, Achimota School v Nii Ako Nortei II, Platinum Equities Limited, and the Lands Commission, given on 20th May 2020,” it said, Justice Dotse stated that the court had “found the suppression of vital evidence” by the Lands Commission, not only in that case but also in an unreported case from April 28 of that year: Ogyeedom Obranu Kwesi Atta VI v. Ghana Telecommunication Company Ltd. If Lands Commission officials had not suppressed that “vital and material evidence,” Dotse continued, it would have been put before the court for adjudication.

“This assertion of Justice Dotse clearly meant that even before the substantive matter is heard, a decision had already been reached in favor of [Vodafone] that there had been suppression of evidence,” the recusal petition said. “We therefore fear that we will not receive a fair trial where you [Anin-Yeboah] preside over the panel or Justice Dotse is part of the panel.”

That petition has become one of the two main defenses used by the Chief Justice and his surrogates since the news of the alleged bribery broke out.

“It is therefore surprising that [Ogyeedom] would turn around to tell Afrifa that he needed to pay a bribe to the very person [Chief Justice Anin-Yeboah] he was requesting his recusal from the case,” Ogyeedom’s new lawyer Abban said. “How was the Chief Justice going to influence the outcome of the case when he himself was being asked by the very party to recuse himself? These events clearly demonstrate that [Afrifa’s] story is not true.”

But was this petition part of the alibis that were prepared to save face for the Chief Justice in case the alleged bribery request became public knowledge? The main incident it cites, Anin-Yeboah allegedly saying “which village land could sell for as much as that sum of money?” happened on May 8, 2018. Why did Ogyeedom wait for more than two years to protest against it and to ask the Chief Justice to recuse himself? Were Justice Dotse’s allegedly prejudicial comments in the May 2020 ruling thrown in as a cover to defuse questions about that time lapse?

On October 1, 2020, Justice Dotse, who was the president of the panel in the May 2018 hearing, filed his response to the recusal petition. “I do not recall His Lordship the Chief Justice making the comments ascribed to him before he became Chief Justice as is being alleged,” he stated. “In any case, such a comment is entirely not prejudicial and has not been the basis of the decisions of the panel then and now.”

The Chief Justice has not directly denied nor confirmed that he made those comments.

A strange dissent: Since the news of the bribery scandal broke, Chief Justice Anin-Yeboah has used his dissent in the March 31 Supreme Court ruling on the Ogyeedom-Vodafone case as his major defense.

The Court ruled 4-1 in favor of allowing Ogyeedom to introduce new evidence, to counter the new evidence that its unanimous decision of July 30, 2020 had allowed Vodafone to introduce.

“Our duty is to hold the balance evenly between the parties,” the four justices in the majority – Justices E. Yonny Kulendi, M. Owusu, C. J. Honyenuga, and I. O. Tanko Amadu – wrote. “It will therefore be unfair and likely to occasion [Ogyeedom] a miscarriage of justice if after granting [Vodafone] leave to adduce fresh evidence, we turn around to deny [Ogyeedom] an equal opportunity to introduce new evidence in direct rebuttal of the fresh evidence [Vodafone] will introduce. The ends of justice and our duty to be fair will be better served by affording both parties an equal opportunity to adduce fresh evidence to ensure a fair hearing of the appeal.”

There was little or no case law in Ghanaian jurisprudence that could be used as precedents on the issue, the four judges noted.

“This is a novel application, in our rich line of judicial decisions on the abduction of fresh evidence on appeal, it is difficult to find precedents where a successful party to a judgment on appeal seeks leave to adduce fresh evidence to support the judgment in his favor,” they wrote. “This, however, does not preclude this Court from considering such an application on its merits.”

That argument echoed the late Supreme Court Justice Nicholas Yaw Boafo Adade’s cautioning the Ghanaian courts against relying too much on judicial precedents.

“Precedents are merely to help us think about cases before us,” Justice Adade stated, citing a ruling in Merchant Bank Ltd v. Ghana Prime Wood Ltd 1989- 1999. “We are in danger of substituting our thinking to be done for us and this is because the impression is being created that every case must have a precedent by which it should be decided. So rather than do some original thinking about the case, we first try to look for a deciding precedent and then proceed to push our case into the straight-jacket of the precedent.”

The four judges in the majority said that it was obvious that Ogyeedom “is apprehensive that unless he is given an opportunity to proffer further evidence to rebut the fresh evidence proposed to be introduced by his opponent, the sufficient, cogent, and credible evidence on which his favorable [High Court and Appeal Court] judgment stands may be dislodged, the judgment impaired and reversed to his loss.”

The ultimate question, they said, “is whether or not the land, the subject matter of dispute between the parties, was compulsorily acquired by the state and compensation paid.”

The Court had already granted leave to Vodafone to bring in fresh evidence to prove that the land in dispute is state land, “having been acquired by the Government of Ghana in 1969 and compensation duly paid to the predecessor of [Ogyeedom],” the four judges wrote. Those “two legs of evidence,” they continued, “will become a material part of the evidence on record that this Court will consider in determining the pending appeal.”

Meanwhile, they said, Ogyeedom “contends that he has contrasting evidence which shows that his predecessor never received any compensation and that the signatures on the receipts which [Vodafone] has been granted leave to tender as fresh evidence are not authentic signatures of his predecessor.”

If Ogyeedom were not allowed to introduce that evidence, they said, his “right to cross-examine [Vodafone] and/or its witnesses on the new evidence will be effectively limited. Needless to say, a refusal to grant the instant application, notwithstanding the circumstances of this case, will undermine a fair hearing of the appeal.”

“We are of the considered opinion that this is a proper instance where we ought to exercise our discretion in favor of [Ogyeedom] in the interest of justice,” they concluded.

“The absence of any precedent is no reason why the application ought to be refused. As the highest and final court of the land, it is not every legal issue that we can resolve on the basis of judicial precedent,” Justice I.O. Tanko Amadu explained in a concurring opinion.

“In my considered view, the rules and accepted principles of law established by this Court cannot be considered in the abstract without proper attention to and consideration given to the facts of each case. The facts as in the instant application are peculiarly material and fundamental and must assume a crucial role in the process of our decision. That is why this application ought to succeed and I too will grant same,” Justice Amadu added.

Surprisingly, Chief Justice Amin-Yeboah dissented, even though he had been part of the five-member panel that unanimously allowed Vodafone to introduce its new evidence.

He argued that “the Supreme Court, as the last appellate court, sparingly grants leave for adduction of fresh evidence on second appeal. I think we must do so when the evidence raises serious issues of facts which the appellant has discovered.”

He said he agreed with the majority’s analysis of the law, but said his concern was that allowing Ogyeedom, “who has repeatedly been adjudged victorious based on the evidence he provided,” to adduce fresh evidence on second appeal “would be tantamount to reopening of the whole case.”

“To allow a Respondent to a second appeal to adduce fresh evidence on the basis that the prospective exhibits to be relied on by the Appellant seeking to adduce fresh evidence are not authentic should not be a ground for the application,” the Chief Justice wrote.

“Adduction of fresh evidence entails evidence-in-chief and cross-examination of the party by the other counsel in the appeal. Counsel for the other side will certainly be allowed to also rebut the evidence as the normal trial court does. Justice demands parity of treatment and the Respondent in this appeal [Ogyeedom] certainly will have the opportunity to challenge any evidence which may not be authentic.”

An appeal, the Chief Justice argued, is “an application to an appellate court to ascertain whether the judgment of the lower court was in error.” But, he added, “the power conferred on appellate courts in adduction of fresh evidence is limited as appellate courts are bound by the record of proceedings from the lower court. If care is not taken, appellate courts will be opening the floodgates for such applications by Respondents to appeals pending for determination.”

One legal expert said that Chief Justice Anin-Yeboah’s dissent followed the letter of the law, not the spirit of the law – that is, “obeying the literal interpretation of the words of the law, but not necessarily the intent of those who wrote the law.”

Yet the Chief Justice was not so stringent about the letter of the law when he presided over the Court’s unanimous decision upholding Vodafone’s application to introduce new evidence. It was only when Ogyeedom wanted to equalize opportunities by asking the Court to let him introduce new evidence to counter Vodafone’s new evidence, that “the letter of the law” became important to the Chief Justice.

So, what was the Chief Justice quibbling about? Was he trying to create another alibi for himself, anticipating that the bribery scandal would break out? At the time of the ruling on March 31, Ogyeedom had already filed his petition to the GLC against Akwasi Afrifa.

Defending Anin-Yeboah, Judicial Secretary Addo said in her statement that “the records further show that the Chief Justice was the only judge on a panel who recently on 31 March 2021 dissented in an application at the instance of [Ogyeedom] in favor of the respondent, [Vodafone].”

But was Anin-Yeboah dissenting against an otherwise unanimous ruling in favor of Ogyeedom to show that he could not have taken a bribe from him?

Why a bribe is plausible: In defending the Chief Justice, one argument made by his surrogates and some government officials was best summarized by Ogyeedom’s lawyer, Abban, when he said: “It is unthinkable to suggest that a party who had succeeded in both the trial High Court and the Court of Appeal would be in a haste to pay a bribe to the Supreme Court to affirm the decision of the said two courts.”

But in his petition to the GLC, Ogyeedom had clearly stated that “Afrifa asked for US$100,000 to enable him to do some ways and means (gymnastics) on my case so that we obtain a favorable decision … Although I believed in the strength of my case, I decided to give him the money based on the advice he gave me.”

If Ogyeedom was prepared to pay bribes to Court of Appeal judges to obtain favorable decisions even though he believed in the strength of his case, why would it be “unthinkable” for him to do the same at the Supreme Court?

More importantly, the new evidence the Supreme Court will hear might lead to it reversing the lower courts’ rulings in favor of Ogyeedom. The Court allowed Vodafone to introduce fresh evidence that the company said would show that in 1969, the government had indeed paid compensation for the piece of land at the center of the dispute. And on November 25, 2019, Sulemana Mahama, who became executive secretary of the Lands Commission in August 2018, informed the top court in a sworn affidavit that some of his staff had suppressed that critical evidence.

Justice Dotse said that Mahama’s depositions were “very important and far- reaching,” and if proven, they “would constitute a denial for the reliefs [Ogyeedom] had been pursuing in the law courts.”

All of a sudden, Ogyeedom was seeing the judgment award of US$16 million given him by the High Court at Agona Swedru, which had been confirmed by the Appeal Court in Cape Coast, going up in smoke.

That would appear to contradict the argument that it would “defy logic” for Ogyeedom to pay $5 million to improve his chances of the Supreme Court upholding his $16 million award – particularly when it was the Chief Justice who had allegedly asked for the bribe. After all, losing the entire $16 million would be much worse than losing $5 million and getting to keep $11 million. “The mathematics was in Ogyeedom’s favor,” says a lawyer in Accra.

Further, the bribe allegation is plausible because Lawyer Afrifa had told the GLC that Ogyeedom had gone to see the Chief Justice for help “at the end of July 2020” – the meeting, facilitated by Ogyeedom’s politically connected friends, where according to Afrifa, Ogyeedom told him that Anin-Yeboah had asked for a $5 million bribe and that he also change his lawyer to Akoto Ampaw.

The Supreme Court ruled in favor of Vodafone’s application to adduce new evidence on July 30, 2020. Can the timing of this ruling and Ogyeedom’s meeting with the Chief Justice and the alleged bribe request be merely coincidental?

The fact that Ogyeedom did not go to any other lawyer but Ampaw “some time at the end of July 2020” when his case at the Supreme Court appeared to be collapsing would seem to lend credence to parts of Afrifa’s allegations.

Ogyeedom knew that Ampaw was a politically prominent lawyer with offices in Accra’s Adabraka neighborhood, but he chose to hire Joseph Sam as his attorney at first, and later Akwasi Afrifa. What really made him remember Akoto Ampaw at that crucial moment in July 2020?

When the case of Ogyeedom v. Vodafone and Lands Commission got back to the Supreme Court for the second time in 2019 and came up for hearing in 2020, Anin-Yeboah had become the Chief Justice, but was not on the panel hearing the case. He reconstituted the panel and put himself on it. Though it is his prerogative as Chief Justice to decide which of the top court’s judges will sit on which panels and can add himself to any panel, one may ask: “What was his particular interest in this case?”

Ghana reacts with outcry

Since the scandal of the alleged bribe broke, there has been a consistent chorus from individuals and civil-society organizations asking President Akufo-Addo to boot out the Chief Justice. The Accra-based Center for Ethnical Governance and Administration (CEGA) and the Alliance for Social Equity & Public Accountability (ASEPA), have been the leading voices in this crusade.

As the Chief Justice referred the matter to the Police Criminal Investigation Department (CID) and the General Legal Council for investigations, CEGA called on him to step aside while the investigations are being conducted, as Anin-Yeboah is also the chairman of the GLC.

The National Democratic Congress (NDC), the main opposition party, rejected the Chief Justice’s referral of the case to the CID and the GLC.

“The allegations made against the Chief Justice are very grave and rock the very foundations of the Judiciary, which is an indispensable and independent arm of government,” the NDC said. “Any suggestion that the head of such an institution has sought to compromise his office to undermine the integrity of the judgments made by the courts, warrants the most serious attention.

“Without taking sides or commenting on the merit or otherwise of the said allegations of bribery against the Chief Justice, we believe that an investigation by the Police CID would be woefully inadequate to assure the Ghanaian public that a thorough inquiry has been conducted into the matter,” the NDC added.

The CID’s handling of previous politically tinged scandals, the NDC said, had been “woeful, and therefore the magnitude and gravity of this matter calls for utmost transparency and confidence-building, which the CID cannot muster at the moment.”

At a July 13 press conference in Accra, addressed by the party’s general secretary, Johnson Asiedu Nketia, the NDC explained that though the allegations against the Chief Justice had a component of criminality, “it is in equal measure about alleged misconduct on the part of a judge, and as such it would ordinarily fall with-in the ambit of the Judicial Service to take steps to unravel the truth about this matter, and take disciplinary action if proven to be true.”

The difficulty, the NDC said, was that “disciplinary authority against judicial officers is vested in the Chief Justice under Section 18 of the Judicial Service Act.” But as the issue being investigated is alleged misconduct on his part as a Supreme Court judge, the party contended, Anin-Yeboah should step aside while the investigations by the Judicial Service are pending.

“The Chief Justice cannot be a judge in his own cause, hence cannot set up a committee to investigate allegations of misconduct against himself,” the NDC said. “Best practice would require that the Chief Justice steps aside temporarily until the matters are looked into and a clear outcome emerges and we believe this instance calls for such an action.”

According to the NDC, because of the “considerable public interest involved in this matter, another effective and transparent approach in the circumstance would be a full-blown public inquiry. This can be done by invoking Article 278 of the 1992 Constitution under which Parliament can, by a resolution, compel the President to set up a Commission of Inquiry to look into the matters at hand in a transparent manner and make a faithful determination thereof.”

Ghana’s Commission on Human Rights and Administrative Justice “would be better placed to conduct such a serious inquiry,” the NDC added, because it “has an enviable reputation of looking into similar cases of alleged corruption against highly placed state and government officials”.

The NDC seriously disagreed with the Chief Justice’s referral of the allegations to the General Legal Council’s Disciplinary Committee, “for the sole reason that it is an offshoot of a body chaired by the person at the center of these allegations – the Chief Justice. The likelihood of an impartial and balanced investigation by them into this matter would be quite minimal so long as the Chief Justice remains at post. We therefore believe that the GLC should stay its hands over this matter, pending the final determination of the issue by independent state organizations cloaked with requisite authority to do so.”

But the GLC has not stayed its hands. It issued nine counts of professional misconduct charges against Afrifa on July 29. But calling the accusations flimsy, Afrifa has counter-sued the GLC at the Accra High Court.

The government finally spoke about the matter on July 26, after weeks of saying nothing, when Nana Bediatuo Asante, secretary to the President, wrote to the ASEPA executive director Mensah Thompson. ASEPA had petitioned President Akufo-Addo to invoke Article 146 of the Constitution to remove the Chief Justice. Bediatuo Asante disclosed that the President had already started in that direction.

“The President of the Republic has, in accordance with Article 146 (6) of the Constitution, commenced the appropriate processes subsequent to being petitioned for the removal of the Chief Justice,” he wrote.

But many political analysts say Bediatuo Asante’s letter is just a ruse, and the government’s “appropriate processes” will lead to nothing, because Chief Justice Anin-Yeboah is useful, and has been useful, to the government and the NPP in many ways.

Normally, in the Accra High Court, a computer randomly selects which judge is assigned to a case. But the Chief Justice has the power to override that random selection by asking an Appeal Court judge to sit on a High Court case – highly advantageous if the government has an interest in that case.

For instance, after Akufo-Addo’s government spent GH¢11.7 billion (US$1.94 billion) to clean up the banking sector and collapsed nine banks and several financial institutions, it charged the major shareholders of some of the banks with stealing and money-laundering. Some people said it could have saved those banks for one-third of that cost, and others accused it of targeting banks owned by perceived members of the opposition. In the cases of William Ato Essien of Capital Bank, Prince Kofi Amoabeng of UT Bank, and Kwabena Duffuor of Unibank, Anin-Yeboah assigned judges who had recently been promoted by the president to the Court of Appeal to try the cases, instead of having them go to Accra High Court judges. Did they have any special expertise in financial crimes that the High Court judges didn’t have, or was it that the Chief Justice wanted the cases handled by judges who’d be grateful for being moved up?

Seven Supreme Court judges are scheduled to retire by 2024, and President Akufo-Addo will nominate their replacements. How likely is it that an Appeal Court judge who wants to rise to the nation’s top court will rule against the government when they’ve been personally selected to handle a politically sensitive case?

So it is not likely that the President would let Anin-Yeboah go in disgrace. Some sources have in fact told Africawatch that the government was behind the schemes to protect him.

In all the toing and froing, some pertinent questions still remain unanswered. For example, Why are the Chief Justice and Ogyeedom denying that they know each other? Perhaps the answer lies in what a psychologist once said: “When a big man lies, it means he is hiding something big.”

The alleged bribery scandal has pushed the judiciary to the fore in a country where much of the public is losing confidence in the executive and legislative branches. The judiciary was seen as a bit more reliable, though in 2015 a Ghanaian journalist caught about 30 superior and lower court judges and over 100 judicial officers on camera receiving bribes to influence judgments in Ghana’s courts. That scandal led to the suspension of 22 judges by the Judicial Council.

Anin-Yeboah’s robust denial in the scandal echoes claims by Nelson Mandela’s former wife, Winnie Mandela, while she was on trial on charges of kidnapping and assaulting four young black men in Soweto in 1988, one of whom, 14-year-old Stompie Seipei, was beaten to death by her vigilantes. She fervidly denied all involvement in the crime, so when South African Judge Michael Stegmann was sentencing her in May 1991, he told her: “Diligence in ignorance is the equivalent of knowledge.” (He sentenced her to six years in prison, but an appeals court reduced it to a $5,000 fine and a two-year suspended sentence, after finding that Winnie Mandela had been only an accessory “after the fact” to assault.)

In the end, despite the strong circumstantial evidence that Chief Justice Anin-Yeboah might have solicited the $5 million bribe from Ogyeedom, it is likely he will get away with it, just like other big men close to President Akufo-Addo who got themselves mired in corrupt deals got away with their crimes.

Nevertheless, the Chief Justice has been tarred by the scandal, and the trust the people have in him is broken.

Editor’s Note

As Africawatch predicted that despite the strong circumstantial evidence that the Ghanaian Chief Justice Kwasi Anin-Yeboah might have solicited a US$5 million bribe from a defendant with a case pending before the Supreme Court, it was likely that he would get away with it, much like other big men close to President Nana Akufo-Addo who got themselves mired in corrupt deals had.

He did. On August 20, Akufo-Addo issued what sounded like a court judgment dismissing the allegations against the Chief Justice. The president said they were “unmeritorious and unwarranted,” and based on hearsay.

President Akufo-Addo’s dismissal was in response to a petition by the Alliance for Social Equity & Public Accountability (ASEPA), a small civil-society group based in Accra, that he begin impeachment proceedings against Anin-Yeboah.

The president did not order an investigation of Akwasi Afrifa’s allegations. Instead, he issued an 11-page statement saying essentially that ASEPA’s petition had no legal standing. As the group’s request was based on what it had heard from Afrifa, and Afrifa’s statement was about what he had heard from Ogyeedom Obranu Kwesi Atta, Akufo-Addo held, it was therefore founded on hearsay and not valid evidence.

On narrow legal grounds, the president was right to dismiss the petition. As put forward by ASEPA’s short letter, the bribery allegation came to the group as third-hand.

But if the alleged bribe request actually happened, the only eyewitnesses would have been the chief justice and Ogyeedom, along with whatever intermediaries were involved. If the participants deny that it happened, then there can be no prima facie case that any third party can establish beyond hearsay.

That, however, does not close the door to investigating any allegations of corruption, using the state’s investigating resources. So why didn’t the president take a broader view of the allegation and order an investigation or set up a public inquiry into the facts and circumstances? Instead, he dismissed the allegation against the Chief Justice on legalistic grounds, based only on the legal validity of ASEPA’s petition.

Anin-Yeboah’s usefulness to the government has been unique since he took office, and it will take a lot of doing for the government to let him go, especially in disgrace. It is why Akufo-Addo had to take the narrow view of the law to let him off the hook, basing his ruling on the legal deficiencies in ASEPA’s petition, and not because the allegation against the chief justice was “unmeritorious and unwarranted.”

In fact, in allowing the chief justice to go scot free, Akufo-Addo was behaving to type. Since coming to office 5 years ago, he has overdone himself as a president who hears no evil, sees no evil, and acts on no evil perpetrated by his high officials. That has been his track record. To have acted against the chief justice, or even investigated the US$5 million bribery allegation, would have taken a giant leap in faith. Sadly, the president has proven that he does not possess any leap in faith, let alone a giant one.