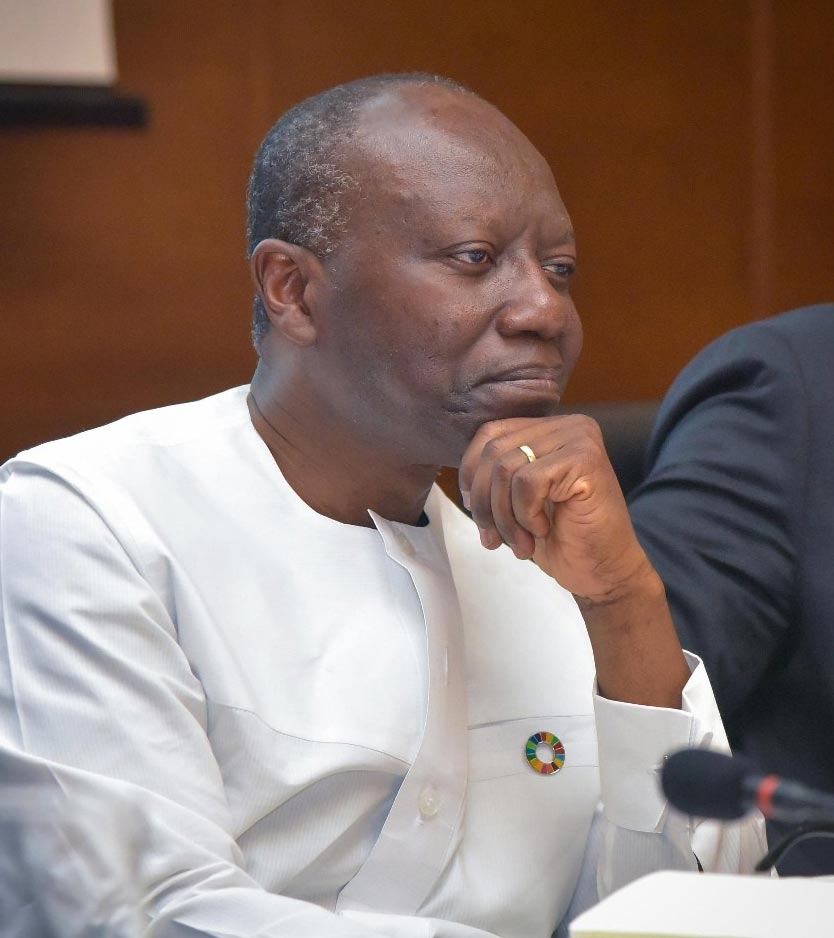

President Nana Akufo-Addo calls his cousin and finance minister, Ken Ofori-Atta, an economic “magician.” Before taking office in 2017, Ofori-Atta, an investment banker, built a business empire on a real-estate transaction with a state institution – a deal that one of Ghana’s own governmental criminal investigation agencies has deemed fraudulent. As finance minister, he has presided over a massive overhaul of the country’s banking system and wiped out most of the indigenous banks in the country in a very suspicious manner. Some say Ofori-Atta’s dark past makes him a man difficult to trust and even moreso when serious allegations that he is cooking the books are swirling around the government and throughout the country. Steve Mallory reports.

President Nana Akufo-Addo says Finance Minister Ken Ofori-Atta, his cousin, is so brilliant an economic leader that he has been “like a magician.” “He is amazingly capable,” Akufo-Addo told reporters at the Jubilee House (presidential palace) in the Ghanaian capital, Accra, last December. “He has been like a magician, having regard to where we were, and he has been able to find a way to raise money to do many of the things that we have been able to do. He has been a real brick and I am very satisfied with the work that he is doing.”

“He is not there because he is my cousin,” the President went on, lauding Ofori-Atta as “an investment banker in our country [who] built a successful business, and he is highly regarded in the world of finance and [in the] investment community here [in] Ghana and across the world. I believe he is doing a yeoman’s job for this country.”

Yet Ofori-Atta’s success as an investment banker came from a different kind of magic: The financial sleight of hand that enabled two of his companies, Databank Financial Services Limited and Enterprise Insurance Company Limited, to receive US$2.24 million from the Social Security and National Insurance Trust (SSNIT) as an investment in a dubious real-estate shell company – a deal that led to the Serious Fraud Office (SFO) recommending in 2002 that he and his business partner be prosecuted. Meanwhile, as Finance Minster over the past three years, Ofori-Atta has shut down nine banks and several financial institutions, some merely on the basis that their owners were members of opposition parties and he has also kept huge expenditures, debts and arrears off the books in order to make the nation’s budget deficit look smaller.

“I’m not presiding over a government of family and friends,” Akufo-Addo said. “Yes, one or two members of my family are in there. Mr. Ofori-Atta, who is the minister of finance, is my cousin. He happened to be the person responsible for the NPP [the ruling New Patriotic Party] fundraising drive. Nobody made any criticism of him when he was in that position, and I don’t think that it is so difficult for somebody who has been the fundraiser to transition to a finance minister.”

Most people don’t give a hoot about who a political party picks to raise funds for its activities but they are very much concerned about the credibility and integrity of who becomes their nation’s finance minister.

Early Beginnings

Many myths have been created about how Ofori-Atta and Keli Gadzekpo, his friend and business partner, became successful. One is that they arrived from the United States where they had gone to study and work, with nothing much in their pockets, but by dint of a few dollars loaned or given to Ofori-Atta by his businessman father, they rose like a colossus, and in a matter of a few years became large investment bankers.

Ofori-Atta, Gadzekpo, and a few others founded Databank in 1990, and it became the majority shareholder in Enterprise Insurance. “In reality, we started with zero, but after about nine or so months, getting to a year, we at least were able to talk one of the money-market firms in the country into giving us a 90-day promissory note because things just continued to be very, very tight,” Gadzekpo who is now the chief executive officer of Enterprise Group recalled in a BBC interview in November 2011.

With that promissory note (for about US$25,000), the two friends began to build up Databank and Enterprise Insurance. “You can imagine that was a treadmill because every 90 days I was hearing from those guys: ‘Are you paying as you said?’” Gadzekpo told the BBC. “‘Oh, no, we’ll get back to you.’ We must have rolled over for close to a year or a year and a half.”

According to Gadzekpo, to get Databank going, he and Ofori-Atta decided not to pay themselves a salary. “We focused on paying what few employees we had at the time,” he said. “We started, I think, with two or three guys and one lady… but we didn’t pay ourselves for probably a year and a half to two years.”

He did not mention their benefactor and point man in the National Democratic Congress (NDC) government: the late Victor Selormey, who was deputy minister of finance under then-President Jerry Rawlings. Selormey helped Ofori-Atta and Gadzekpo to get a number of government contracts and deals for Databank and Enterprise Insurance.

One of them was a sole-sourced transaction to offload a US$25 million package of government shares in seven listed companies. Databank, which ran the deal, hugely benefited. It subsequently benefited from more government transactions, including advising the Rawlings government on various privatization deals, one of which was the sale to the French bank, Société Génerale, of the government’s 52% (US$21 million) stake in the Social Security Bank. Ofori-Atta was influential in this deal.

Selormey was sentenced to eight years in prison in 2003 for a US$400,000.00 fraud, during then-President John Kufuor’s crackdown on corruption. He was released for health reasons in 2005, and died shortly afterwards.

Databank and Enterprise Insurance’s breakthrough, however, appears to have come from the Social Security and National Insurance Trust scheme in 1999. In 2002, the Serious Fraud Office (whose functions have since been taken over by the Economic and Organized Crime Office) recommended that both Ofori-Atta and Gadzekpo be prosecuted for fraud.

Shady dealings

President Kufuor’s NPP government had been in office for just one year. Brimming with fire and sulfur, as is the wont of new governments in Ghana, it instituted a general investigation into corruption in state institutions. One of these was the SSNIT.

The Ofori-Atta-SSNIT fraud made up Chapter 3 of the SFO’s report, and was headlined: Briefs on Identified Cases of Improprieties. The first brief involved Obotan Developers Limited.

According to the report, an undated Investor Participation Memorandum from Databank and a letter dated Dec. 10, 1998 from Enterprise Insurance showed that SSNIT had been invited to invest in a real-estate deal in Accra, buying a 3.5- acre parcel of land along Ring Road East between Independence Avenue and Osu Avenue (now Julius Nyerere Road) for US$3.5 million. The property contained the Massilia House at No. 3 Osu Avenue and three smaller houses.

The proposed host company for the real estate deal was Obotan Developers Limited, supposedly owned by Ofori-Atta and Gadzekpo and others via Databank and Enterprise Insurance Company. The proposed shareholding structure of the deal was given as Enterprise Insurance owning 45%, a $1.8 million equity; SSNIT 40%, $1.6 million in equity; and 7.5% each ($300,000 equity) for Home Finance Company and Social Security Bank Investments Limited.

However, on Feb. 16, 1999, the Board of Directors of SSNIT decided to acquire a majority shareholding interest of 55% in the project. On Feb. 26, Ofori-Atta, then Databank’s executive chairman, sent SSNIT director general Charles Asare a letter on Databank letterhead asking him to make payments of shares of Obotan into an escrow account established at Enterprise Insurance Company Limited.

“The reason why Databank Company Limited, which is not a shareholder in Obotan, requested SSNIT to pay the money (SSNIT’s shares) into EIC [Enterprise Insurance Company] account is difficult to comprehend,” the SFO report said.

Ofori-Atta was using Databank letterhead for Obotan business because at this stage, Obotan Developers Limited only existed on paper. It had not been registered as a company and so had no bank accounts.

“Consequently, on the advice of the Board (ref. letter dated 26th February 1999 from the Solicitor Secretary to the General Manager of Investment and Development), SSNIT paid US$2.244m to Enterprise Insurance Company Limited,” the SFO report noted. “The amount was disbursed as follows: Cost of shares (55%) US$2.2m. Subscription commission of 2% to EIC [Enterprise Insurance Company] US$0.044m. [US$44,000.00]”

At the time, Ofori-Atta and Gadzekpo owned majority shares in Databank and Databank was majority shareholder of Enterprise Insurance. They charged SSNIT a US$44,000.00 fee in favor of Enterprise Insurance, even though SSNIT had not bought any shares in Enterprise. The only relationship that SSNIT had with Enterprise Insurance was that both companies were shareholders in Obotan.

On that Feb. 26, the SFO report said, SSNIT issued an Agricultural Development Bank check for ¢5,385,600,000 (in old cedis, then US$2,244,000) to Enterprise Insurance to cover the 55% shares.

A Certificate of Incorporation and a Certificate to Commence Business were both issued for Obotan in March 1999, but were not delivered to the SSNIT Investments Department until March 29, 2001, via a memorandum from the company’s Solicitor Secretary.

But as of 2002, the SFO report said, “SSNIT has not been issued with any Share Certificate yet. At the time SSNIT paid the money, the company [Obotan] only existed on paper. There are no records to show that any evaluation was conducted by SSNIT to assess the viability of Obotan before SSNIT entered into the Joint Venture. And the relatively short period of time within which the project idea got crystallized into a Joint Venture (10 December 1998 to 26 February 1999) is quite discomforting.”

More shenanigans

In a message faxed to Emmanuel A. Gyamfi of SSNIT Investments on March 15, 2001, Obotan Company Secretary Ekow Awoonor stated that EIC had paid ¢4,161, 600,000 (US$1.7m) for 42.5% of the shares; SSNIT ¢5,385,600,000 (US$2.2m) for 55% of the shares; and SSB Investments nothing for 2.5% of the shares.

It turned out that Enterprise Insurance had not paid a single cedi for the Obotan shares, and yet it had been allocated 42.5% of them.

The SFO also said Obotan’s declaration that it had paid US$3.5 million for the Osu Avenue property was false. “The offer price of US$3.5m for a maximum of 3.5 acres appears highly uncompetitive,” it said. “Indeed, our independent investigations have revealed that the property was sold by CFAO to Obotan Developers for US$1,650,000, even though the agreement covering it put the sales value at ¢300,000,000 (US$125,000).”

All four houses on the site were occupied, it noted. The two on the Independence Avenue side of the property were occupied by an Italian and a Russian, the third by a Nigerian, and the Massilia House by officials from Databank Limited. But the Statement of Affairs received from the Company Secretary “showed no rental income” – only utility bills totaling ¢22,796,717.00

“The question is who is receiving rental income on behalf of Obotan, and why is Obotan bearing expenses on utilities?” the report asked. “The available records do not show who the bankers of the company [Obotan] are. Enterprise Insurance Company Limited (EIC) does not show evidence of payment for its shares of US$1.7m. SSB Investments has not paid its subscription of US$100,000, but it is still considered a shareholder of the company [Obotan] with a representation on the Board. Mr. Ekow Awoonor representing SSB Investments is the Director/Secretary of Obotan Developers Limited.”

In other words, SSB had not paid a cedi for its shares, but it still had a representative on Obotan’s board who was acting as the company’s director/secretary. The reason was that Ofori-Atta was using SSB as a sweetener to SSNIT to cover the fact that Enterprise Insurance had also not paid anything for its alleged shares in Obotan.

The SSNIT case officer for Obotan stated that the company’s registered offices were in the Enterprise Insurance building, the report continued, but “our investigation has revealed that Obotan Developers has no office in the Enterprise Insurance building as claimed by the case officer and other officers of SSNIT. Mr. Dan Seddon, one of the first directors of Obotan Developers Limited (the other being Mr. Emmanuel Asiedu Gyamfi of SSNIT Investments) has also given conflicting information on the number of shares acquired by Enterprise Insurance Company Limited.”

Seddon’s version, it continued, was that EIC was to have only 5% equity interest in Obotan, and it did not and has still not paid any money for its shares. “He [was] also not aware of the bankers and bank account of Obotan Developers Limited.”

So under Ofori-Atta’s watch, Obotan had no offices anywhere in the country, yet it received US$2,244,000.00 of SSNIT money as payment for shares in a company that did not exist. That money went to Enterprise Insurance, owned by Ofori-Atta and Gadzekpo’s Databank, which used it to do its own business and kept the profits.

In May 1999, the SFO said, “SSNIT requested for monthly management accounts for the purpose of effective monitoring.” But Ofori-Atta and Gadzekpo could not comply, because “there were no accounts available.”

But “in a letter purported to have been written on 23rd November 2000, but received on 26th February 2001, Enterprise Insurance Company Limited expressed its willingness to buy out the Trust from the [Joint] Venture,” the SFO said. It described the EIC action as “a curious development indeed,” and questioned whether it was not a grand design by Ofori-Atta and Gadzekpo to “bury the whole transaction” to avoid it exploding in their faces.

Scammers at work

The Serious Fraud Office concluded that the US$2.244 million SSNIT paid was “more than enough” to buy the Osu Avenue property from CFAO. “Thus, in our estimation, SSNIT money was collected and used to pay for the property plus allowances, commission, and legal fees to so-called promoters [Ofori-Atta and Gadzekpo] who were also members of the Company [Obotan]. Thereafter SSNIT was allocated just 55% shareholding, and others who did not contribute a dime, i.e., Enterprise Insurance Company and Social Security Bank Investments were allocated 42.5% and 2.5% respectively.”

That payment included a US$44,000.00 brokerage fee to Enterprise Insurance. “We are indeed at a loss to what service was rendered by Enterprise Insurance Company to SSNIT in the acquisition of the CFAO property to warrant the payment of such a fee,” the report said. “Our investigations indicate that the other shareholders – Enterprise Insurance Company and the Social Security Bank Investments – have as yet not contributed a dime towards the project. Finally, it must be noted that Databank Limited is the majority shareholder in Enterprise Insurance Company.”

In the end, the Serious Fraud Office recommended that: “The promoters of the project, Enterprise Insurance, Databank [i.e., Ken Ofori-Atta and Keli Gadzekpo], and Awunor Law Consultancy should all be prosecuted for deceiving SSNIT into a Joint Venture on Massilia House, i.e., presentation of false information on: (1) The cost of the Massilia House property and enticing SSNIT to release money for a project which at the time did not exist and which as at now does not even have a registered office; [and] (2) Presenting incorrect information on the contribution of Enterprise Insurance Company towards the project when in actual fact EIC as at now has not contributed one cent towards the project.”

Dark history

Ofori-Atta and Gadzekpo, however, were not prosecuted. The governing New Patriotic Party’s Akyem faction (who are now in power) put pressure on President Kufuor not to press charges against them. The Serious Fraud Office’s report then disappeared into obscurity as Ofori-Atta and Gadzekpo’s businesses grew into an empire. They own interests in insurance, retail banking, private equity, microfinance, pharmaceuticals, and real estate across Africa.

Ofori-Atta and Gadzekpo have flatly denied the fraud accusations. “Contrary to false and malicious media reports, the Obotan Project was a credible development project and each of the stakeholders was determined to make the project a success,” Ofori-Atta said in a statement to the press in November 2014. “There is no basis whatsoever for alleging that the project was any kind of fraud.”

He said that SSNIT’s board had met and agreed to participate in the Obotan Project, subject to obtaining 55 percent of shares, and that Obotan Development Limited had been incorporated in 1999, during Jerry Rawlings’ NDC administration.

“SSNIT was not defrauded of their investment in any shape or form,” Ofori-Atta insisted. “In fact, SSNIT’s equity in the Obotan Project was subsequently purchased by Databank when it transpired that SSNIT was not going to be in a position to continue in their role in the Project. The reason for this is that from 2000 onwards, SSNIT became beleaguered by allegations and investigations into their portfolio of investments.”

Databank, he said, bought out SSNIT’s investment under an agreement dated August 31, 2005, with payments made from June 2004 to February 2007. It paid SSNIT US$2,224,000.00 – the dollar equivalent of the cedi value paid by SSNIT in 1999 – as subscription and commission for its shares, and an additional US$78,680.00 as interest.

“SSNIT got back every pesewa (or cent) it invested in the Obotan Project, plus interest,” Ofori-Atta said. “There is no evidential basis for any allegation of fraud in connection with the project.”

But with the NDC then in power, under President John Dramani Mahama, Ofori-Atta said that he would “not be surprised that I could be arrested” in order to further the government’s “malicious campaign” against him.

The mathematics of Databank’s buyout of SSNIT is highly interesting. In 1999, SSNIT paid Enterprise Insurance (by extension Databank) US$2,244,000.00 and it refunded the full sum in 2007, with US$78,680.00 in interest added.

Thus, for the eight years that Enterprise Insurance used SSNIT’s money to do its own business and kept the profits, it paid an average of about US$820.00 a month in interest – an annual rate of 0.44%. Where in the world does anybody get such a favorable interest rate for borrowing more than US$2 million for eight years? In the eight-year period of the buyout, between 2002 and 2009, Ghana’s national interest rate averaged 17.93%. It reached an all-time high of 27.5% in March 2003 and fell to an all-time low of 12.5% in December 2006. So for Ofori-Atta and Gadzekpo to pay only a mere 0.44% interest on state funds totaling US$2.2 million that they had schemed out of SSNIT and then held on to for eight long years is simply preposterous, which leaves this case wide open for possible prosecution by any government in the future.

Killing the banks

In 2017, under Ofori-Atta’s watch as finance minister, the Bank of Ghana embarked on what it called a cleanup of the banking and Specialized Deposit Institutions sector. Nine banks, 23 savings and loan companies, and 386 microfinance firms, most of them indigenous financial institutions, were affected.

The nine banks that went under the knife were the UT Bank, Royal Bank, Heritage Bank, Capital Bank, Beige Bank, uniBank, Construction Bank, Sovereign Bank and Premium Bank.

Five of them, Royal Bank, Beige Bank, uinBank, Construction Bank, and Sovereign Bank, were hurriedly brought together under a new bank called the Consolidated Bank of Ghana (CBG) to, according to the government, save depositors from losing their money. The CBG was incorporated, issued a license by the governor of the Bank of Ghana, and had its officials approved by the central bank all in just one day, Aug. 1, 2018. The government rushed all that through without following the proper legal procedures.

According to Ofori-Atta, the government has so far spent GH¢12.125 billion on the banking-sector cleanup. “The government set up the Consolidated Bank Ghana Limited and capitalized it with GH¢450 million to ensure that no depositor lost deposits,” he told Parliament in his 2019 midyear fiscal policy review and supplementary estimate.

“The government of Ghana has had to issue bonds to the tune of GH¢11.2 billion to cover the cost of the financial sector re-solution and protect depositors,” he continued. “The government has [also] provided an amount of GH¢925 million in cash to cover the small depositors of the 386 microfinance institutions, bringing the total cost to GH¢12.125 billion.”

However, despite the GH¢925 million supposedly provided, depositors of the closed savings and loans and microfinance companies were generally given a mere GH¢20,000.00 (US$3,600.00) at the maximum, and some could not access even that.

Then President Akufo-Addo, in his State of the Nation Address to Parliament in February, promised that “all depositors of the savings and loans and microfinance institutions, including DKM which collapsed in 2015, would receive 100% of their deposits once the validation exercise was concluded.”

Later, the Consolidated Bank of Ghana confirmed that the government had made available GH¢1 billion in cash and GH¢4 billion in bonds to settle payments to depositors of the collapsed financial institutions.

Repaying depositors was still limited, however. The bank opened new accounts for depositors “whose claims have been validated and accepted by the Receiver for payment based on data released to CBG by the Receiver.” If the customer’s fund exceeded the cash payment threshold, CBG opened two accounts, one operational account and another, an investment account to hold non-interest bearing bonds for five years for the entity, and withdrawals would be allowed in 10 equal instalments every six months beginning March 31, 2021.

CBG started making cash payments on Feb. 24, and by the end of March, it claimed to have disbursed about GH¢920 million but it is not clear what the current cash payment threshold is. Some depositors have expressed strong objections to the government holding part of their funds in non- interest bearing bonds for them against their will.

Meanwhile, the government has so far not been able to recover any substantial amount of the depositors’ funds that have been locked up due to the closure of the banks and financial institutions.

“The Receivers have been able to make some recoveries,” Bank of Ghana Governor Dr. Ernest Addison said in January. “They are not as impressive as we had expected. The last time I checked, about GH¢1.4 billion cedis has been recovered … Now we’re looking at the loan portfolio of these banks that were resolved, of over GH¢16 billion, so out of the GH¢16 billion, if you’ve recovered just GH¢1.4 billion, it tells you that there’s a lot of work more to be done. Yes, the effort is there, but the progress, however, in terms of the amount of cedis they’re recovering, is slow.”

Who is telling the truth?

The capital shortfall in the banks that the government closed down was about GH¢5 billion. When Ofori-Atta was asked whether it would have been better to save the banks than to kill them, considering that the almost GH¢20 billion it has cost to shut them down was about four times the amount needed to save them, he answered: “The state at which the current administration found the banking and SDI sectors, it was too late to salvage the already comatose financial institutions, and intensive and intrusive surgery was required for the many walking dead.”

But the founder of the defunct Capital Bank, William Ato Essien, told a local TV station that both Ofori-Atta and Gadzekpo had approached him about buying the bank the year before the Bank of Ghana declared it insolvent.

“If the bank was that bad,” he said, “would the current finance minister and the board chairman of Enterprise Insurance, Keli Gadzekpo, come to my office to say ‘we are interested to buy Capital Bank?’ Ken Ofori-Atta came to my office in 2016 to make that proposal.”

Perhaps Capital Bank could have been saved or fixed, but Ofori-Atta and Gadzekpo would not give Ato Essien the chance to try. In October 2019, he and three others were charged with misappropriating about GH¢260 million from the bank. Ato Essien pleaded not guilty and has denied any wrongdoing.

Indeed some of the closed financial institutions were poorly run and were already on the verge of collapse.

However, some people believe that the closure of others, particularly Heritage Bank, uniBank and GN (Groupe Nduom) Savings and Loans was politically motivated. Two of the majority shareholders of the three financial institutions – Seidu Agongo of Heritage Bank, and Dr. Kwabena Duffuor of uniBank – were members of the main opposition National Democratic Congress (NDC), while Dr. Papa Kwesi Nduom of GN Savings and Loans belonged to the opposition Progressive People’s Party (PPP).

“I don’t understand the issue [of Heritage Bank] because the chairman of the board [was] Dr. Kwesi Botchwey,” says Prince Kofi Amoabeng, a co-founder of the defunct UT Bank, who has been hauled before a court with 5 others over the collapse his bank. “I have a lot of respect for him when it comes to finance in this country and managing boards. He will not, in my estimation, ever accept to be a chairman of a bank that is not right and dealing in all sorts of things.”

Amoabeng called it “extremely odd” for anyone to say that the owner of a bank that had Dr. Botchwey as board chairman didn’t have what it took to hold that responsibility. “I mean the owner doesn’t run the bank himself, he’s a Ghanaian, he has got money, he has appointed the right people to run the bank for him, so what is the excuse? I find that extremely unfair,” he said, a tinge of sadness in his voice. “Maybe I don’t have all the facts, but from where I stand, I find it really unfortunate.”

Heritage Bank’s license was withdrawn by the Bank of Ghana on January 4, 2019. The central bank’s governor, Dr. Addison, said that Agongo was “not fit and proper” to own a bank because he was standing trial in an Accra High Court for alleged shady business deals with the Ghana Cocoa Board (COCOBOD), the main administrator of the country’s cocoa industry.

“We don’t need the court’s decision to take the decisions that we have taken,” Dr. Addison replied when asked by journalists if it was not premature to close down the Heritage Bank before Agongo’s case had been decided by the court. “We have to be sure of the sources of capital to license a bank. If we have any doubt, if we feel that it’s suspicious, just on the basis of that, we find that [it] is not acceptable as capital. We don’t need the court to decide for us whether anybody is ‘fit and proper.’ Just being involved in a case that involves a criminal procedure makes you not fit and proper.”

“[But] since when has suspicion become a substitute for credible evidence?” a be-wildered Agongo responded. He called the decision to close his bank “capricious, arrogant, malicious, and in bad faith.”

“The central bank obviously had little regard for the time-honored principle that a person is presumed innocent until proven guilty by a court of competent jurisdiction. The fact that I have a case pending before the High Court is a matter of public knowledge, but my guilt or innocence is yet to be determined by the Honorable Court,” Agongo said in a statement. “The determination that I am not a fit and proper person to be a significant shareholder of Heritage Bank because the central bank suspects the funds are derived from illicit or suspicious contracts with COCOBOD, is not only calculated to prejudge the outcome of the criminal proceedings but also violative of the principle of presumption of innocence to which every individual is entitled.”

Dr. Botchwey agreed. In defense of Agongo, he said in a statement: “Heritage Bank was, by Bank of Ghana’s own admission, a solvent bank. It never received liquidity support from the Bank of Ghana. Its corporate governance record had never been impugned by the Bank of Ghana. We believe we have been done a grave injustice, and a terrible precedent set that does not bode well for the future.”

And with that, what people now call the “Addison Principle” came into force in the country. They describe it as a political scheme of using the alleged sins of individuals, regardless of whether the sins have been proven in a court of law or not, or whether those sins have any bearing on their businesses or not, to kill their companies. It is a very dangerous phenomenon that poses a clear and present danger to companies such as the Enterprise Group and Databank should the tables turn in the country as Ofori-Atta and Gadzekpo still have the SSNIT fraud allegations wrapped around their necks.

The uniBank closure

The closure of uniBank, a major indigenous bank, is one of the most bizarre episodes of Ofori-Atta’s cleanup of the banking sector.

According to Dr. Johnson Asiama, former second deputy governor of the Bank of Ghana, the central bank knew “in early 2016 that uniBank was experiencing persistent liquidity crisis and hence was borrowing heavily daily on the interbank market.”

He said uniBank applied to the Bank of Ghana for liquidity support for the first time in 2016. The bank “informed us that they were experiencing large withdrawals from key institutions such as COCOBOD, the Volta River Authority, the Ecobank Development Corporation, and Databank,” Dr. Asiama said in a statement.

On the other hand, he added, “we had information that uniBank had a number of government and government-related receivables totaling over GH¢1.3 billion, on account of its large exposure to the energy and construction sectors.”

Those who owed huge amounts of money to uniBank included the Ministry of Finance (Ofori-Atta’s ministry), the Road Fund, the Ghana Education Trust Fund (GETFUND), and COCOBOD.

An Assets Quality Review (AQR) by the Bank of Ghana had also revealed that uniBank was among four banks that had significant exposures to state-owned enterprises and bulk oil-distribution companies (BDCs) in the energy sector.

“UniBank and these other banks were thus borrowing heavily daily from other commercial banks and needed the Bank of Ghana’s liquidity support to keep them in operation,” Dr. Asiama said. “Total liquidity support from the Bank of Ghana, for example, increased steadily from GH¢200 million at the end of 2015 to over GH¢2.2 billion by the end of 2017.”

Upon assumption of office by the new governor [Dr. Addison in April 2017], Dr. Asiama said “I prompted him on the need to get the Minister of Finance [Ofori-Atta] to pay uniBank at least some part of their claims on the government. The Minister of Finance was actually invited to the Bank, based on my promptings to discuss these payments to uniBank, but he declined suggestions, on the grounds that uniBank had gotten enough [BOG liquidity] support to thrive.”

“Clearly, if at least part of these payments were done at the time, uniBank could have avoided the persistent daily clearing failures that eventually shut them out of the interbank money market,” Dr. Asiama stated.

Bad faith

Ofori-Atta’s refusal to pay what the government owed to uniBank or even part of it – including what his own Ministry of Finance owed – sealed the bank’s fate.

Not to pay uniBank its government receivables on the grounds that the bank had gotten enough liquidity support from the Bank of Ghana was wrong. It created the false impression that liquidity support by the central bank to uniBank was free money, whipping up public sentiments against the bank.

The plain truth is that the government owed the distressed uniBank about GH¢1.3 billion. The Bank of Ghana came to its aid with GH¢2.2 billion in emergency liquidity support, which was not free money, but a credit with a 26% interest rate. UniBank backed that up with GH¢650 million of its own treasury bills. Ironically, the central bank was paying only 14% interest for the treasury bills.

Adding the GH¢1.3 billion the government owed uniBank to the GH¢650 million in bonds comes to almost GH¢2 billion, so the government’s claim that uniBank was bankrupt and beyond rehabilitation cannot be true.

The Bank of Ghana then appointed Nii Amanor Dodoo of the Dutch international accounting firm KPMG as the official administrator of uniBank. He downgraded uniBank’s assets and declared it insolvent and beyond rehabilitation. Based on that, the Bank of Ghana withdrew uniBank’s license and immediately appointed the same Amanor Dodoo as the receiver.

That would appear to violate the Banking Act 930, which states, though ambiguously, that someone who occupies the position of official administrator of a bank cannot work at the same bank until at least two years later. That provision’s rationale is to prevent official administrators from presenting false reports on banks in order to take them over as receivers. UniBank claims that this is what happened in its case. The bank’s shareholders say KPMG’s Amanor Dodoo impaired about GH¢6.7 billion of uniBank’s total assets of about GH¢8.7 billion, and never discussed it with the management or the shareholders. Impairment, bankers say, can never be unilateral. But that is what uinBank shareholders claim Amanor Dodoo did with their bank.

Rough justice

Dr. Nduom tells a similar story in a lawsuit he and two others filed in an Accra High Court challenging the revocation of GN Savings and Loans’ license. He alleges that the Bank of Ghana, the finance minister, the attorney-General and the receiver [Eric Nana Nipah] all conspired to frustrate, thwart and destroy GN Savings and Loans. And that the decision to shut down his financial institution was “at best, reckless, fraught with stark malice and in self-evident violation of basic public law rules.”

Dr. Nduom states in court documents that “the Bank of Ghana and the minister of finance deliberately diminished or distorted the total indebtedness of the government and its MDAs [Ministries, Departments and Agencies] to the Groupe Nduom so as to enable the Bank of Ghana to revoke GN Savings’ license.”

The Bank of Ghana (BoG) “failed to conduct a true, fair and independent assessment of GN Savings’ books – matching the value of its total assets against the value of its total liabilities. And, indeed, if the BoG had conducted a proper, true, fair and independent audit into the books of GN Savings, it would have known or come to the obvious conclusion that GN Savings was solvent and, therefore, capable of meeting its debt obligations as at the time that the BoG revoked its operational license,” he says, adding that “not only did the BoG fail to take into account all GN Savings’ assets before concluding on its solvency, but also that there was a malicious design by the respondents between and among themselves to suppress the value of GN assets so as to enable them to come to the pre- determined conclusion that GN Savings was insolvent.”

GN Savings and Loans and uniBank were the two oldest indigenous financial service providers in the country. And whatever Ofori-Atta may say, the government’s cleanup destroyed almost all of Ghana’s indigenous financial institutions. They used to serve small businesses that would not be looked at by the big banks, especially the foreign-owned institutions. Thus, the cleanup has seriously damaged the prospects of a large sector of the Ghanaian economy, which now finds it difficult to get credit from the remaining big foreign banks.

In downtown Accra, indigenous Ghanaian entrepreneurs are now complaining bitterly about discrimination at the hands of the foreign banks.

Putting it in context

To understand and appreciate indigenous Ghanaian financial institutions, one has to go into their history. Two important state-owned institutions, the Bank of Ghana and the GCB Limited have their roots in the Bank of the Gold Coast, established by the British colonial government in 1953. Britain had sent a white banker to Ghana, then called the Gold Coast, to study the banking environment. His report re-commended that an indigenous bank should be established for the local people, because the foreign-owned banks discriminated against them.

That gave birth to the Bank of the Gold Coast which performed the dual functions of commercial banking and central banking. When Ghana became independent in 1957, those two functions were separated. The commercial-banking side became the Ghana Commercial Bank, now GCB Limited, and the central-banking part became the Bank of Ghana.

Some 70 years ago a British white man told Ghanaians that foreign banks were discriminating against them, so they should get their own indigenous bank. Now their own black man comes along and closes down almost all the indigenous banks. As Ghanaians say: “Did the nation go or did it come?”

Interestingly, while Finance Minister Ofori-Atta and Governor Addison were busy arbitrarily shutting down indigenous financial institutions in their banking sector cleanup, there were widespread speculation that some foreign banks in the country were engaged in money-laundering but the two men failed to deal with that financial menace and now the nation finds itself on the European Union’s money-laundering blacklist.

A bad own goal

The total cost of the banking-sector overhaul, according to Bloomberg News, now exceeds GH¢20 billion, “after the government also contributed GH¢800 million toward the recapitalization of some lenders, and another GH¢1.5 billion for investors in failed fund management companies.”

“It [the GH¢20 billion] has also added to Ghana’s debt, which the International Monetary Fund estimates reached 63% of gross domestic product by the end of 2019, up from 59% the year before,” Bloomberg News reported.

At a recent town hall meeting in Kumasi, Vice-President Dr. Mahamudu Bawumia defended the Bank of Ghana’s cleanup, saying it would strengthen the banking sector.

“Some have criticized the action of the central bank,” Bawumia said. “First of all, let us remember that the failures of financial institutions that we have witnessed recently were a direct result of a system of poor licensing, nonexistent capital, weak corporate governance characterized by related-party transactions, [and] political- influence peddling, among other things.”

Dr. Bawumia blamed “the NDC government and the previous management of the Bank of Ghana.” He claimed the NDC, in power from 2009 to 2016, “had ample time to address impending failures. They were aware of the problems in 2015 in the case of banks and as far back as 2012 … in the case of savings and loans and microfinance companies. Even in opposition, I alerted the country that on the basis of available data, [that] eight banks were likely to collapse, but they refused to act.”

That cannot be wholly true. Apart from individual factors, the general ailment that confronted Ghana’s entire banking system had to do with the macroeconomic difficulties the nation experienced in the recent past. One factor was the sharp fall in crude-oil prices, which impacted negatively the nation’s fiscal as well as current account. Another was the “dumsor,” the frequent rolling blackouts caused by Ghana’s in- adequate electricity supply. Both impaired the economy and depleted the nation’s international reserves.

Those challenges resulted in the accumulation of energy-related debts to the banking industry and of arrears in payments to contractors, setting off a wave of difficulties for the banking sector. The Energy Sector Levies Act, enacted by the John Mahama government in late 2015 to help address the energy-sector debts, is now bringing in about GH¢3.5 billion a year in revenue.

The former governor of Bank of Ghana, Dr. Abdul-Nashiru Issahaku also launched the Assets Quality Review program to ascertain the health of the entire banking sector and began work in early 2016 to update the regulatory framework, that resulted in the passage of the Bank of Ghana Amendment Act, the Banks and Savings Deposit Institutions Act 930, and Deposit Insurance Act 931.

Dr. Issahaku also introduced the Recapitalization and Liquidity Roadmap for the banking sector in September 2016, and established a new minimum capital requirement of GH¢230 million for banks. He intended to complete the banking sector’s recapitalization by the end of 2019 and to impose corrective actions in accordance with Act 930. But he did not have the chance, as he was replaced when the Akufo-Addo government took office in January 2017.

Issues arising

The high cost of the banking-sector reforms could have been avoided if Dr. Issahaku’s strategy had been continued.

And moreso Finance Minister Ofori-Atta could have used a sovereign guarantee to support the seven-year and ten-year corporate bonds issued under the Energy Sector Levies Act, to clear all the GH¢10 billion debt owed to banks in Ghana and the bulk oil distributors. It would have been easy to raise that entire amount at once and relieve the banks early in 2017, which could have reversed the slide into insolvency for at least some of the liquidated banks.

The long delay in paying contractors who owed money to these banks also worsened matters for the banks that were hugely exposed and hence experienced severe deterioration in their portfolios.

In the case of the systemically important banks such as uniBank, the Financial Investments Trust, a subsidiary of the Bank of Ghana, could have been used more actively to contain the meltdown, instead of shutting them down in such a rush. The high costs of Finance Minister Ofori-Atta and Governor Addison’s banking-sector reforms have been largely self-inflicted, and a lot could have been done better through a more careful and patient resolution method.

As expected, the huge cost of the banking sector cleanup blew a bigger hole in the nation’s budget deficit for 2019 so Ofori-Atta craftily counted it and billions of cedis in payments to independent electric-power producers as a below the line expenditure not considered part of the deficit, by deeming them amortization – payments used to reduce a debt – but those liabilities directly added to the nation’s budget deficit, hence they cannot be treated as below the line. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) objected to Ofori-Atta’s suspicious accounting methods and after some encounters, the IMF and the government “agreed to disagree” on the nation’s fiscal deficit for 2019. Whereas Ofori-Atta concealed the financial sector and energy sector payments in the 2019 budget and put the fiscal deficit at 4.5% of gross domestic product, the IMF added them in their calculations to get a 7.5% fiscal deficit for Ghana for the same year 2019. And serious allegations that Ofori-Atta is cooking the books are swirling around the government and throughout the country.

Now Ghanaians are feeling the social and economic pains resulting from the harsh banking cleanup by the government, and some are now asking: How clean is Ofori-Atta himself? Such a disturbing question makes it difficult for people to trust the president’s economic “magician.”