William Ruto, once a roadside chicken-seller in the rural Rift Valley, took office as president in September after narrowly defeating Raila Odinga in the August election. The vote was not settled until the Supreme Court dismissed Odinga’s claims of fraud, but the post-election period was relatively peaceful. Now, can Ruto’s government deliver prosperity to the “hustler” workers he identified himself with?

William Ruto was sworn in as Kenya’s president on September 13 after narrowly winning the Aug. 9 election in East Africa’s most stable democracy. The former deputy president quickly signaled that his leadership would be a strongly Christian one.

The Supreme Court confirmed Ruto’s election in a unanimous ruling that dismissed eight petitions seeking to annul the result, including one submitted by the losing candidate, Raila Odinga. It found that some of the claims “were based on forged documents and ‘sensational information.’”

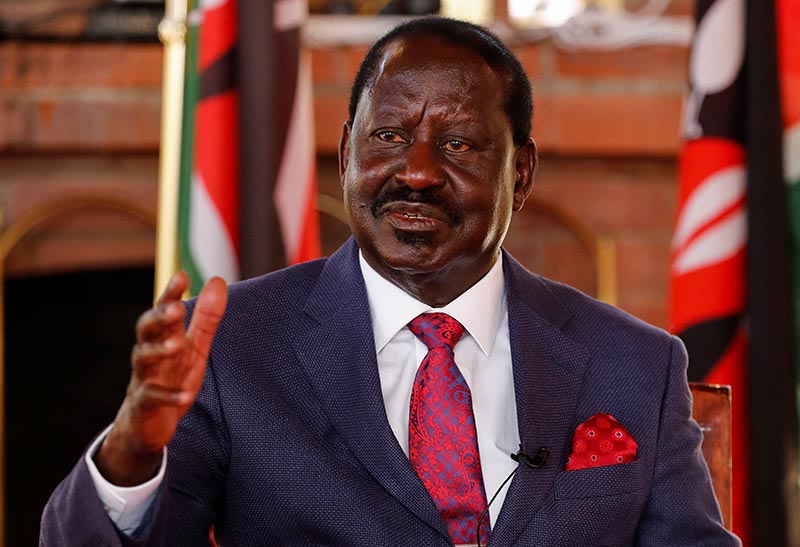

Odinga responded by saying that he had “respect for the opinion of the court.” But he said he “vehemently disagreed with the decision” and “would be communicating in the near future on our plans to continue our struggle for transparency, accountability, and democracy.”

The court ruling followed weeks of uncertainty which began with a six-day wait for the presidential outcome after a close race. On August 15, four Independent Elections and Boundaries Commission commissioners disowned as “opaque” the results about to be announced. But the electoral commission chairman, Wafula Chebukati, went ahead and declared that Ruto, of the Kenya Kwanza coalition, was the country’s president-elect with 50.5% of the popular vote. That put him about 230,000 votes ahead of Odinga, of the Azimio la Umoja coalition, who got 48.8%.

The governors, senators, and members of parliament elected were closely split between the two alliances. Kenya Kwanza won a 33-32 advantage in the Senate, with two unaffiliated members, while Azimio la Umoja had a 168-167 plurality in the National Assembly, with 14 independents.

Azimio la Umoja rejected the results and challenged Ruto’s election in the Supreme Court. It argued that some of the polling station-level forms (specifically 34A forms, which are used to report results) had been changed on the elections commission portal by hackers associated with Ruto; that Ruto had failed to secure the “50% plus one” majority needed for a first-round victory; and that the gubernatorial races in Kakamega and Mombasa counties had been postponed with the ulterior motive of reducing turnout in Odinga strongholds.

Many Kenyans feared the possibility of violence. But the campaigns and post-election period were relatively calm and peaceful. This was despite vigorously contested, close, disputed, and at times tense races.

Praying for ‘no revenge’

The 55-year-old Ruto had been the deputy to former President Uhuru Kenyatta, but the two had a bitter split that left them not speaking to each other for months at a time. On inauguration day, the audience cheered as the men shook hands, and again as Kenyatta handed over the instruments of power.

“There should be no revenge,” Bishop Mark Kariuki thundered at the ceremony, wearing a deep purple stole embroidered “PEACE.”

Ruto, who had dropped to his knees in tears and prayer when the court upheld his win, knelt on the stage minutes after his swearing-in during an extended sermon. “A chicken seller to a president,” intoned the pastor, highlighting Ruto’s humble youth.

His first Twitter post as president quoted Psalms: “This is the day the Lord has made; let us rejoice and be glad in it.”

The peaceful transfer of authority will burnish Kenya’s democratic credentials in a region where some leaders have held power for decades.

Nairobi’s 60,000-seat Kasarani Stadium was packed with Ruto supporters wearing his party’s colors of yellow and green. They danced and waved miniature national flags to the strains of a band.

“He is our fellow youth! I know he will bring us more opportunity,” said dancer Juma Dominic as he and his troupe warmed up.

The event began with some chaos. Scores of people were injured as they forced their way into the packed stadium. A medic said a fence fell down after people pushed it and at least 60 were injured. There were no reports of deaths.

With the transition, Kenya’s presidency moves from one leader indicted by the International Criminal Court to another. Both Kenyatta and Ruto were accused of orchestrating attacks in the deadly 2007 post-election violence, but the cases were closed amid allegations of witness intimidation.

Ruto’s campaign had portrayed him as a “hustler” with a humble background of going barefoot and selling chickens by the roadside, a counterpoint to the political dynasties represented by Kenyatta and Odinga. His presidential flag features a wheelbarrow, the symbol of his campaign.

But he received powerful political mentoring as a young man from former President Daniel arap Moi, who oversaw a one-party state for years before Kenyans successfully pushed for multiparty elections.

Ruto now speaks of democracy, and has vowed there will be no retaliation against dissenting voices.

Odinga’s future

Odinga is setting himself up to be a prominent dissenting voice. He skipped the inauguration ceremony and said in a statement that he will soon “announce next steps as we seek to deepen and strengthen our democracy.”

Casual observers may be tempted to regard Odinga, defeated in his fifth shot at the presidency, as a sore loser. This is especially so given the Supreme Court’s dismissal of his claim that Venezuelans had hacked a 34A form to favor Ruto as “nothing more than hot air.”

However, the court ruling also said Odinga’s petition will most likely result in “far-reaching” reforms in the electoral commission. At the very least, his petitions have achieved important reforms and shifts in public attitudes. Kenyans now recognize the courts as the final arbiter of election conflicts. This is significant in a country where more than 1,000 people were killed and hundreds of thousands internally displaced in the violence after the disputed election in 2007.

Odinga has granted the judiciary the opportunity to establish and enhance its independence. His petition to the Supreme Court after the 2017 presidential election alleged significant levels of fraud. It claimed the electoral commission had failed to transmit the results electronically, as required by Kenyan law in order to minimize fraud. The Court’s ruling in 2017 emphasized that there had been problems with transmission and verification of the results.

This contributed to the reforms that were made in preparation for 2022. Thanks to his 2013 petition and related cases, the Supreme Court ruled that results counted at the polling station were final. This made it mandatory to post the results at each station for the public to view and to compare them with those on the online portal run by the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission. That helped make this year’s election more efficient and transparent than 2017’s.

During the 2022 election cycle, the Internet was not shut down, opposition leaders were not arrested, and there was no hint that the incumbent, Uhuru Kenyatta, was seeking ways to change the constitution so he could stay in power indefinitely.

These changes helped Odinga’s supporters in particular and Kenyans in general appreciate the role that peaceful resolution of election conflicts can play in deepening democratic governance. And the Kenyan judiciary has proven itself capable of exercising independent judgment and bringing finality to elections.

Time will tell what Odinga will do next, and how the former president, Kenyatta, will respond to events.

Painful economic outlook

The road ahead for the nation is a difficult one. Ruto inherits an economy saddled with debt, inflation, joblessness, and national pessimism. The International Monetary Fund has also added to his pain: It recently asked Kenya to broaden its tax base and scrap the fuel subsidy, which will challenge his efforts to fulfill the sweeping campaign promises he made to Kenya’s poor.

And immediately after taking office, Ruto scrapped subsidies on fuel, saying they were unsustainable, a move that could raise prices and lead to further inflation – something that he campaigned against.

Broadening the tax base will mean bringing more “hustlers” – Ruto’s base of informal workers – into the tax net. That could annoy his supporters.

Ruto made the economy the main focus of his campaign, promising Kenyans a radical transformation if he won. But implementing that will require money and new economic structures, and will face resistance from defenders of the status quo.

Some decisions to turn the economy around can be taken immediately, others later. One reality Ruto must face is that it takes time for most economic policy actions to make a noticeable difference.

This lag can be a political problem, more so when an election is based on great expectations and big promises. Lowering taxes on goods and services does not immediately translate into lower consumer prices, because old stocks must be sold off first. Cutting interest rates does not lead to an immediate boost in economic activity, as businesses and consumers take time to decide how much to borrow and whether to invest or consume to create demand.

Kenyans and others will be watching to see how Ruto’s economic policies and political actions will differ from those of former presidents Jomo Kenyatta, Daniel arap Moi, Mwai Kibaki, and Uhuru Kenyatta.

– Story by Gabrielle Lynch and John Mukum Mbaku with additional reports from wire services.