Finally, after years of civil war and months of deadlocked peace talks, rival South Sudanese leaders President Salva Kiir and Riek Machar are sharing power in a new peace deal. But can they manage to work out the details of governing without rupturing the fragile truce between their forces, and also make peace with smaller insurgent armies?

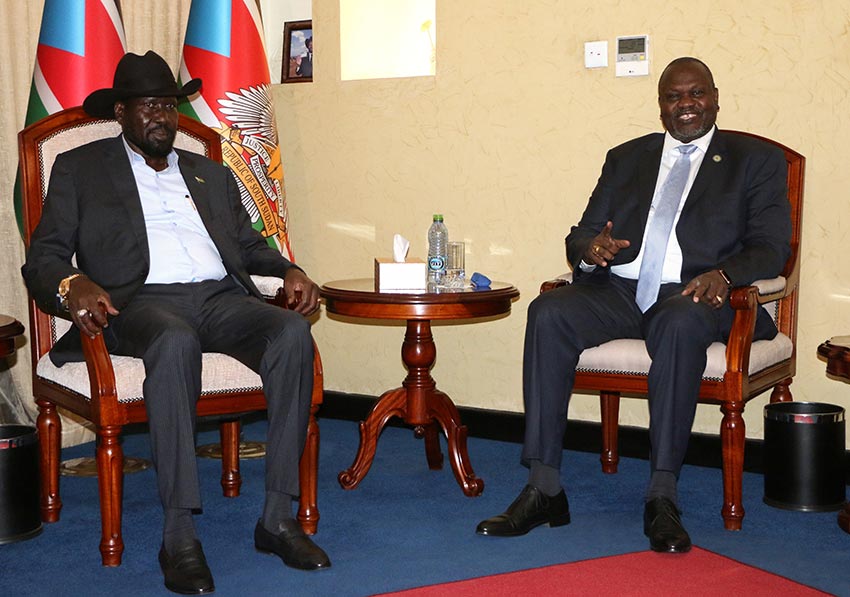

On February 22, Riek Machar and other opposition leaders were sworn in as vice-presidents in a new South Sudan unity government, part of a deal aimed at ending six years of conflict. President Salva Kiir declared the war officially over and asked for forgiveness from Machar, his longtime archrival, who in turn pledged to work in partnership with Kiir. The unity government’s formation, delayed twice over the last nine months amid political deadlock, gives the country’s leaders a chance to build upon a ceasefire between Kiir’s forces and Machar’s that has largely held for over a year.

South Sudan is hardly out of the woods, however. Kiir and Machar’s past attempts to share power have foundered. They will need to unify the national army, resolve disputes over control of key cities, and make peace with holdout rebel groups. Continued pressure from the leaders of nearby nations who played a key role in pushing them to strike a bargain will almost certainly be critical to the new arrangement’s success.

If the two main belligerents had not reached a deal by the Feb. 22 deadline they set for themselves, the fragile ceasefire, part of a peace framework laid out in their September 2018 accord, might well have started to unwind. Even a year after they stopped fighting, major towns remain in ruins, emptied of most of their inhabitants. Ghost neighborhoods stretch on and on in settlements across the country, the homes stripped of roofs and their walls caved in. As many as 400,000 people may have died in the conflict that started in December 2013, and an estimated 4 million were displaced, in a country of 12 million.

Preserving the new government’s unity will not be a small task. Kiir and Machar have been bitter political rivals almost since South Sudan became independent in 2011. Both are under pressure from hardliners in their camps to extract as much benefit as they can from the new government.

Yet there are also reasons to believe that progress is possible. The two have shown more commitment to the peace process than they did in the past. That the ceasefire held as long as it did is encouraging, as are the compromises they reached to enable the Feb. 22 swearing-in ceremony.

One major sticking point concerned the number and demarcation of states within South Sudan, which has major consequences for the distribution of power. During the war, largely in an attempt to appease demands from within his Dinka ethnic group, the country’s largest, Kiir redrew internal boundaries to expand the number of states from 10 to 28 and then 32. In order to reach the deal with Machar, he agreed to revert largely to the country’s prewar map, demarcating ten states and creating three “administrative areas,” one of them new. That required him to fire 32 governors and reverse some of his most hotly disputed gerrymandering.

To be sure, Kiir made this concession only under high-level pressure from the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), the regional bloc mediating the peace deal, and President Yoweri Museveni of neighboring Uganda, the man who by some accounts is his strongest ally. However, it broke the deadlock in the peace talks. It gave Machar the political space to return to the capital, Juba, without losing his grip on his fractious coalition, some of whose members had threatened to keep fighting if Kiir’s wartime state boundaries stayed unchanged.

Even after President Kiir’s concession on the states’ issue (bringing it back from 32 states to the original 10), South Sudan’s new peace agreement may yet collapse (again) if a serious disagreement between Kirr and Machar over the control of the states is not resolved amicably. In early May, Kiir’s office announced that it would control the leadership of 6 of the country’s 10 states, while Machar’s side would control 3 and an alliance aligned neither with Kiir nor Machar would control one. Machar objected to the sharing of the states, risking another major breakdown of the new, fragile, unity government.

“The allocation of the states,” Machar said in a statement, “is that of the president and not a decision taken by consensus. It does not take into consideration the relative prominence each party has in each of the respective states or counties.” The latest disagreement risks jeopardizing the gains made so far toward a lasting peace, as previous peace deals have held for only a matter of months before disagreements led to the resumption of war.

A second hurdle was finding a responsible answer to the sticky question of Machar’s personal security in Juba. Crisis Group had previously warned that Machar should not bring his own forces into the capital, as he did in 2016, when the two men last tried to form a unity government under the terms of an earlier peace agreement. Amid political disagreements, his forces clashed with Kiir’s, scuttling the peace deal and reigniting the war.

In the current peace talks, Machar asked Kiir to allow UN peacekeepers to provide security in Juba. Kiir refused, but regional and international pressure on Machar to compromise following Kiir’s concession on state demarcation was successful. Machar returned to Juba without his own security force, relying on Kiir’s personal guarantee for his safety, at least for the time being. It was a bold move for him, as Kiir’s forces have twice chased him out of the capital, in 2013 and 2016.

Final deal?

With those two issues out of the way, the parties were able to close the deal, even though they left other major sticking points – including how to speed up the lagging unification of troops loyal to Kiir or to Machar into a single army – to be addressed as the new government moves to cement the peace. Although the two leaders will no doubt be focused for weeks or longer on horse-trading over who should occupy government positions and influential state governorships under the peace deal’s power-sharing formula, they cannot afford to put aside these substantive matters for long.

Managing the many armed groups around the country is a particularly pressing concern. The first phase of the promised army reform meant to bring together 83,000 troops, and the process of melding the erstwhile antagonists into a single force will likely last for years. Thousands of Machar’s troops have already amassed at designated training sites near Juba and elsewhere in anticipation of unification, but they are also a reminder of how quickly peace could unravel if Kiir and Machar do not keep their competition in check. Rival rebel commanders have refused to assemble together, and both sides have embarked on new recruitment drives to expand their ranks.

The fighters will be watching closely for signs of short-term progress. In order to create momentum for unification, the forces already at joint training sites should proceed to graduation and unified deployment so that skeptics, particularly those in the opposition forces, do not lose faith in the process.

The unity government will also need to work with the new governors being installed to address long-simmering conflicts that predate this civil war, particularly over the control and governance of two war- ravaged major cities, Wau and Malakal. It will also need to reach peace deals with insurgent groups that did not sign the 2018 agreement, particularly the rebels in the southern Equatoria region led by Thomas Cirillo, and maintain the ceasefire reached with Cirillo and other holdout parties in January. Encouragingly, the government has committed to proceeding with political negotiations with these groups in the Rome peace track, mediated by the Sant’Egidio community.

A fragile unity

The regional powers that pushed Kiir and Machar to make the compromises enabling the Feb. 22 deal likewise cannot rest. The two warring leaders were still locked in their positions just two weeks before that agreement, when IGAD met in Addis Ababa on the sidelines of the African Union (AU) summit. Uganda’s Museveni, along with Sudanese Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok, reportedly pushed Kiir to return to the prewar ten-state demarcation. South African President Cyril Ramaphosa, who chairs the AU’s “C5” group of five countries mandated to support the South Sudanese peace process, conducted his own shuttle diplomacy in Addis Ababa following the months of mediation efforts by his deputy, David Mabuza, on the dispute over states. Kenyan special envoy Kalonzo Musyoka reinforced those efforts. Now, their collective attention and effort will be needed to help the unity government get on its feet and prevent any future fallout between Kiir and Machar from derailing South Sudan’s journey back from war.

Top donor countries, including the “troika” of the U.S., the U.K., and Norway, as well as the European Union and others, applied important diplomatic pressure in the run-up to the agreement. Escalating U.S. sanctions on Kiir’s government and threats to levy more on both sides added to the pressure. Continued unity of purpose among donors, in both the carrots they offer and the sticks they wield, will be key to pushing Kiir and Machar to keep their commitments to peace.

Even the Pope

Meanwhile, church leaders, both global and local, should lobby South Sudanese and regional leaders publicly and privately to keep the peace accord on track, as they did before the unity government was formed. The Vatican could have a particularly important part to play. Kiir continues to refer to his April 2019 visit to Vatican City, where Pope Francis knelt on the ground and kissed both his and his rival’s feet. He now hopes for a papal visit to South Sudan to commemorate the country’s move toward peace.

Many South Sudanese reasonably doubt that Kiir and Machar can ever work together. With elections looming in three years, and Machar planning to challenge Kiir for the presidency, their relationship will remain fraught. Still, there are grounds for some cautious optimism. Fatigued by the long war, many South Sudanese fervently wish to put the years of bloody conflict behind them once and for all. The parties have thus far avoided repeating some of the mistakes of the past, such as dividing Juba between dueling security forces.

Moreover, although it took substantial external pressure, the magnitude of the compromises Kiir and Machar have made suggest that they are now both more willing to participate in a unity government. They will now have to make a habit of the kind of concessions that made the February 22 deal possible, striking the bargains needed to keep the fragile unification process on track and to allow their young country to end the brutal war that has already gone on far too long.

— A report by International Crisis Group