Last year, thousands of Russian prison inmates were offered pardons if they served for six months in the war against Ukraine, fighting in the Wagner Group’s mercenary army. Three of those who did were Africans, from Tanzania, Zambia, and Cote d’Ivoire, who’d migrated to Russia and run afoul of its harsh drug laws. Two of them died on the battlefield, one in the bloody attempt to take the Ukrainian city of Bakhmut. Here’s an in-depth look at their stories. Giulia Paravicini, Filipp Lebedev and Felix Light report.

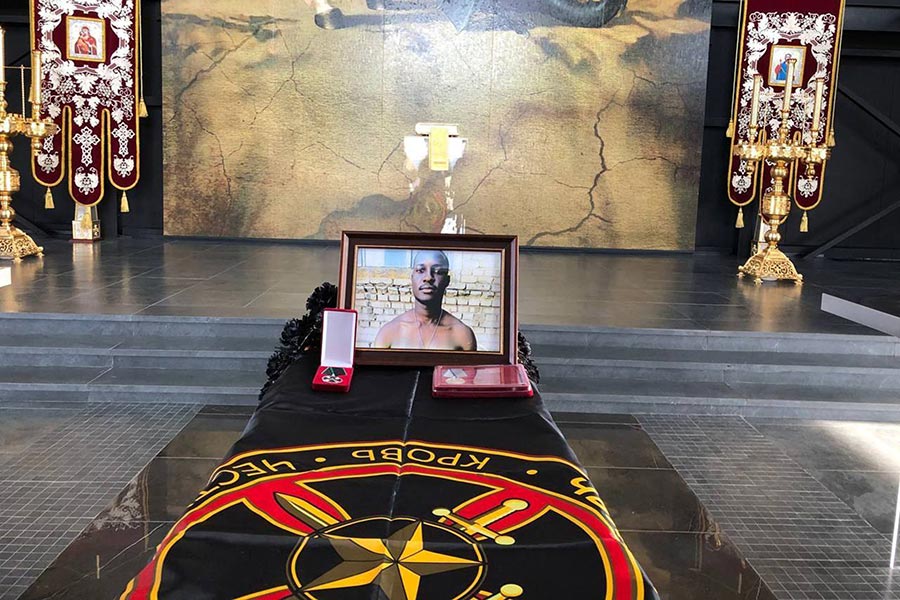

In the roll call of the thousands of Russian Wagner Group fighters killed in the ferocious battle for the Ukrainian city of Bakhmut, there is an unexpected name. Nemes Tarimo, from Dar es Salaam, Tanzania’s largest city, died on Oct. 24 last year when his unit in the Wagner private army came under artillery fire in the village of Odradivka, just south of Bakhmut. The stocky, round-faced 32-year-old was “a courageous and able fighter,” his commanding officer wrote in a report on Tarimo’s death.

Four years earlier, Tarimo had arrived in Moscow to further his education, filled with ambition, his family said. He enrolled in a Russian-language course at Moscow’s Pushkin Institute, then transferred to a postgraduate program in information technology at the city’s Russian Technological University. “Nemes had big dreams,” said his cousin, Rehema Kigobe, in an interview at the house where Tarimo grew up.

In journeying to Russia, Tarimo was following the route that many young Africans, including future heads of state, have taken since the 1960s. Starting in Soviet times, Moscow had opened its arms to African students as a way of courting influence in countries that were just shaking themselves free of Western European colonial rule. Today, some 35,000 African students are enrolled in Russian universities and colleges, the country’s education minister said earlier this year.

Tarimo also ended up treading the path of a handful of other Africans who took up arms for Wagner in Ukraine. He, a young Zambian man called Lemekani Nyirenda, and Komenan Aboya from Cote d’Ivoire all came to Russia in hope of advancement, fell into crime, and were jailed on drug convictions.

The three Africans were among the tens of thousands of Russian convicts who took up Wagner’s offer of a pardon in return for six months’ service in Ukraine. In the mercenary army’s ranks, they would serve alongside fighters mainly from Russia and former Soviet states, but also small numbers of Afghans and Arabs, some of whom may have been recruited on Wagner’s previous foreign campaigns.

Their stories tell of soaring ambitions and broken dreams. They also show the strength of the bond some young Africans feel for Russia, which is untarnished by an imperial past in a continent where it had no lasting colonies. Claire Amuhaya, a Kenyan lecturer at Moscow’s People’s Friendship University, which draws many of its students from Africa, said this bond was forged during the Cold War, when the Soviet Union backed African independence movements and supported the armed wing of South Africa’s African National Congress in its fight against white minority rule.

The connection remains to this day, even though many African countries hold far more significant trade balances with the European Union and United States, and have adopted a largely neutral stance on the war in Ukraine. In March 2022, 17 African countries, including South Africa, abstained as the United Nations General Assembly voted overwhelmingly to reprimand Russia for invading Ukraine. The presidents of South Africa and Zambia are now among a group of African leaders seeking to mediate between Russia and Ukraine.

The Wagner Group as well has cemented strong ties with several African governments over the past decade. It has operations in at least eight African nations, according to leaked U.S. documents, including Mali, Libya, and Central African Republic.

Officials in the three men’s homelands – Tanzania, Zambia, and Cote d’Ivoire – didn’t respond to questions about the individual cases and about Wagner’s recruitment of foreign nationals.

Nemes Tarino’s story

Nemes Tarimo was born into a middle-class family but orphaned at an early age. His extended family raised him in Mbezi kwa Msuguri, a suburb on the western fringes of Dar es Salaam where Tarimo inherited a house tucked alongside the main highway out of the city. His social media profiles show that before leaving for Russia he worked as an accountant for a logistics firm.

“Nemes was ambitious,” said his cousin, Rehema Kigobe. She described him as a quiet, non-confrontational person who loved computers and reading. He dreamed of moving abroad, then launching a business or political career in his homeland. “He wanted to be a big person,” she said.

In Russia, Tarimo chronicled his new life on social media, posting photographs from the seaside resort of Sochi, the skyscrapers of Moscow’s financial district, and from a cultural festival at his language institute. In December 2018, he attended an international youth conference in Moscow that was addressed by President Vladimir Putin, and appeared in a promotional video for the event. Tarimo was also pictured at several events hosted by the Tanzanian embassy, sometimes with the ambassador. Tanzanian embassy officials didn’t respond to requests for comment for this article.

In 2020, Tarimo briefly returned to Tanzania. He tried to become a parliamentary candidate for Chadema, the main center-right opposition party, but narrowly missed out on selection, party documents show. He did not stay in Tanzania long, telling relatives that his fiancée was pregnant and he wanted to return to Moscow for the birth. These writers were unable to identify Tarimo’s fiancée or child.

Family members said Tarimo had become harder to contact more recently, and that he would change phone numbers often, calling relatives using the numbers of friends in Moscow. Somewhere along the line, he slipped into crime.

He was arrested in January 2021 in a residential district in south Moscow. According to court papers, police officers reported seeing Tarimo hiding items in the snow. They said he appeared nervous, his eyes darting from side to side. The court documents said he was carrying 8.33 grams of the stimulant mephedrone, divided up into small bundles, ready for distribution.

The court handed down a sentence of seven years in a “strict regime” prison, where conditions are tougher, with fewer rights to receive visitors, correspondence, and spending money. A person who was in the courtroom said Tarimo appeared to understand little during his trial and was in a state of shock when his sentence was announced. Tarimo’s state-appointed lawyer, Alexander Shilkin, said that the term was light for a drug-dealing charge, and that prosecutors had accepted a plea for a relatively lenient sentence. “I hadn’t heard that he died,” said Shilkin. “That is very sad. He seemed to me to be a good person who committed his crime due to his difficult circumstances.”

Wagner founder Yevgeny Prigozhin and Russia Behind Bars, a prisoners’ rights watchdog group, both said Tarimo was incarcerated at Yaroslavl region’s Penal Colony No. 2 in the city of Rybinsk, 267 kilometers north of Moscow. Russian prison authorities didn’t comment.

Five foreign students who knew Tarimo during his time in Russia were interviewed. Some of the students said they worked part-time off-the-books jobs on building sites or in restaurants in order to help fund their studies. All said they were shocked that Tarimo, who they described as reserved and respectful, had become involved in drugs. Kristian Malundama, who lived in the same student hostel as Tarimo, said he first learned of the Tanzanian’s arrest from the building’s superintendent, after he vanished suddenly in January 2021. “I had trouble believing it,” said Malundama, who is from the Democratic Republic of Congo. “He was such a calm and serious boy.”

Tarimo’s relatives told Tanzanian media that he first informed them that he had been jailed in June 2022, almost 18 months after his arrest.

The death report filed by his commanding officer said the Tanzanian joined Wagner on Aug. 24, 2022. Almost 400 convicts departed with the mercenary group’s recruiters from prisons in the Yaroslavl region that day, according to the Russian independent news site MediaZona.

Prigozhin said that he had personally recruited Tarimo from prison. He quoted Tarimo as having compared the position of residents of Ukraine’s mostly Russian-speaking Donbas region, which Russia has cast as central to its war in Ukraine, to that of Africans, who he said were treated as “animals” by white people. His account could not be verified.

Tarimo last contacted his relatives last October, according to several media reports in Tanzania. He said he was going deep into the mountains to serve food to soldiers, and that he would be unreachable for some time. He promised to come back to Tanzania in January 2023, “if God wished it.”

The engineering student

Life was also filled with promise for Lemekani Nyirenda when, aged 19, he left his home in Zambia to continue his education in Russia. It was 2019. The outstanding student and devout Christian had won a Zambian government scholarship to study nuclear engineering in Moscow.

But Nyirenda didn’t complete his studies. Last November, his family learned that he too had died in Ukraine fighting for Wagner. The news came in a text message from an unknown number: “Hello, I have bad news for you. Your son took part in a military operation in Ukraine. Unfortunately [he] tragically died. Will you be able to arrive in Russia? Lemekani left a will and personal belongings for you. I am very sorry… with all my heart.” The message said nothing more about the circumstances of his death.

Nyirenda was born into a devout Baptist family in the Zambian capital Lusaka’s Northmead neighborhood, a middle-class district of large houses and tarmacked streets. His father is an engineering professor, educated in the United States and South Africa. Nyirenda attended a succession of private schools.

The family’s pastor, Ronald Kalifungwa, said that Nyirenda drifted away from his parents’ faith as a teenager, but returned to Christianity in 2018 when he was “born again.” Nyirenda’s social-media posts, showing a young man with a toothy grin and dreadlocked hair, testify to an intense interest in the politics of his homeland, and a renewed, deep Christian faith.

“Thank you Lord for seasons, thank you Lord for summer,” he wrote on Instagram in June 2020, at the height of the COVID pandemic, accompanied by photographs of himself and an unidentified friend in Moscow, posing for the camera dressed in their summer clothes and smiling widely. “Took a walk with the guys today. It was therapeutic on so many levels. Number one recommend y’all to make time for walks in the evening.”

Relatives described Nyirenda as “a family-oriented person” with a sense of fun – invariably introducing his mother to friends as “Queen Mother.” He excelled academically. In 2019, after a year at a Christian college in Zambia, he and his twin brother, Zikonde, won government scholarships to study abroad – Zikonde in China and Lemekani in Russia.

Enrolling at Moscow’s National Research Nuclear University in September 2019, Nyirenda launched a YouTube account, where he uploaded whimsical videos about his life in Russia, his homesickness, and telling Bible stories, often from the modest student dormitory bedroom that he shared with two others. Several people who knew Nyirenda said that he missed his hometown Baptist church, and had difficulty finding a congregation to join in Russia.

In the months that followed, Nyirenda too became involved in the drug trade. In a May 2020 YouTube video, he said that his financial situation had improved, and that he was learning to manage his money better. “I’m not a broke, struggling student any more. I’m just a broke student,” he said. He was arrested that August.

According to court documents, Nyirenda told investigators that he had posted an ad online looking for work, and had received a call offering him a gig transporting small bundles around Moscow. He was to hide the bundles at set locations. In return, he received 200 rubles ($2.40) per bundle, according to the court papers.

A ‘model prisoner’

A person who was present at Nyirenda’s trial said that the Zambian took his nine-and-a-half-year prison sentence stoically and was “generally positive.” The person said that Nyirenda’s Russian was good, and that he needed little help understanding the proceedings. An online system for contacting Russian prisoners showed that Nyirenda served his sentence in the Tver region’s “strict regime” Penal Colony No. 1, 180 kilometers northwest of Moscow. Prison authorities didn’t comment.

Nyirenda’s family and friends said that he was a model prisoner during his spell behind bars. Family friend Christopher Kangwa said that after his arrest, Nyirenda asked the Zambian embassy in Moscow to forward him his Bible and toiletries bag. Nyirenda’s older sister Tionge said in a eulogy at his funeral that during his two years as an inmate, he read all the books in the prison library, learned fluent Russian, and taught himself to sew. She said he had proudly showed her his hand-stitched prison uniform during a video call, a rare privilege for Russian prisoners, which she said prison authorities allowed him as a reward for his good behavior.

During her eulogy, which was streamed online, Tionge also said that her brother had told her during their last video call that incarceration had revealed a hitherto unknown inner strength. “He told me and my husband how he didn’t know that he was so strong,” said Tionge, dressed in mourning black from head to toe. “The whole imprisonment experience had shown him how strong he was.”

Nyirenda last spoke to his family on Aug. 31, 2022, according to the pastor, Kalifungwa. Kangwa, the family friend, said that he sounded “in a hurry and under pressure.” He said he hoped that they would soon be reunited, and implied that he had been released from jail. He said he could not say where he was, and asked his father for details to designate him as his next of kin. His last word to his family was “musalebwino,” meaning “farewell” in the Nyanja language, spoken in the family’s ancestral homeland in eastern Zambia. “We believe that this was the time Wagner had taken him and commissioned him in the war,” Kangwa said.

There is no confirmation when Wagner recruiters visited Tver’s Penal Colony No. 1, but Prigozhin was visiting nearby prisons throughout the summer of 2022. He said in a Nov. 29 statement via his press service that he personally recruited Nyirenda. He said that, like Tarimo, Nyirenda cast his desire to join Wagner as repayment for Soviet and Russian support of African anticolonial movements. According to Prigozhin, Nyirenda told him that joining up was “the least I can do to pay [these] debts” to Russia and that he had heard that Wagner had saved “thousands of Africans.”

The Ivoirian entrepreneur

On Jan. 1, Russia’s state-owned RIA news agency published a video from the outskirts of Bakhmut, showing Prigozhin laughing and joking with another African fighter he identified as an Ivoirian national. In the clip, the fighter says, in heavily accented but fluent Russian, that he joined up “to defend my second Motherland.” The Wagner boss said he had told the fighter that he would hire him as a French interpreter, if he survived his six months at the front.

In a Jan. 4 comment via his press service, Prigozhin identified the fighter as Komenan Aboya, a convicted drug dealer. In a separate statement, he said he recruited Aboya from jail in Mordovia, a region near the Volga River known for its harsh prisons.

Aboya’s friends in Cote d’Ivoire described him as an entrepreneurial man, now aged about 40, who yearned to be financially independent. He grew up in Yopougon, a poor and overcrowded neighborhood in Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire’s largest city. There, on streets teeming with bars, he opened a small video club, where he would show action movies, said a one-time regular called Fabrice.

Each morning, Aboya would rise early, and get in line to secure a seat in one of the hundreds of crammed gbakas, the minibuses which line Yopougon’s dusty thoroughfares, in order to reach the plush suburb of Cocody, where he worked as a bus driver.

Former colleagues said that in 2015 or 2016, Aboya took out a bank loan and moved to Russia, where he began driving taxis. One colleague said he decided to leave for Russia to give his two children a better life than his own. A person who knew Aboya in Moscow said the Ivoirian and other African residents of the city would often gamble when they met up, placing small bets on games of chance.

According to court papers, in July 2018 he was sentenced to eight and a half years in prison for drug-dealing. A video published online the previous August by Moscow police shows the arrest of an unnamed West African man. Facial-recognition technology indicates that the man in the video is Aboya. Russian media reported the suspect was carrying around 100 grams of cannabis. In the video, he tells officers, in broken Russian, that the drugs are not his and that he is waiting for a friend.

Of the three African men who risked everything to get out of prison early, only Aboya survived to claim his reward.

Nyirenda was killed on Sept. 22, 2022, while storming a Ukrainian trench, barely three weeks after he last spoke to his family. “He died a hero,” said Prigozhin. He was 22. A month later, Tarimo too was dead.

In a brief statement on April 5, Prigozhin confirmed that Aboya was alive, had completed his six months’ service in Ukraine, and that his conviction for drug-dealing had been expunged.

“Yes, Komenan Aboya fought in the ranks” of Wagner, he said. “He was pardoned at the end of March, and is currently undergoing a rehabilitation course. He fought bravely.”

Prigozhin would be dead a few months later. He and nine others were killed when their small plane exploded in midair between Moscow and St. Petersburg on Aug. 23, two months after he led a mutiny against Putin.